From the June 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

The cover of the first copy of this magazine carried the divine profile of the marble sculpture known as the Apollo Belvedere, a fitting motif for a mag that (at the time) covered both art and music. Question Apollo’s musical supremacy at your peril – Marsyas paid for such hubris with his skin. Considered the epitome of male beauty, the god inspired the earliest nudes in Greek art. Sculptures of Apollo from the early fifth century BC mark the emergence of a physical ideal that would endure for thousands of years: a carapace of muscle cladding the torso that transitions into the legs through deep iliac furrows.

The physical perfection of Apollo was mathematic in expression, marking him out as a divine being in human form. In the 18th century, the Apollo Belvedere was considered one of the greatest works in human history, caressed by the velvet prose of the art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann: ‘In gazing upon this masterpiece of art, I forget all else, and I myself adopt an elevated stance, in order to be worthy of gazing upon it. My chest seems to expand with veneration and to heave like those I have seen swollen as if by the spirit of prophecy…’ Thanks to this status, the Apollo Belvedere was looted from the Vatican Museum by Napoleon and installed in the Louvre, where it remained for 17 years. Until the early 20th century, it topped the list of plaster casts required for study of the figure at art schools and museums.

By the mid 20th century, the Apollo Belvedere had fallen from favour. In The Nude (1956), Kenneth Clark reminded readers that this supposed masterpiece was a Roman copy in marble after a lost Greek bronze, pointing out its ‘weak structure’ and ‘slack surface’. Not for Clark these Roman cover versions – in his view everything had gone downhill since Praxiteles carved his Aphrodite at Cnidos in the fourth century BC. ‘The drift of all popular art is towards the lowest common denominator,’ Clark lamented, ‘and there are more women whose bodies look like a potato than like the Cnidian Venus.’ As to whether there are more men whose bodies look like a potato than like a Praxiteles Apollo, the great art historian declines to comment.

