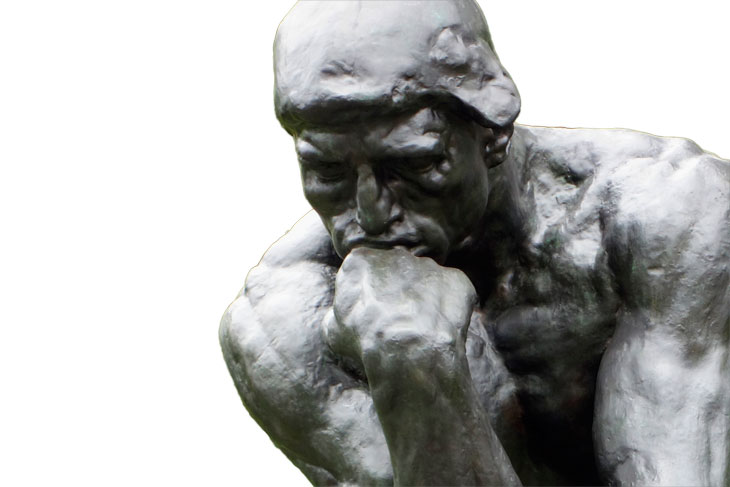

Only a handful of sculptures are sufficiently famous to achieve the dubious honour of reproduction on T-shirts and fridge magnets. Michelangelo’s David probably leads this pack but close behind must be Auguste Rodin’s The Thinker. Much parodied – the pose seems to invite mocking emulation – the work will feature this month in an exhibition in Paris’ Grand Palais which marks the 100th anniversary of the sculptor’s death (22 March–31 July).

The show is sure to be popular: the Musée Rodin, which reopened in November 2015 after a three-year, €16 million restoration, attracts over 700,000 visitors annually. During spring 1970 large numbers came to see a similarly substantial exhibition held at London’s Hayward Gallery, discussed by Jeffery Daniels in that year’s March issue of Apollo. Daniels began by noting that Rodin did not win recognition easily: he was already 36 when his life-size figure The Age of Bronze was accepted by the Paris Salon. Even then accusations were made that it had not been sculpted but cast from a living figure. The charge, wrote Daniels, ‘was a foretaste of the hostile criticism that was to greet most of his work, and which at first caused him much distress.’

As is so often the case, in retrospect, it seems hard to understand what could have caused the fuss. However, as Daniels elucidated, throughout his career Rodin appears to have attracted commissions and controversy in equal measure. In 1884, for example, the municipal corporation of Calais invited him to create a piece commemorating an incident in 1346 when, during the Hundred Years War, six burghers were required to submit to England’s Edward III in order to lift a siege on the city. Rodin’s response, insufficiently heroic for popular taste, failed to win widespread approval and, Daniels wrote, ‘it took over ten years to get the monument erected, but not where the sculptor wanted it, nor in a form that he approved: that took another thirty years.’

A similar response met Rodin’s monument to the novelist Honoré de Balzac, which was commissioned in 1891 by the Société des Gens de Lettres. When a full-size plaster model was displayed in 1898, the reaction was so hostile that the Société pusillanimously rejected it. Rodin took the work back and only in 1939, 22 years after his death, was the first bronze cast produced and placed on the Boulevard du Montparnasse. What might have been irreversible setbacks for anyone else only enhanced Rodin’s reputation as the leading sculptor of the age, a position firmly cemented when he was granted his own pavilion at the 1900 World Fair in Paris. Here a plaster cast of his monumental Gates of Hell, in which the original of The Thinker features prominently, occupied pride of place, attracting the same kind of visitor numbers as Rodin’s museum in the Hôtel Biron does now. ‘He is by far the greatest poet in France,’ Oscar Wilde wrote from Paris to Robert Ross, ‘and has, as I was glad to tell myself, completely outshone Victor Hugo.’

The reason for Rodin’s popularity, Daniels discerned, was that despite the trappings of modernity his work is rooted in tradition. The pose of the figure in The Age of Bronze, for instance, ‘is clearly derived from that of Michelangelo’s Dying Captive in the Louvre. Michelangelo was but one of the many sources from which Rodin drew inspiration, such as Puget, the French Rococo sculptors and of course the Antique; but Michelangelo as both painter and sculptor, remained the most fruitful stimulus, and references to his work recur throughout Rodin’s oeuvre.’ Daniels went on to draw parallels between Michelangelo’s immense but never completed tomb of Pope Julius II and Rodin’s Gates of Hell, a natural comparison since he had already noted how a figure intended for the papal monument served as inspiration for The Age of Bronze. Nevertheless, despite an indebtedness to the Renaissance, ‘In both his life and his work, Rodin was a Romantic, and in his devotion to grandiose projects, he recalls the archetype, Berlioz.’

One might also draw parallels with Picasso: both men shared an ability to find, and mesh together, stimulus from seemingly disparate sources, all the while never forgetting ancient classicism but refusing to become its vassal. The mark of genius in an artist is the facility to absorb and harmonise varied ideas before presenting the outcome in a fresh manner. As Daniels observed, such was the case with Rodin, whose skill lay in ‘looking back towards Michelangelo, and at the same time bringing about a re-birth of sculpture through his own work and its widespread impact’.

From the March 2017 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Is the Stirling Prize suffering from a case of tunnel vision?