Walter Benjamin observed that copies do not have ‘the here and now of the work of art’, but in this innovative study of the ‘cast culture’ of 19th-century Europe and North America, Mari Lending argues that casts create their own here and now, thereby reframing our understanding of originality, geography and history.

Plaster copies of sculpture were made from the 4th century BC onwards, but Lending’s subject is 19th-century, large-scale architectural reproduction – whether a doorway, a column, a frieze, or a façade. The canon included Egyptian, Assyrian, Persian, Indian, Greek, Roman, and gothic buildings, for, as Lending rightly points out, the casting of architecture is a historicising rather than a classicising phenomenon. In the early 20th century casts were dismissed as derivative and inferior, but in their heyday they were highly desirable objects produced with skill. Intended not to supercede the original building, but to record it or render it portable, architectural casts affected the perception of their referents, increasing their fame and elevating their status as ‘monuments’.

Plaster copies of sculpture were made from the 4th century BC onwards, but Lending’s subject is 19th-century, large-scale architectural reproduction – whether a doorway, a column, a frieze, or a façade. The canon included Egyptian, Assyrian, Persian, Indian, Greek, Roman, and gothic buildings, for, as Lending rightly points out, the casting of architecture is a historicising rather than a classicising phenomenon. In the early 20th century casts were dismissed as derivative and inferior, but in their heyday they were highly desirable objects produced with skill. Intended not to supercede the original building, but to record it or render it portable, architectural casts affected the perception of their referents, increasing their fame and elevating their status as ‘monuments’.

At the same time, however, casts were undeniably different from their progenitors. Stripped of the original’s incidental features, such as colour and material, a cast had greater clarity and legibility, capturing the essence of the original in an abstracted form. Plucked from their context, they brought new audiences into contact with buildings from far-flung places and allowed curators to construct new national and international historical narratives.

By charting the institutional fortunes of architectural plaster casts, from the genesis of architectural museums in the early 19th century to the destruction of cast collections a century later, as well as their renewed resonance in the digital era, Lending demonstrates that ‘both monuments and their representations are in constant flux’ and that tradition is ‘a process of continual reinvention’.

