An index is a list of names or subjects to be cross-referenced; it is a symptom, or an indicator which measures scale, value or success. Our index fingers are termed as such because they are our ‘pointing fingers’ – the fingers with which we single out, select, warn, admonish, unify and praise. In photography, the index is the basis of the medium’s ‘truth claim’: the assumption that traditional photographs accurately, and infallibly, depict reality. It is this relationship between object and subsequent image that allows us to persistently accept the photograph as evidence. The index of the photograph is the specificity of pointing a finger, what Roland Barthes termed the ‘that-has-been’.

Featuring 200 photographic images, ‘Collected Shadows’ at Stills Gallery is dependent on the continual, accumulative shock of the ‘that-has-been’. Selected from the Archive of Modern Conflict (AMC) and curated by its director Timothy Prus, the exhibited images span 165 years, numerous continents, personal histories and world-breaking events. The AMC was first established in 1991 as a repository for materials relating to the First and Second World Wars but has since expanded into a bank of over eight million images encompassing a ‘plethora of subject matter’. The democratic nature of the photograph is extended by its assimilation into the archive; images are attributed, in turn, to unnamed, named, professional, scientific, celebrated and amateur photographers. A signed Robert Frank silver gelatin print sits beside an image taken in 1920 by an unknown photographer. A Eugène Atget photograph is displayed alongside a plant study by Charles Nègre and an unnamed photograph of a solitary hat in a field.

Solar eclipse, Astronomer Royal’s expedition, Giggleswick, North Yorkshire (1927), unknown British photographer. Courtesy Archive of Modern Conflict, London

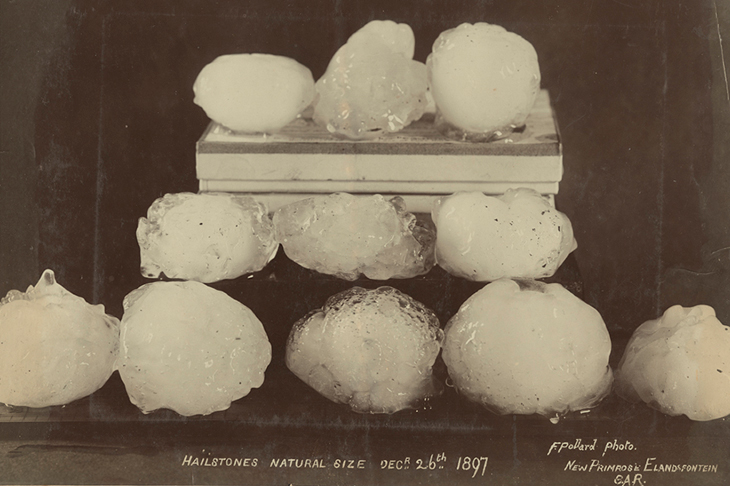

The works are hung in sporadic clusters on deep, aubergine-painted walls. The groupings loosely articulate elemental themes of fire, water, earth and air: burning vehicles and buildings, vast expanses of water and sky. A large Soviet Space Agency panorama of the moon’s surface taken in 1966 is displayed almost at ground level, beneath Antony Cairns’ monochrome stitched panorama of Dalston, from 2011. The repetitive rectangles of a paved east London street are juxtaposed with the elongated crop marks in an expansive Italian field. A photograph capturing the solar eclipse of 1927 mirrors the circular forms in one taken 40 years later by Czech photographer Vilém Reichmann, which shows two car tyres, floating in the watery reflection of a city. In one image, the black circle is a monumental void; in the other it’s an aberration. One is a document of historical significance, one a record of a personal discovery.

Plant Study (c. 1910), Bertha Jaques. Courtesy Archive of Modern Conflict, London

Threaded throughout the exhibition groupings, the alchemical blue of cyanotypes resurfaces. Cyanotypes are both volatile and resilient. Their detail fades when exposed to light but can be restored through hibernation, by re-placing the print in a dark environment. Bertha Jaques’ early 20th-century photogram cyanotypes are a direct physical imprint of her photographic subjects – the ghosts of rye and willow catkins made visible without a camera. Meanwhile, Frank Coster’s camera-manipulated Spirit Photograph from 1890 depicts three, impossible ghostly faces hovering above a woman seated for a portrait. Despite their different processes, both are an immediate rupture of the indexical image. While we understand that the world is not monochrome, it has largely been accepted since the 19th century that neutral and black-and-white tones are indicative of (past) reality. The monochrome reality of blue has not been afforded such a status. Blue is the colour of ruin, melancholy, illness; it has been the subject of philosophy enquiry and catalogued and analysed by numerous artists, filmmakers and writers.

The remit of the Archive of Modern Conflict is vast to the point of incomprehension. As Brian Dillon suggests in his catalogue essay, the archive might be viewed ‘as an incomplete, maybe interminable species of research in itself’. Across histories and geographies, ‘Collected Shadows’ scrutinises the photographic record’s apparent accuracy and stability. Images of scientific experiments abstract and enlarge their subjects so they appear cosmographic, or are blurred into opacity; chairs, jackets and hats levitate; and atomic mushroom clouds are hand-tinted to mirror the nostalgia of sunny holiday postcards. Planets, ghosts and traces of electricity are imprinted on film. And the inky blue of the cyanotype recurs, an indelible reminder of the precariousness of history.

‘Collected Shadows: The Archive of Modern Conflict’ is a Hayward Gallery Touring exhibition organised in collaboration with The Archive of Modern Conflict, London. The exhibition is at at Stills: Centre for Photography, Edinburgh, until 8 April.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home