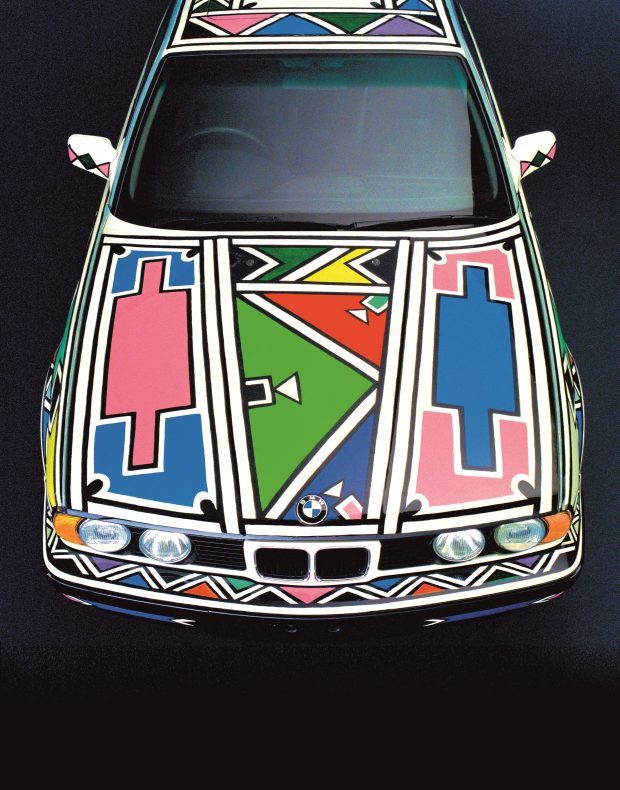

The essential story of South African art is currently parked in the Great Court of the British Museum. It is Esther Mahlangu’s BMW Art Car 12 (1991), an automobile painted with the exuberant patterns for which South Africa’s Ndebele population have become famous, and which the manufacturer commissioned to mark the end of apartheid. Certainly, Mahlangu’s car could be taken as an early example of the way tribal motifs have been commodified to market South Africa as a tourist destination. But it also embodies the tenacity of African artistic traditions, which were kept alive under the shadow of oppression by the incorporation of new materials and new ideas.

This search for continuity amid turmoil and plight is, I would argue, the key ingredient for any exhibition that steps into the domain of South African art and its modern history. And yet, as ‘South Africa: The Art of a Nation’ shows, this is a difficult thing to represent. While the exhibition includes wonderful artworks such as Mahlangu’s BMW, its wide scope means that we rarely glimpse the deep traditions from which they flow.

BMW Art Car 12 (detail), (1991), Esther Mahlangu. Photo: © BMW Group Archives

The show has a dual premise, presenting artefacts from the region’s history – a million-plus years of it – alongside artistic responses from the modern and contemporary eras. On some levels, this opposition works rather well. The habits and beliefs of Africans across millennia are hinted at by sculpted animals, elongated human figures, glowering busts, and objects weathered by time, which somehow still exude social and ceremonial importance. Meanwhile, the oblique manner in which the artworks try to interpret this glass-encased past seems to emphasise the profound changes that have distorted South Africa’s history over the last few centuries.

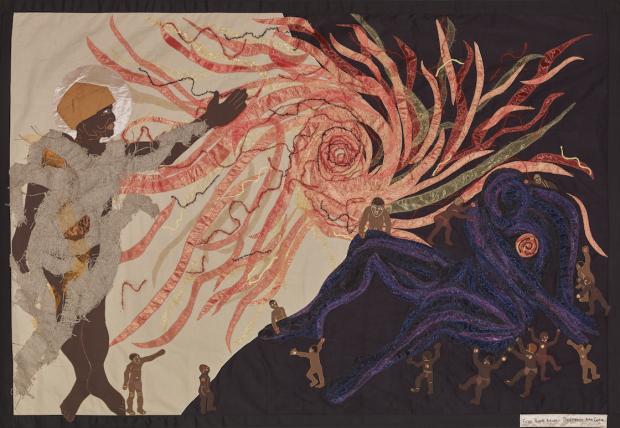

This reaching towards the past can be seen in the work of artists from the Bethesda Art Centre, whose vivid tapestry The Creation of the Sun (2015) explores the myths of their San and Khoekhoen ancestors; we can also see white artists trying to understand their place in the South African story. Bad Faith Chronicles (1997), a strangely moving piece involving plastic dolls pinned to a panel alongside biblical excerpts, is the artist Willem Boshoff’s take on the colonial exploitation of land.

The artefacts themselves tell fascinating stories. We see the gradual encroachment of Europeans into the African record: one rock painting, from around 1650, shows a Dutch galley sighted in the distance; another, two centuries later, shows settlers with their livestock and wagons. In the intervening period, ceremonial objects have assumed the shapes of snuff boxes and rifles. And a moment of special pathos comes in the form of a pair of leather sandals, handmade by Mahatma Gandhi, who gave them to Jan Smuts.

Ultimately ‘the art of a nation’ (unlike, perhaps, ‘the artefacts of a nation’) is simply too rich and emotive a subject to be shoehorned into a survey exhibition. There is, surprisingly, only one example of the extraordinary woodcuts and lithographs that came from the Rorke’s Drift Art and Craft Centre between the 1960s and ’80s. This body of artwork, facilitated by Swedish missionaries at a time when black artists were denied formal education, is a perfect example of an African heritage, in this case Zulu, moving into new media.

The Creation of the Sun , (2015), Bethesda Arts Centre. Photo: © The Trustees of the British Museum

There is also little sign of the unparalleled traditions of African ceramics and textiles, and very little of the folk art, such as wire sculpture and woven bowls, which has long been the artistic lifeblood of many African communities. These, perhaps, have been forgotten in the space between art and artefact.

The cursory treatment of some of these art forms points to a misapprehension of the fundamentally communal role of art during the centuries South Africa was being forged as a nation; this painful unification of more than a dozen different peoples led each of them to cleave to their own artistic identities. This misplaced emphasis stems largely, it seems, from a bias towards individual artists and artworks of heroic standing, rather than the endurance of traditions. Indeed, the only African craft that is properly substantiated here is wood sculpture, and this perhaps only because the examples depict inspirational individuals – Owen Ndou’s Oxford Man and Jackson Hlungwani’s Christ Playing Football (both 1992). If it seems patronising to associate Africans with anonymous craft, this says more about our attitudes to craft.

Yet the problem here is not so much a Western outlook as an anachronistic one. In the final and most contemporary two rooms of the exhibition, the curatorial approach is at its most successful. Here we encounter the fine art of David Goldblatt and William Kentridge; Mary Sibande’s fantastical maid’s garments and Candice Breitz’s ‘hijacking’ of an African TV drama; and, as background, a host of anti-apartheid memorabilia. The context is clear: this is South Africa communing with its history under the schema of contemporary art. It is important to realise what a radical difference this makes.

‘South Africa: The Art of a Nation’ is at the British Museum from 27 October 2016–26 February.

From the January issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home