In 1987, the artist Roger Ackling and his wife Sylvia bought a coastguard cottage in the Norfolk village of Weybourne – ‘a house perched on the edge of existence, cliff-hanging’, wrote Sylvia in a 1997 essay about Ackling’s work, now republished in the catalogue accompanying this exhibition at Norwich’s Castle Museum. Ackling had a predilection for confronting the edges of things and Weybourne ‘set the existential boundaries for much of what he makes’, wrote Sylvia.

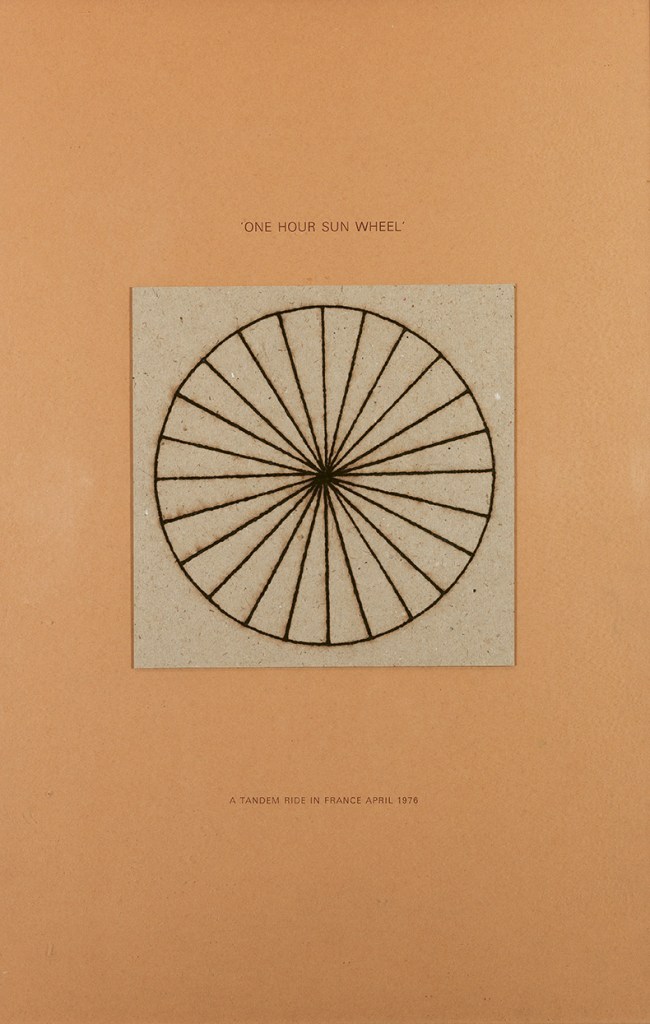

While studying at Saint Martin’s School of Art in the late 1960s, Ackling spent his summers on the Isle of Wight, where his parents ran a hotel. It was there that he began to experiment with the sun, singeing the hotel lawn with a magnifying glass. It was the beginning of a lifelong relationship with light. ‘Sunlight’ presents some 150 works in a loose chronological order, marking the subtle changes within Ackling’s practice. It includes early works such as Leaf (1974), created by using the sun’s rays to render figurative outlines on card or wood, and the meditative Cloud Arc (1979), for which he sat holding his magnifying glass over card, allowing the singed line to fade in and out as clouds passed over the sun.

One Hour Sun Wheel (1976), Roger Ackling. Courtesy Annely Juda Fine Art; © estate of the artist

