From the November 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

This exhibition, the first retrospective of Nicolas de Staël’s work to take place in Paris in two decades, can be understood as an attempt to correct much of the received wisdom surrounding the work of this so-called peintre maudit. While his name carries only moderate weight outside his adopted homeland, the facts of his life have ensured his survival as a household name in France, creating a myth that complicates all analysis of the art on which it rests.

Born to aristocratic parents in St Petersburg in 1914, de Staël died, by his own hand, in Antibes in 1955. In the interim, he experienced more than his fair share of tragedy: his post-Revolutionary exile, and subsequent upbringing by foster parents in Belgium; the death of his long-term lover in childbirth; and an obsessive, unrequited infatuation that may have been a factor in his eventual suicide. He was intense of character and smoulderingly handsome: imagine James Dean, cast as a brooding, bohemian charismatic.

The curators here are at pains to place their subject at a distance from his posthumous cult. Instead, this is a scholarly, chronologically organised examination of the artist’s working methods, giving as much weight to oil sketches as to bona fide masterpieces. It is also a visually ravishing blockbuster, full of unexpected twists, turns and colourful punches to the gut. A good two-thirds of the 200 works here have been sourced from private collections, many of which are on public display for the first time since the artist’s death, allowing for what might be the most comprehensive show of his work to date.

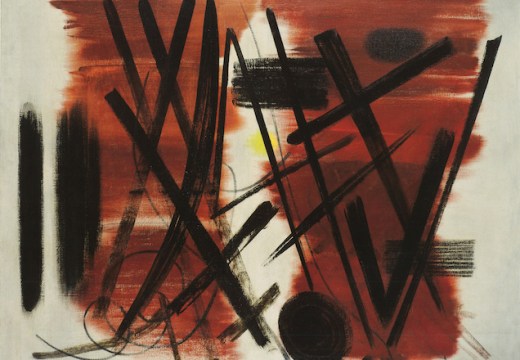

The brevity of de Staël’s career – it lasted little more than a decade – proves no obstacle: he was extraordinarily prolific, which allows for a hang that devotes at least a gallery to every year of consistent activity, plus a full room of ultra-rare juvenilia. What’s immediately apparent is the extraordinary breadth of de Staël’s practice. One moment we find him attacking sculpturally dense black impasto with a palette knife, the next creating geometric homages to Piranesi’s prison drawings; then, suddenly, he is drawing on Robert Delaunay to realise a blocky oil sketch of a floodlit football match, a study for his most famous (and, in its finished form, radically different) painting, Parc des Princes (1952, also on show).

Parc des Princes (1952), Nicolas de Staël. Private collection. Photo Christie’s; © ADAGP, Paris, 2023

It’s possible to swoon over these paintings for many different reasons: you can tell yourself that, in essence, this is the pinnacle of the ‘second School of Paris’, a dubious umbrella term used to cover any France-based artist with even the slightest stylistic similarity to the American Abstract Expressionists. This theory is refuted wholesale here: de Staël was never an instinctive painter and believed that the distinction between representation and abstraction was an absurd one.

Nor did de Staël compose entirely according to mood: even at his most bleak, he can’t resist the occasional ruby-red flourish. Indeed, such is the variety that it at times verges on parody. Frequently, you imagine him thinking: I can do commercial illustration; I can do creepy, Ensor-ish still life; I can do twee Dufy nautical scenes; I can do better than Cézanne (an artist he mysteriously described as ‘a pawn’.) Yet de Staël nearly always comes out on top, creating paintings that couldn’t possibly have come from another hand.

Consider Composition en noir (1946), his self-professed ‘first masterpiece’ – he destroyed most of his early paintings, though one view of the Pont de Bercy from 1939 is on show here – a web of night-black impasto from which sub-surface colours shine like gems. Or his many more explicitly representational works, where land meets water – by means of the landscapes he saw in the south of France towards the end of his life, or more of those Parisian bridges – into which one might read references to his status as a liminal painter, mixing representation with abstraction. Look at his sketches of Agrigento, or his paintings of other Mediterranean French ports: all bursting with colour, paint laid on mud-thick at shore level, feather-light for the sky.