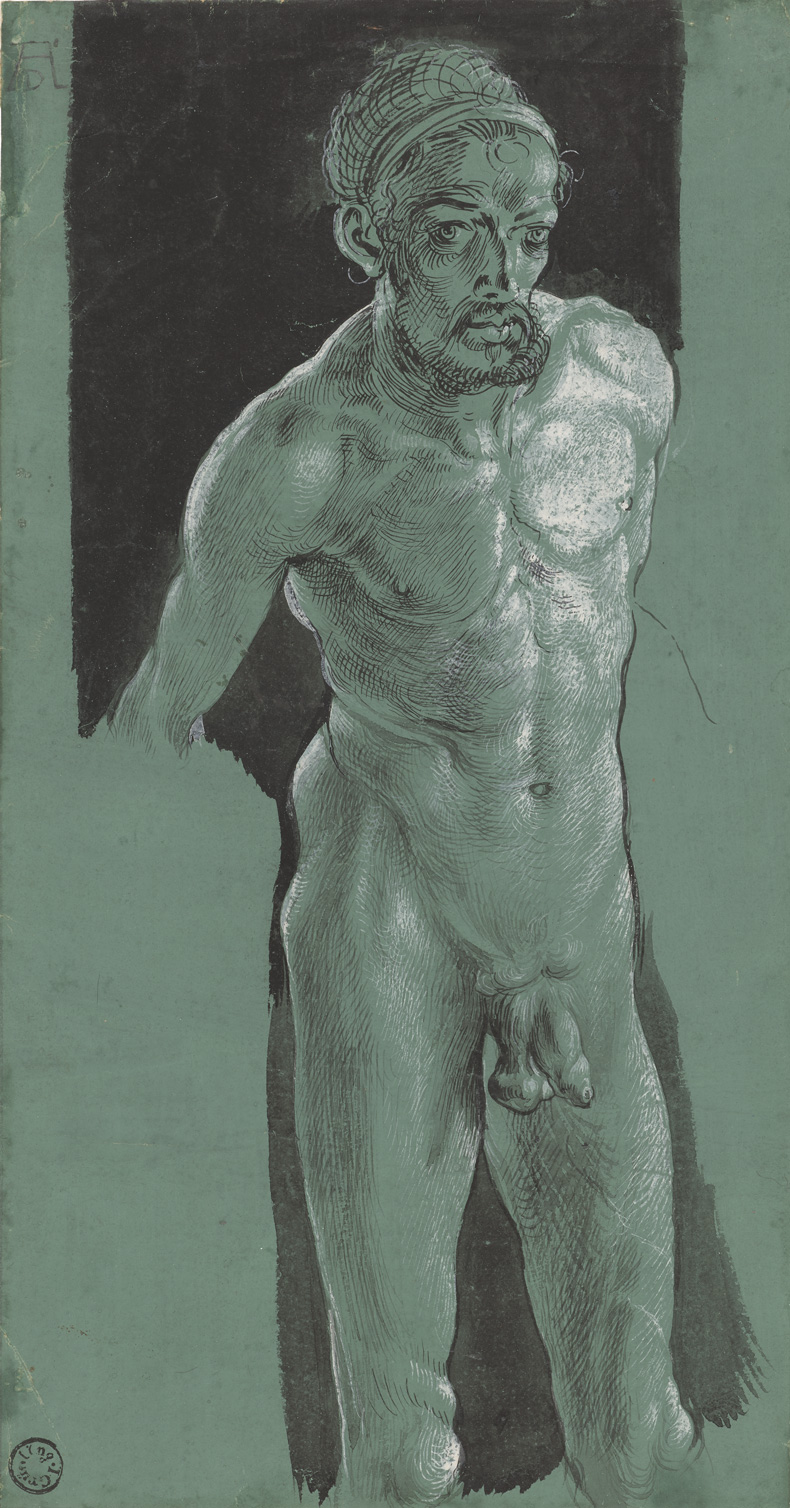

Nude Self-Portrait (c. 1509), Albrecht Dürer. Klassik Stiftung Weimar. Photo: © Klassik Stiftung Weimar, Museen

The tuberous-bodied of this world are often naked in art, rather than nude, appearing as individuals, rather than ideals. We, the potato people, have bodies that are particular. Mortal, our conformation does not abide by the supposedly divine geometry of canonical proportions. For artists, scrutiny of the body in the mirror can reveal the fascinating vegetable truth. Albrecht Dürer first used a mirror (then a rare and precious device) to draw a self-portrait in 1484, when he was 13. Twenty-five years later he stared at his reflection with rather more intense scrutiny while drawing himself naked. Dürer thought deeply (and restlessly) about aesthetics, classical proportions and the idea that beauty might abide by fixed parameters.

While his Four Books on Human Proportion (1528) provided schemata for different body types, he rejected the idea that beauty could be achieved through a formula: it had to be drawn from life: ‘Without true knowledge, who will give us a reliable standard? I believe there is no one alive capable of perceiving the ultimate ideal of beauty embodied in the least of living creatures, let alone in a human being.’ Dürer does not look unpleased with the naked figure gazing back at him from the mirror. He’s a handsome, muscular man in his late 30s. He observes, intently, the impact of gravity on his genitals, and is unsparing of his lumpy love-handle and wayward knees.

This was a necessarily private work, but in drawing his potato self, Dürer was, in so many words, escaping the tyranny of Apollo. He portrayed his curious body as it was revealed to him through observation.

Self-Portrait as a Tahitian (1934), Amrita Sher-Gil. Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi. Courtesy the Estate of Amrita Sher-Gil

When Amrita Sher-Gil (1913–41) painted her mirror image more than four centuries later, she too was performing defiance, both social and aesthetic. In Self-Portrait as a Tahitian (1934) she stands stripped to the hips, her lower body wrapped in a length of cloth. Sher-Gil was 21, just concluding her studies at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. In the city’s museums and galleries, depictions of ‘the nude’ (nameless, female, object-like) abounded to the degree that this subject, with its modernist associations with prostitution and wayward bohemianism, amounted to an obsession. In part, Sher-Gil’s self-portrait is a double tribute to Paul Gauguin and Vincent Van Gogh. She stands in three-quarter profile before a Japanese print or screen – a position and aesthetic reference familiar from Van Gogh’s self-portraits. As a ‘Tahitian’ she steps into the role of Gauguin’s dark-skinned young women, mute objects of the gaze. The shadowy figure of a man in dark clothing hovers behind her – perhaps Gauguin himself ?

As a young Hungarian-Indian woman, Sher-Gil felt an outsider: Indian in Europe, European in India, female in a forbiddingly male-dominated field. Her homage to Gauguin and Van Gogh is heartfelt but it is also subversive. She has inserted her naked body, rendered according to her own observation and skill, into the exotic fantasy realms that informed their work. She is the foreign ‘other’ and a sexual being, but she is also the author of her own portrait, a naked woman defying the idealised nude, her beauty human rather than divine

From the June 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Just the bare necessities of art

Nude Self-Portrait (c. 1509; detail), Albrecht Dürer. Klassik Stiftung Weimar. Photo: © Klassik Stiftung Weimar, Museen

Share

From the June 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

The cover of the first copy of this magazine carried the divine profile of the marble sculpture known as the Apollo Belvedere, a fitting motif for a mag that (at the time) covered both art and music. Question Apollo’s musical supremacy at your peril – Marsyas paid for such hubris with his skin. Considered the epitome of male beauty, the god inspired the earliest nudes in Greek art. Sculptures of Apollo from the early fifth century BC mark the emergence of a physical ideal that would endure for thousands of years: a carapace of muscle cladding the torso that transitions into the legs through deep iliac furrows.