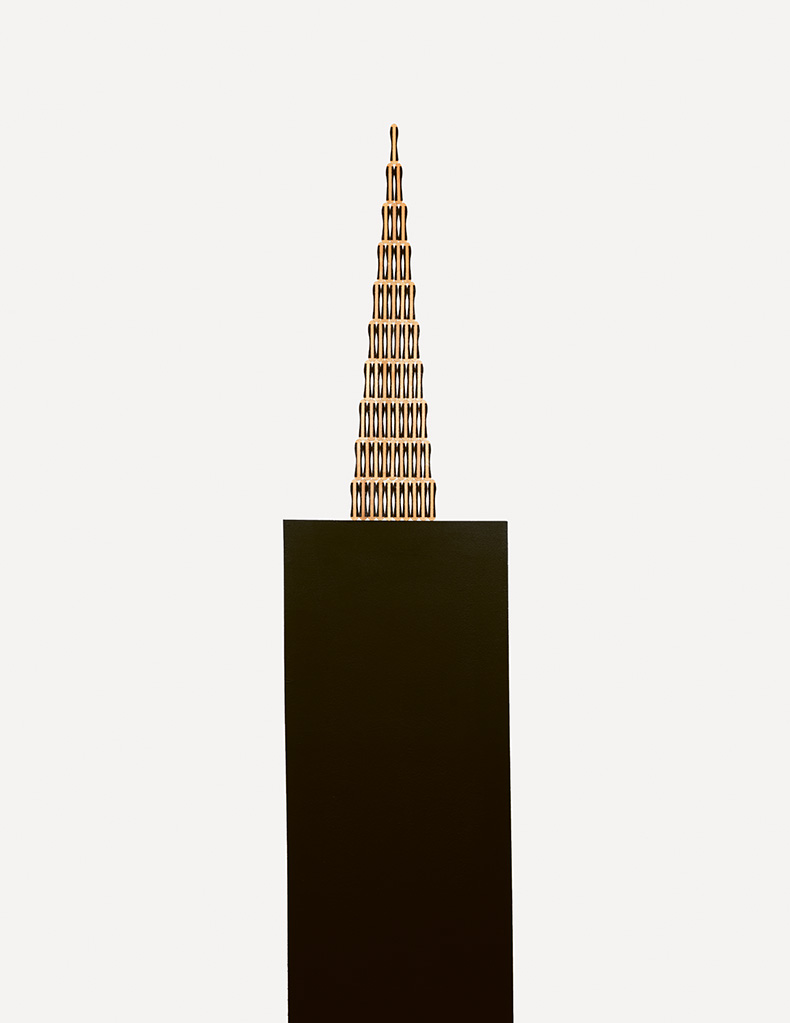

It was at Weybourne, in the late 1980s, that Ackling began to apply his marks to driftwood found on the beach, which offered not a clean canvas but a rough weather-beaten surface. He scored his cindered lines around, or in response to, wedged-in pebbles, tarred corners and flecks of paint: the marks of a past life. In Sylvia’s essay ‘Lines of Latitude’, she returns to the perils of living so close to the edge: ‘The sea eats away at the base of the cliff, sucking at its foundations with every high tide. It’s relentless.’ Ackling responded by taking what was elemental – the product of the sun and the waves – and using them to create something if not permanent, then at least enduring.

From Weybourne, the couple moved to Voewood, a little inland. Although Ackling had a studio for storing artwork and materials, the actual work was done outdoors: he would spend long hours burning lines left to right on wood or card, with the sun at his shoulder, concentrating on the thing at hand. Thingness is central to Ackling’s work. In response to a scarcity of driftwood on the beaches of Norfolk, Ackling turned to other found objects. At Voewood, a local shopkeeper gave him boxes of ice lolly sticks and wooden forks which he, forever led by materials, scored with his magnifying glass. This act reaffirmed not only his love of using what was to hand, but also for using things that could fit into your pocket. Five Doubles, Voewood (1999), its materials listed poetically as ‘sunlight on lolly sticks’, is perhaps the most playful moment in the show: a mischievous conceit in which Ackling scorched the stick with sunlight as if the ice lolly had not just melted away, but entirely vanished.

Voewood 2011–2012 (2011–12), Roger Ackling. Courtesy Annely Juda Fine Art; © estate of the artist

His artistic practice was sustained, and perhaps also nurtured, by teaching: first at Wimbledon School of Art and the London College of Furniture, and later at institutions including the Slade, Norwich University of the Arts and Chelsea College of Arts, where he taught from 1979 until 2011. His desire to teach was also a desire to be in the world. He became deeply interested in Japanese culture, which is evident in the clean lines and monochromatic palette of his work, and with the notion of wabi-sabi, in its embrace of impermanence and imperfection.

Ackling’s preference for the edges of things extended to the art world, where he existed in relation to – but not contained within – its various factions and movements. The work in ‘Sunlight’ draws from conceptual art, minimalism, land art and process art but defies easy categorisation. He bucked the conventions of minimalism by using organic matter and found materials, and the monumental scale of land art by working with pocket-sized objects. Sylvia’s essay reminds us that ‘what is often so difficult is to accept or come to terms with visual experience in its own right’. This is perhaps where Ackling’s work converges with minimalism, with Frank Stella’s assertion that ‘what you see is what you see’.

55 Units, Voewood (1999), Roger Ackling. Courtesy Annely Juda Fine Art; © estate of the artist

Ten years have passed since Ackling’s death, which allows Sylvia’s words to be read as a clear-sighted elegy to the man she loved. One line in particular resonates with Ackling’s life and work: ‘a present very solid existence and the certainty that it will soon disappear.’ The ritual-like routine of his practice, and the resemblance of his sculptures to religious votives, speaks to a certain spirituality. Ackling worked with what was close at hand to express aspects of human existence that were further away or harder to identify. In doing so, he reminds us that to be at the edge of things – even knowledge – is not to be outside them, but to approach them on one’s own terms.

‘Sunlight: Roger Ackling’ is at Norwich Castle Museum & Art Gallery until 22 September.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

When the Nazis pilloried modern art