The art of the revolutionary and early Soviet era in Russia has a unique ability to inspire fetishism. Its radical allure, combined with the revolution’s short-lived unleashing of avant-garde aesthetics, has made posters and other forms of mass-produced visual art from that period a staple of book covers, museum exhibitions and living rooms. Yet the circumstances in which this art was made are much less familiar. We may know individual artists or collectives, but it’s rare for someone to hang a poster on their wall knowing when and how it was commissioned and who, if anyone, made any money in the process.

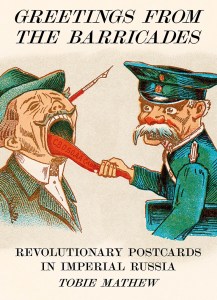

The journalist and historian Tobie Mathew has written a much more substantive and original treatment of the subject. Greetings from the Barricades departs from the typical approach in three important and unexpected ways. First, he focuses on the aftermath of the Revolution of 1905, which erupted amid labour unrest as the Russian Empire was losing a war with Japan. Labelled a ‘dress rehearsal’ by Lenin, this abortive experiment – to which the tsar responded by creating a restricted parliament and some limited civil rights, but also with a wave of repression – is usually treated as a mere speed bump on the way to 1917, but Mathew shows its importance for building a revolutionary mass culture. Hence his second innovation: he focuses on the small-scale genre of postcards (most of them from his personal collection), whether actually mailed or passed hand-to-hand, rather than the more public newspapers and billboards. (This is not the first English-language study of Imperial Russian postcards in this era, though works like Alison Rowley’s Open Letters of 2013 are not as focused on politics.) Finally, although he devotes plenty of time to aesthetics, he takes a materialist approach: what primarily interests him is the economic and legal structure within which the postcard trade developed and which made them items of mass consumption alongside cigarettes and tabloids. Even frequent arrests of anti-government artists, publishers, and distributors did not sate the public’s appetite for these cheap and convenient visual objects, colourful or sombre reminders of the political situation in the empire.

The journalist and historian Tobie Mathew has written a much more substantive and original treatment of the subject. Greetings from the Barricades departs from the typical approach in three important and unexpected ways. First, he focuses on the aftermath of the Revolution of 1905, which erupted amid labour unrest as the Russian Empire was losing a war with Japan. Labelled a ‘dress rehearsal’ by Lenin, this abortive experiment – to which the tsar responded by creating a restricted parliament and some limited civil rights, but also with a wave of repression – is usually treated as a mere speed bump on the way to 1917, but Mathew shows its importance for building a revolutionary mass culture. Hence his second innovation: he focuses on the small-scale genre of postcards (most of them from his personal collection), whether actually mailed or passed hand-to-hand, rather than the more public newspapers and billboards. (This is not the first English-language study of Imperial Russian postcards in this era, though works like Alison Rowley’s Open Letters of 2013 are not as focused on politics.) Finally, although he devotes plenty of time to aesthetics, he takes a materialist approach: what primarily interests him is the economic and legal structure within which the postcard trade developed and which made them items of mass consumption alongside cigarettes and tabloids. Even frequent arrests of anti-government artists, publishers, and distributors did not sate the public’s appetite for these cheap and convenient visual objects, colourful or sombre reminders of the political situation in the empire.