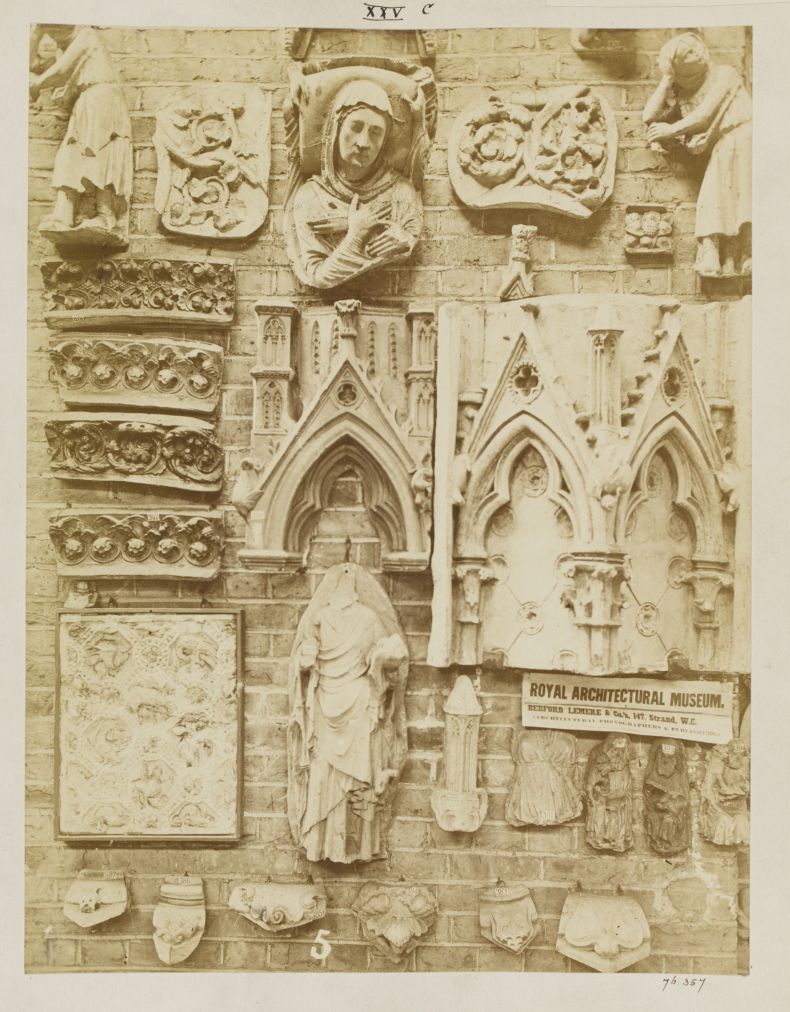

Photograph from c. 1872 of casts in the Royal Architectural Museum, London, including figures and canopies from Notre Dame, Paris, taken by Bedford Lemere & Co. Victoria and Albert Museum, London

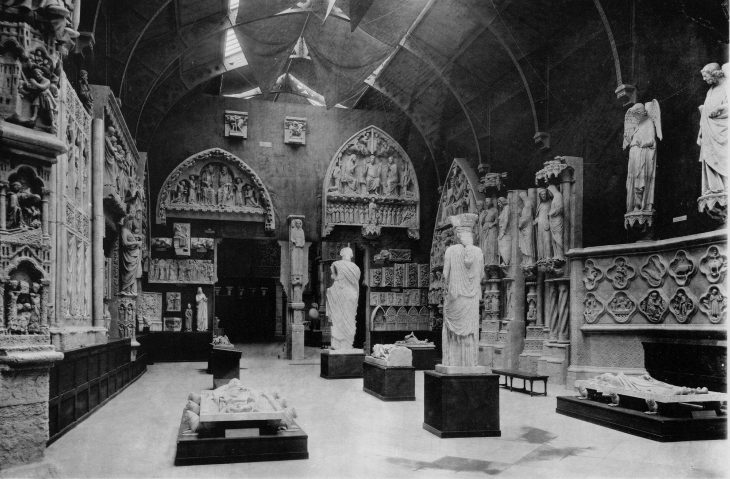

The 19th-century status of architectural casts was as didactic objects of the highest quality and the methodological priorities that underpinned institutional displays were chronology and comparison. From Sir John Soane’s idiosyncratic collection (left to the nation in 1837) to the Hall of Architecture at the Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh (which opened in 1907), cast collections in Europe and America aimed to be comprehensive and authoritative.

