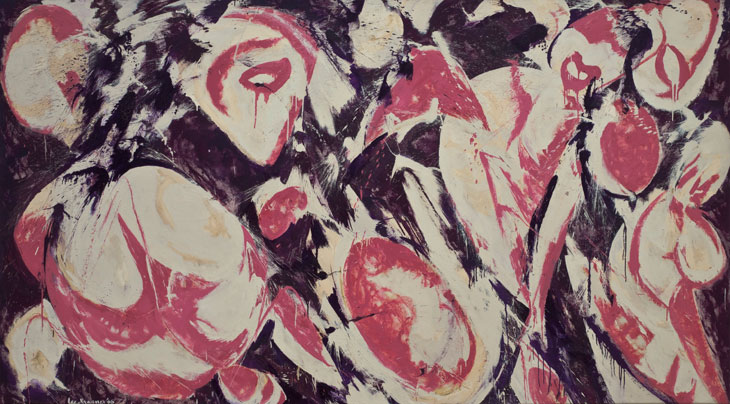

In Lee Krasner’s oil on canvas, Gaea (1966), different forms resembling body parts (an ear in the top left corner, an eyebrow above an eye, breasts, lips, an arm, buttocks) and ovoid shapes appear against swaths of purple, coded female by their creamy white and pink hues. Their relation to each other is difficult to pin down, and a fully articulated woman never quite appears: despite the size of the canvas, there doesn’t seem to be enough room for one complete body. There’s a story to be told, but it’s not yet in focus. This might serve as a decent metaphor for the Museum of Modern Art’s exhibition, ‘Making Space: Women Artists and Postwar Abstraction’, where the painting is now on view.

This is a flawed exhibition. On the one hand it tries to cover too much: the 100 or so featured works hail from an international roster of artists, and date from the end of the Second World War to the start of the feminist movement in 1968. Moving through painting, photography, sculpture, furniture, and tableware, you might feel you’re on a whirlwind trip with a tour guide who moves too fast, never letting you linger or adequately absorb your surroundings.

Untitled (1966), Eva Hesse. © 2017 Estate of Eva Hesse. Galerie Hauser & Wirth, Zurich

On the other hand, it’s been criticised for not doing enough. The exhibited artworks belong to MoMA’s permanent collection, but will only be visible to the public through 13 August, when they will be dispersed back into the museum’s stores and other rooms. Like the woman in Gaea, the artists are only partially represented; often, a single work is used to signify a woman’s entire oeuvre. Sometimes, those works are misleading. Several critics have written about these issues. In the Wall Street Journal, for example, Peter Plagens argues that the exhibition ‘seriously misrepresents the “achievements” of several artists in the show,’ mentioning works by Eva Hesse and Anne Truitt that don’t convey the extent of their mastery and innovation in sculpture. Ariella Budick is even harsher over at the Financial Times. ‘Making Space is a wishful title for a display so small, remote and ghettoised that it defeats the case it tries to make… A more accurate title would be Nowhere Near Enough Space,’ she writes.

All true. As MoMA undergoes its own expansion, the museum may want to look to other institutions, such as the Tate Modern, which have allocated more space to women as their capacity has grown. They should also offer more solo shows to women: a glance at the curators’ biographies reveals an emphasis on male artists’ accomplishments to date.

Collage, 353 (1949), Anne Ryan

But for all its flaws, the display does reveal some surprising affinities between artists’ works. Anne Ryan’s collages and Mira Schendel’s oil transfer drawings are some of the exhibition’s loveliest, most delicate pieces. Both women were poets, and both bring a poetic sense of distillation and precision to their visual art. On the other side of the spectrum, two Polish sculptors are responsible for some of the exhibition’s weightiest and most startling works. Alina Szapocznikow’s Belly-Cushions (1968) comprises five coloured, polyurethane casts of a woman’s stomach, their eerie forms implying violence and a disturbing objectification. Magdalena Abakanowicz’s Yellow Abakan (1967–68), a large, circular sisal form that hangs from the wall like a massive cape, proves that fibrework need not be delicate. Folding in on itself and fraying at the edges, it has a sense of drama absent from most of the other textile works in the exhibition.

Several exhibits demonstrate how these individual artists admired and supported each other. The wall text next to Eleanore Mikus’s Tablet Number 84 reveals that Louise Nevelson (also included in the show) donated the work to the museum. Lee Bontecou’s large untitled sculpture in welded steel and canvas also comes from an artist-collector – it’s a gift from Kay Sage Tanguy, a prominent Surrealist.

Any and all of these artists and themes could do with greater examination. You won’t find that here. But let the show at least be a guide pointing to new ideas about – perhaps even new exhibitions of – postwar abstraction that place female artists in the centre, among male peers. That is, after all, right where they deserve to be.

‘Making Space: Women Artists and Postwar Abstraction’ is at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, until 13 August.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home