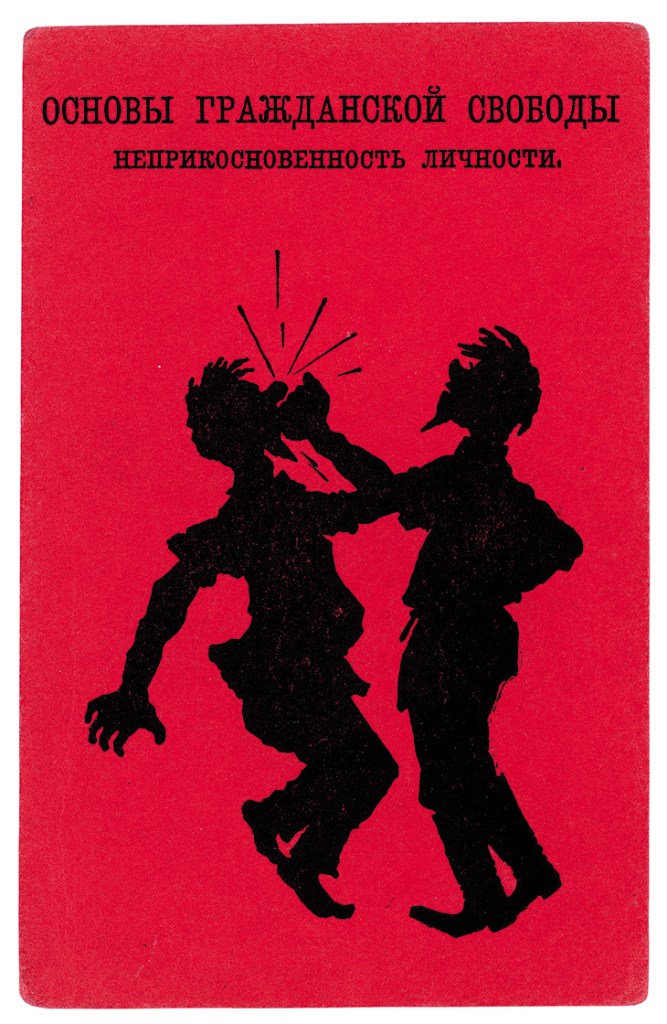

The Principles of Civil Freedom (9 November 1905), Vasil Guak, printed by I.N. Kushnerev in Moscow

Mathew’s vein turns out to be richer than even a specialist would expect. Postcards became popular at the end of the 19th century, at first as a non-political genre, depicting anodyne landscapes, modernist pseudo-folk art, religious imagery and pornography; they appealed to consumers who wanted to mark their travels or simply send an informal note, as well as to less literate buyers who were more interested in the images they contained.

The explosion of postcards as a popular art form, and hence a propaganda medium, caught the two main left-wing parties at a critical moment in their emergence, when unionising workers and peasants angry about exploitation in the countryside were making radical politics a reality on the Russian street. Both the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (which already contained a Bolshevik and a Menshevik faction but was not yet formally divided) and the Socialist Revolutionary Party soon tried their hand at making their own cards. Bucking the stereotype of their ideological rigidity, the Social Democrats were able to adapt by farming out their postcard trade to an independent leftist named Mikhail Chemodanov, who made them plenty of money but had little regard for the party line. The more ascetic and terror-oriented Socialist Revolutionaries were less successful. They neglected to improve their quality and marketing, missing out on a major source of profit and public agitation. Though postcards were not a dominant source of income for the parties, they helped underwrite their publishing ventures and build the networks that supplied literature to their reading groups.