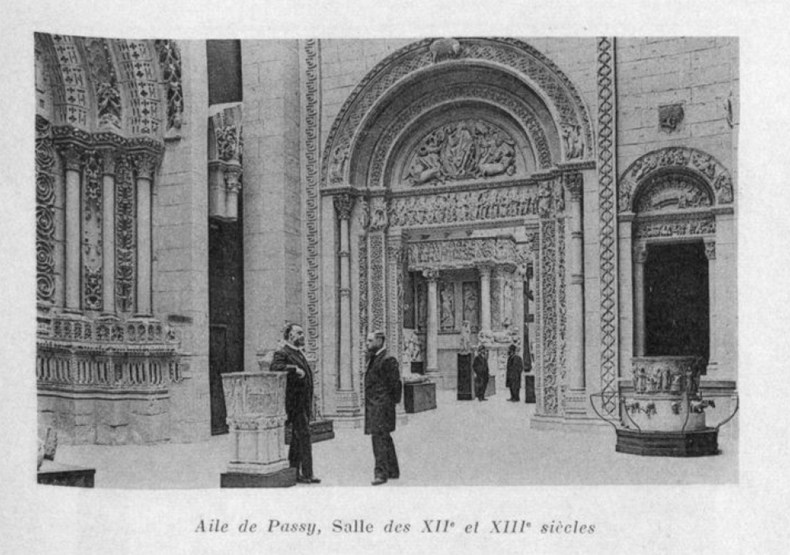

In London, the British Museum, the Royal Architectural Museum and the Crystal Palace all took a picturesque approach to the arrangement of their casts. The Trocadéro in Paris, by contrast, adopted a critical approach, emphasising great monuments of Gothic architecture to underline the importance of France’s medieval past. The staging of casts was not only a retrospective exercise, however. Lending argues that since ‘circulation is a condition of modernity’, the casts’ very mobility made them contemporary objects, even as they documented the past.

Twelfth- and 13th century galleries at the Trocadéro, Paris, from ‘Catalogue général du Musée de sculpture comparée au Palais du Trocadéro (moulages)’ (1910) by Camille Enlart and Jules Roussel. Courtesy Princeton University Press

Institutional cast collections were also defined by the desire to promote universal access to the highest quality art. The 19th-century culture of reproduction operated on the assumption that copies were both public and democratic and would facilitate mass education. Reproductions were not imitations but, in the words of an 1866 publication on photography, ‘true copies’ that would bring masterworks ‘fully within the reach of all as printing does good books’. Understood alongside photography and electrotyping – the other reproductive technologies developed and embraced in the mid 19th century – plaster casts lose their dusty pallor and become once more the arresting, modern representations that they were when new.

Although the purpose of the architectural fragment was that it functioned as a pars pro toto, in practice plaster casts had to be supported by photographs, models, and guidebooks – illustrated in this volume by quotations and photographs of long-lost displays.

Lending also exposes the practicalities and challenges of cast collecting. Casts were a booming trade in the late 19th century and museums competed for the most sought after examples. The availability of casts, even though they were multiples, was limited, especially towards the end of the century when the damage caused by taking moulds was finally acknowledged. Mould-making itself was often hampered by poor weather conditions, and transporting and reassembling the casts could be a gargantuan task: 195 crates were required to convey the cast of the Porch of Saint-Gilles from Marseille to Pittsburgh in 1906.

One of the strengths of Lending’s study is its generous definition of ‘cast culture’ to include representations of casts in literature. Her analysis of original and copy is focused through the lens of Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, in particular the account of the young narrator’s obsession with a plaster cast of a portal in a museum, and his pilgrimage to see the ‘real’ building. It results for him in bitter disillusionment as, unlike the perfect cast, the original is caught in ‘the tyranny of the Particular’. This allows Lending to argue in favour of the alternative reality of the reproduction, and to explore the affective qualities of architecture, an interest that doubtless owes much to this study’s origin within the emerging scholarly area of architectural exhibitions.

Lending is concerned with both the casts’ 19th-century context and their powerful legacy. This is manifest in a case study of Yale University’s architecture department, where in 1950 Josef Albers exiled the casts from the teaching regime and the building. Paul Rudolph reclaimed the same casts in 1963 when he reincorporated them into the Art and Architecture Building with an allusive rather than a didactic agenda.

Penthouse at the Art and Architecture Building at Yale, decorated with casts of bas-reliefs from Queen Hatshepsut’s funerary temple at Deir el-Bahari in the Theban necropolis. Courtesy Princeton University Press

The drive to preserve via casts reached a high point in 1867 when Henry Cole, first director of the South Kensington Museum (as the V&A was then known), secured the signatures of 15 European princes in support of the ‘Convention for promoting universally Reproductions of Works of Art for the Benefit of Museums of all Countries’. One hundred and fifty years later, in May 2017, the V&A launched an initiative to produce new guidelines on the Reproduction of Art and Cultural Heritage (ReACH). It is timely amid new contexts for preservation and when reproduction technologies are advancing, that Lending’s analysis reveals the significance of their plaster precursors.

Plaster Monuments: Architecture and the Power of Reproduction by Mari Lending is published by Princeton University Press (£41.95).

From the January issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home