From the June 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

In 1925, the year this magazine first appeared, Amédée Ozenfant painted a picture called Le Pot blanc. Like other of Ozenfant’s pictures of that year – Vase, say, or Three Vases – it was not a memorable work. It is unlikely that you will have seen it, or be able to call it to mind. Le Pot blanc was given to Strasbourg’s Musée d’art moderne 60 years ago. It has spent the last 40 of those years in storage.

To the victor, the spoils. Also painted in 1925 were Picasso’s Three Dancers and Kandinsky’s Trois éléments, both of which you will have seen, if only in reproduction. The Picasso is in Tate Modern; Kandinsky’s painting, like Ozenfant’s, is in Strasbourg, where, unlike Le Pot blanc, it is always on show. Yet when these works were painted, their makers were as famous as each other. The century of Apollo’s existence has treated them very differently. As the art historian John Golding was to write, ‘Perhaps no other artist of comparable stature has undergone such an almost total eclipse as Ozenfant.’

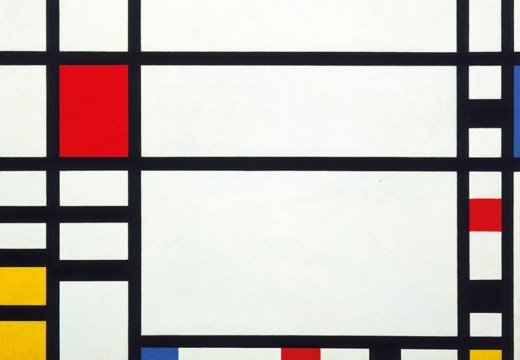

Why? Let us look again at 1925. The likeness between the three works painted by Ozenfant that year is remarkable. Each is composed in paraline perspective, its subjects being pushed flat against the picture plane like pieces in a jigsaw. Their brown-on-brown palette is the same, as are the objects – carafes, guitars, jugs – it is used to depict. Ozenfant described them as ‘object types’, things so ancient in their form and use that they had ceased to have an individual existence and become cyphers of themselves. Together, these traits would make up a style called Purism, a term coined by Ozenfant around 1916 in his magazine, L’Élan.

Le Pot blanc (1925), Amédée Ozenfant. Musée d’art moderne et contemporain de la Ville de Strasbourg. Photo: © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2025

Its watchword was restraint. Where Surrealism was subjective and individualist, Purism set out to be the opposite. Purists could only paint certain things, in certain colours and a certain way. Part of the thinking behind this was that an art that shunned difference would lead to a world free of war. But there was another logic. Ozenfant was car mad: in 1911, he had designed the Hispano Ozenfant, built for him by the celebrated Spanish auto makers Hispano Suiza. By far the most famous car manufacturer by 1916 was Henry Ford, and Ozenfant took Ford’s embracing of mass production and assembly lines to heart. Because of these, automobiles were no longer the playthings of the rich. What was needed was an equivalent in painting – not difference but sameness, prefabricated elements that could be bolted together in a standardised palette. Purist canvases would be the Model T Fords of art.

In Ozenfant’s imagining, a small number of artists, including himself, would produce object-type paintings – works so inevitable, so pure, that, like carafes and jugs, they could act as templates for infinite reproduction. These would not be ersatz but real, painted by a cadre of Purist-trained craftsmen who would work as a human assembly line. Le Pot blanc would engender a thousand more Pots blancs, or five thousand, or ten. Each would be bought by a grateful petit bourgeois whose life would be infinitely enriched by it.

The idea did not catch on. Artists including Picasso and Juan Gris absorbed the aesthetic lessons of Purism and moved on. Perhaps the purest Purist was Ozenfant’s friend Fernand Léger, although one has to look hard to see the influence.

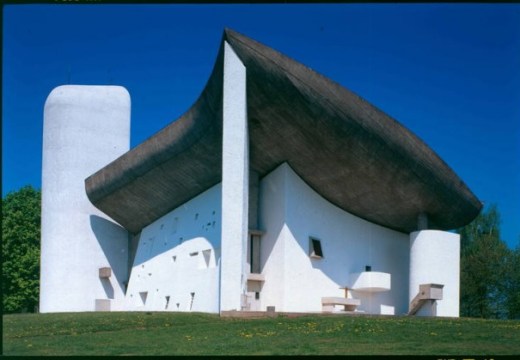

As to the philosophy of Purism, it too was a victim of its moral uprightness. This demanded that output be shared, and Ozenfant had shared his with a young Swiss architect called Charles-Édouard Jeanneret. Their 1920 essay, Le purisme, was jointly signed, although in Jeanneret’s case with the nom de plume newly invented by his mentor: Le Corbusier. In 1925, the pair fell out. It was the end of Purism; if you Google it now, it is described as Le Corbusier’s invention. History is capricious and seldom fair.

From the June 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Apollo at 100