Don’t Spare the Bullets (caricature of Dmitrii Trepov; c. 1905), unknown artist

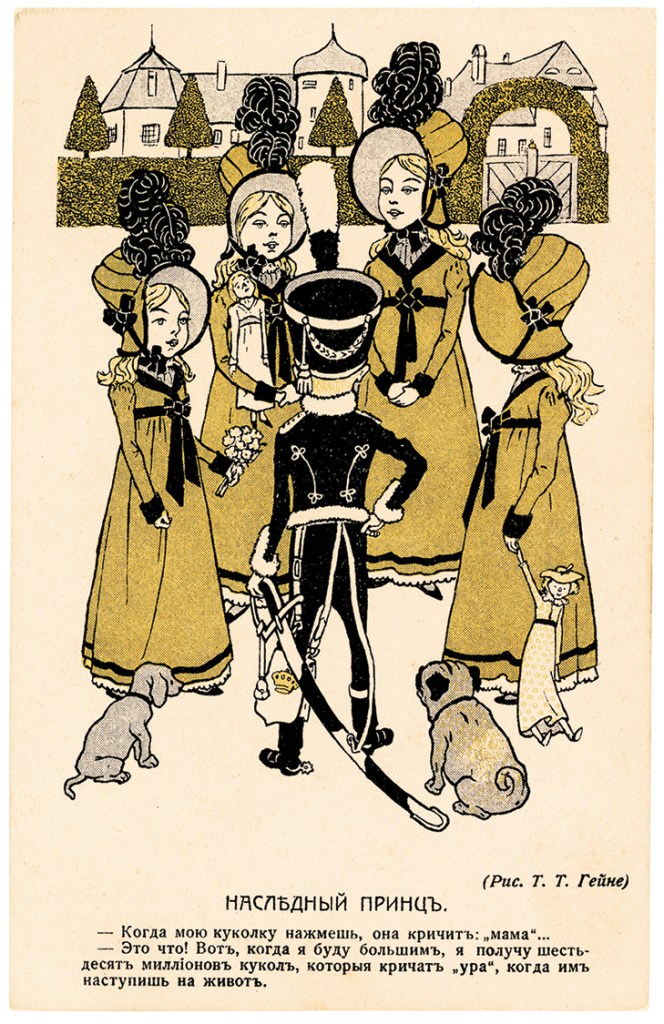

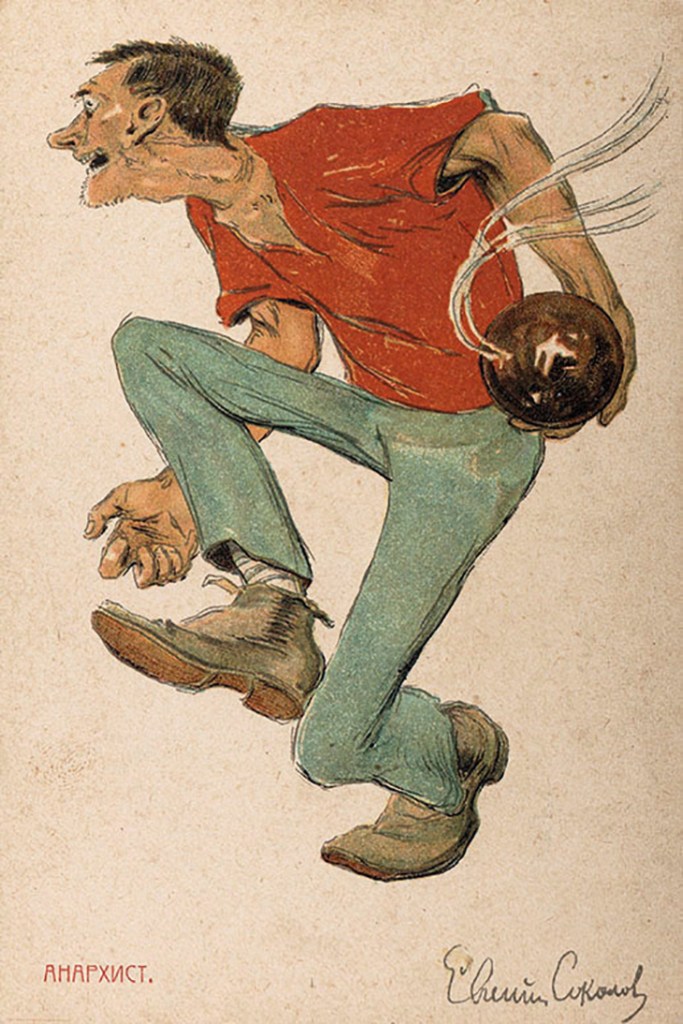

But the widespread interest in postcards wasn’t confined to formal political organisations. In the midst of a flailing (though only partly abolished) tsarist censorship apparatus, a diverse range of artists fed a growing appetite for left-wing politics. Mathew discusses the emergence of Shipovnik (‘Wild Rose’), a non-party-affiliated publishing project ‘to pursue two strands of life – socialism and beauty’. Shipovnik’s postcards were printed in colour on high-quality paper, offering a leftist aesthetic to a more discriminating customer. Other independent postcards spread graphic images of the Bloody Sunday massacre in January 1905 and, after the revolution, reflected public disappointment in the limits of the parliamentary reforms, sometimes as whimsically as Valerii Karrik’s children’s book illustrations of the Duma as bloodthirsty crocodile. As terrorism led by the Socialist Revolutionary Combat Organisation spread throughout the cities of the empire, postcards helped to glorify the terrorists and make them objects of collective veneration. On the whole, their success as an item of daily consumption contributed to the erosion of legitimacy that undermined the late imperial state.

The Crown Prince (May 1906), Thomas Theodor Heine, published by Shipovnik and printed by Golike and Vilborg, Saint Petersburg

Two postcards can illustrate the range of visual and ideological styles this bountiful genre could contain, and the ambiguities of its reception. One, a black-and-white reproduction of Moisei Maimon’s painting Back Home (1906), shows a soldier returning to his shtetl from the Russo-Japanese War and finding his family murdered in a pogrom. In Mathew’s collection, it bears a cheery note on the back congratulating a woman (evidently an Orthodox Christian) on her upcoming name day. Another, by an anonymous artist (illustrated on the book’s cover), is called Freedom of Speech; published in 1905, it is a cartoon depicting a government censor holding a writer by the tongue. It was collected by a politically non-aligned medical student and inserted into an album along with hundreds of other political postcards. Though Russians were more mobilised than ever, not every consumer of postcards saw them in terms of their political goals.

Printed in full colour in a large format that shows off the lush detail of these fragile artefacts, Greetings from the Barricades does full justice to the material. Less successful is the sometimes workmanlike prose that accompanies the visuals; Mathew has a tendency to labour the point, when a picture would (and usually does) suffice. Yet the scholarly rigour is generally quite welcome, even if the precise details of party organisation in 1907 are likely to interest only a dedicated scholarly audience or perhaps a would-be revolutionary postcard publisher. This is not a coffee-table book that strips the images of their context.

Anarchist (c. April 1906), Evgenii Sokolov, printed by E. Kudinova and A. Lezina, St Petersburg

Greetings from the Barricades: Revolutionary Postcards in Imperial Russia by Tobie Mathew is published by Four Corners Books.

From the April 2019 issue of Apollo. Preview the current issue and subscribe here.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Suzanne Valadon’s shifting gaze