Marseille (1954), Nicolas de Staël. Courtesy Catherine and Nicolas Kairis/Applicat-Prazan, Paris; © ADAGP, Paris, 2023

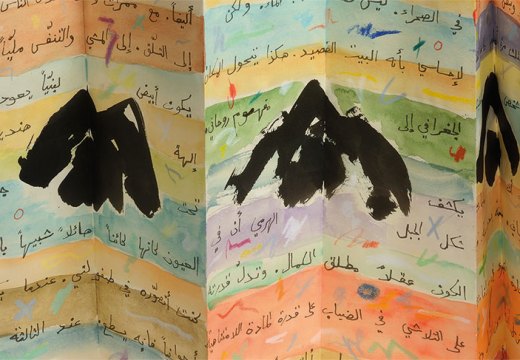

Nowhere is his virtuosity more evident than in the sublime middle section, dating from 1953–54. It’s no coincidence that this was the period in which de Staël moved from Paris to the south: his palette changes, he starts to favour orange, yellow and green over the blues he daubed over cardboard while painting en plein air by the North Sea. Seascapes evoke the hazy horizons of, say, Marseille, or the coastal resorts to its south. Landscapes, meanwhile, presage the visions of Etel Adnan.

The single best section is saved until last. Here, the work becomes inseparable from the biography. In 1953 or 1954, de Staël became fixated on Jeanne Polge, a married woman of means. Two life-sized nude sketches give some sense of his intensity of feeling. The painter begged Polge to leave her husband; she refused. According to a friend, in a diary entry for the winter of 1954, ‘de Staël [wanted] to kill himself. For a woman.’

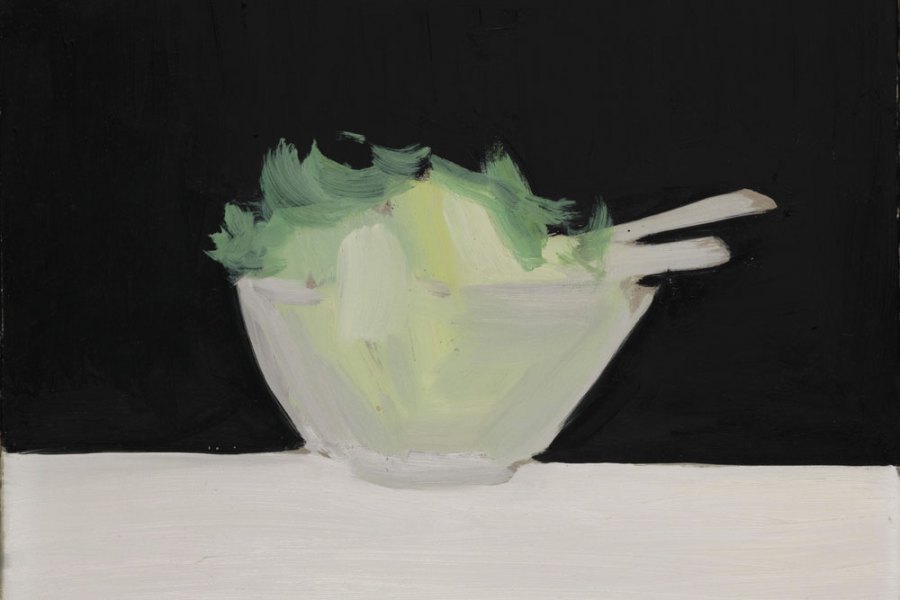

De Staël had drifted further and further from representation since the end of the Second World War, but in his last year pulled a volte-face: the oranges, reds and yellows of his high period gave way to bleak, North Sea grey. Abstraction, in turn, took a back seat. The de Staël of 1955 was a painter of grim maritime accidents and forlorn still life. We can’t be sure he was familiar with Morandi, but the two painters shared much in common. Time, it must be said, has served the Italian artist rather better.

Yet some of de Staël’s last paintings are among his best. Pitting a near-conical salad bowl against a black background, Le Saladier (1954) is a gem. The same is true of a vast and categorically weird vision of seagulls in flight, realised just days before his death. It seems ghoulish to speculate as to what this least predictable of artists might have done, had he lived. Although the show encourages us not to embrace the myth, it’s hard not to leave it feeling like a hero-worshipping adolescent, wondering what might have been.

‘Nicolas de Staël’ is at Musée d’Art Moderne, Paris until 21 January 2024.

From the November 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Has arts punditry become a perk for politicos?