The physical perfection of Apollo was mathematic in expression, marking him out as a divine being in human form. In the 18th century, the Apollo Belvedere was considered one of the greatest works in human history, caressed by the velvet prose of the art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann: ‘In gazing upon this masterpiece of art, I forget all else, and I myself adopt an elevated stance, in order to be worthy of gazing upon it. My chest seems to expand with veneration and to heave like those I have seen swollen as if by the spirit of prophecy…’ Thanks to this status, the Apollo Belvedere was looted from the Vatican Museum by Napoleon and installed in the Louvre, where it remained for 17 years. Until the early 20th century, it topped the list of plaster casts required for study of the figure at art schools and museums.

By the mid 20th century, the Apollo Belvedere had fallen from favour. In The Nude (1956), Kenneth Clark reminded readers that this supposed masterpiece was a Roman copy in marble after a lost Greek bronze, pointing out its ‘weak structure’ and ‘slack surface’. Not for Clark these Roman cover versions – in his view everything had gone downhill since Praxiteles carved his Aphrodite at Cnidos in the fourth century BC. ‘The drift of all popular art is towards the lowest common denominator,’ Clark lamented, ‘and there are more women whose bodies look like a potato than like the Cnidian Venus.’ As to whether there are more men whose bodies look like a potato than like a Praxiteles Apollo, the great art historian declines to comment.

Nude Self-Portrait (c. 1509), Albrecht Dürer. Klassik Stiftung Weimar. Photo: © Klassik Stiftung Weimar, Museen

The tuberous-bodied of this world are often naked in art, rather than nude, appearing as individuals, rather than ideals. We, the potato people, have bodies that are particular. Mortal, our conformation does not abide by the supposedly divine geometry of canonical proportions. For artists, scrutiny of the body in the mirror can reveal the fascinating vegetable truth. Albrecht Dürer first used a mirror (then a rare and precious device) to draw a self-portrait in 1484, when he was 13. Twenty-five years later he stared at his reflection with rather more intense scrutiny while drawing himself naked. Dürer thought deeply (and restlessly) about aesthetics, classical proportions and the idea that beauty might abide by fixed parameters.

While his Four Books on Human Proportion (1528) provided schemata for different body types, he rejected the idea that beauty could be achieved through a formula: it had to be drawn from life: ‘Without true knowledge, who will give us a reliable standard? I believe there is no one alive capable of perceiving the ultimate ideal of beauty embodied in the least of living creatures, let alone in a human being.’ Dürer does not look unpleased with the naked figure gazing back at him from the mirror. He’s a handsome, muscular man in his late 30s. He observes, intently, the impact of gravity on his genitals, and is unsparing of his lumpy love-handle and wayward knees.

This was a necessarily private work, but in drawing his potato self, Dürer was, in so many words, escaping the tyranny of Apollo. He portrayed his curious body as it was revealed to him through observation.

Self-Portrait as a Tahitian (1934), Amrita Sher-Gil. Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi. Courtesy the Estate of Amrita Sher-Gil

When Amrita Sher-Gil (1913–41) painted her mirror image more than four centuries later, she too was performing defiance, both social and aesthetic. In Self-Portrait as a Tahitian (1934) she stands stripped to the hips, her lower body wrapped in a length of cloth. Sher-Gil was 21, just concluding her studies at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. In the city’s museums and galleries, depictions of ‘the nude’ (nameless, female, object-like) abounded to the degree that this subject, with its modernist associations with prostitution and wayward bohemianism, amounted to an obsession. In part, Sher-Gil’s self-portrait is a double tribute to Paul Gauguin and Vincent Van Gogh. She stands in three-quarter profile before a Japanese print or screen – a position and aesthetic reference familiar from Van Gogh’s self-portraits. As a ‘Tahitian’ she steps into the role of Gauguin’s dark-skinned young women, mute objects of the gaze. The shadowy figure of a man in dark clothing hovers behind her – perhaps Gauguin himself ?

As a young Hungarian-Indian woman, Sher-Gil felt an outsider: Indian in Europe, European in India, female in a forbiddingly male-dominated field. Her homage to Gauguin and Van Gogh is heartfelt but it is also subversive. She has inserted her naked body, rendered according to her own observation and skill, into the exotic fantasy realms that informed their work. She is the foreign ‘other’ and a sexual being, but she is also the author of her own portrait, a naked woman defying the idealised nude, her beauty human rather than divine

From the June 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Share

Recommended for you

Helen Gordon charts the fall and cultural rise of the Ensisheim meteorite of 1492

Francis Haskell and Nicholas Penny’s landmark history of the afterlife of classical sculpture has been refreshed to give it even more longevity

Why aren’t more women artists gazing at men?

There is no great tradition of male nudes by women artists, but this underlines an asymmetry of power rather than a lack of female desire