The Italian Renaissance is flavour of the month again, with major exhibitions on Giorgione and Botticelli running simultaneously in London at the Royal Academy and Victoria and Albert Museum. The conjunction of these shows confirms the enduring appeal and bankability of Italian Old Masters, but neither is a straightforward monographic exercise. The same may be said for the season’s principal Renaissance exhibition in Italy, that on Piero della Francesca at the Musei San Domenico, Forlì. The manner in which each departs from convention tells us something about our current relationship with the artistic legacy of the Italian Renaissance, and where that relationship may be heading in the future.

While the public appetite for Renaissance painting remains thoroughly Vasarian in its demand for headline artists, these exhibitions play with those expectations in different ways. The curatorial adventure that drives them coincides with a spike in research on contemporary receptions of the Italian Renaissance – on present-day encounters with Renaissance art and architecture, in contexts as diverse as The Sopranos and Assassin’s Creed. One recent anthology on the topic argues that the continued ‘5-star’ prestige enjoyed by Renaissance art masks deeper transformations related to consumption and commodification, as cultural tourism, air travel, and digitisation change our relationship with the Renaissance past to a degree not seen since the advent of photography and rail travel in the second half of the 19th century. The failure or unwillingness of scholars to engage with such trends, so the argument goes, explains why the increased popular enthusiasm for Renaissance Italy coincides with an apparent decline in numbers choosing to study the period and its art at university.

Venus, 1490s, Sandro Botticelli. Photo: © Volker-H. Schneider

These tensions are openly aired in ‘Botticelli Reimagined’ at the V&A (until 3 July), a daring and knowingly controversial affair that arrived in March after its first leg in Berlin. The three sections of the exhibition turn chronology on its head, opening in the near-present with evocations of Botticelli in cinema, fashion and contemporary art before shifting focus to the artist’s rediscovery and reception in the 19th century. Botticelli himself is saved up as a grand finale. The initial encounters upend any expectation of a sedate Old Masters experience: the exhibition opens with a video loop of Ursula Andress (in Dr. No) and Uma Thurman (in The Adventures of Baron Munchausen) evoking the Birth of Venus in film. The first room is dedicated to the quotation, appropriation and exploitation of Botticelli in contemporary art and fashion or – in the language of the catalogue – to ‘Botticelli as Brand’. John Berger’s prescient words from 1972, originally spoken over the Ways of Seeing presenter cutting the face of a Botticelli Venus from its frame to make his own postcard, are stressed here in the catalogue foreword: ‘Today we see the art of the past as nobody saw it before…all paintings are contemporary.’ The sequence of the V&A show also implies that to access the historic, authentic Botticelli, we have to pierce the mist of contemporary myth.

First panel from Scenes from the Story of Nastagio degli Onesti, 1483, Sandro Botticelli. Museo del Prado, Madrid

And pretty acrid fog some of it is too, especially the coarse printings of the Birth of Venus on a Dolce & Gabbana suit and dress. The show could have made its postmodernist points more efficiently. The highly diverse opening section spans a full century with only Botticelli allusions (acknowledged, unconscious or alleged) as a tenuous, sometimes myopic unifying thread. The citations are not always readily apparent. The largest exhibit in the show is Bill Viola’s beautifully meditative video frieze The Path, which took some formal inspiration – by the artist’s own account – from Botticelli’s cassone panel narratives of Nastagio degli Onesti. The rhythmic trees establish similar compositional layers, but Viola’s peaceful troop of actors owes nothing to the sadistic hunting scenes that Botticelli drew from Boccaccio, those ‘somewhat unpleasant’ iconographies that ensured the National Gallery passed on the Nastagio cassoni when the opportunity to acquire them arose in 1863. The Prado eventually accepted them in 1941 as part of a larger bequest and they have not made the journey from Madrid to South Kensington, leaving Viola’s elegiac film to make the point by itself. The example confirms that where juxtapositions are less than tightly presented, our understanding of the historic artist – whose name still carries the show – can be dissipated rather than enriched by the contemporary.

Such quibbles are on the whole trumped by the refreshing candour shown by the curators of ‘Botticelli Reimagined’, by their willingness to acknowledge and comprehend the late 20th-century appropriation and commodification of Renaissance art – trends that may frustrate purists and scholars but which are now unarguably part of any contemporary engagement with the period. What we cannot fail to notice in the V&A display is that Brand Botticelli is essentially the Uffizi’s Birth of Venus, which inspires seemingly endless opportunities for the artistic exploration of gender and sexuality while also serving as a globalised shorthand for western painting tout court. Co-curator Stefan Weppelmann reflects that ‘the present has actually made this painting part of itself, thrusting the original body of work and its creator increasingly into the background’. In addition, the catalogue usefully clarifies how the Birth of Venus’s pre-eminent celebrity is a decisively 20th-century phenomenon, fired by its inclusion in the Mussolini-backed touring exhibitions organised between the wars. The picture is unlikely to ever leave Florence again, but it came to the Royal Academy in 1930 and at the start of 1940 was on display at MoMA in New York before returning to Italy across the wartime Atlantic.

Pallas and the Centaur (c. 1482), Sandro Botticelli. Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence

The second part of the V&A show travels back into the 19th century, with the slick black design of the opening rooms giving way to a powder-blue carpeted domesticity. We follow the story of Botticelli’s rediscovery in the period as the painter of pious Madonnas and the illustrator of Dante, while the Uffizi and the Accademia dithered over how to display the Primavera and the Birth of Venus. In the final section the visitor finally comes face to face with Botticelli himself. The period aesthetic of the previous rooms is superseded by the modernist white cube, as if the exhibition is turning full circle back to the present. Anxious to deliver on the conventional monographic promise as well as subverting it, the V&A publicity reminds us more than once that this is the largest assembly of paintings by Botticelli ever gathered together in the UK. No less than nine tondi roll along the far wall (11 if one includes the adjacent fragments) – a massed display that could easily have been an exhibition by itself, or else streamlined by excluding some of the weaker workshop pieces. Mediocre bottega products like the Berlin Christ Redeemer may communicate the complex output of Botticelli’s shop but, having travelled so far, the visitor now needs to know what the fuss is about. Thankfully, the curators have secured a core of knock-out loans to anchor this section: the Mystic Crucifixion from Harvard, the Chigi Madonna from Boston and, most extraordinarily, the Pallas (or Camilla?) and Centaur from the Uffizi. Of course the Birth of Venus cannot be here, but the V&A has the next best thing in the two standing nudes from Berlin and Turin that reprise the original’s central goddess. Seen side by side their proportions are identical, reminding visitors before they exit that the long story of copying and iconising the Birth of Venus began in Botticelli’s own workshop. With its emphasis on the complexities of collaboration, this closing section – ostensibly the truly monographic element of the exhibition – undercuts the idea of a single author.

Madonna della misericordia (1445–55), Piero della Francesca. Museo Civico di Sansepolcro

The V&A’s approach to Botticelli finds a remarkable parallel in ‘Piero della Francesca: Exploring a Legend’ at the Musei San Domenico, Forlì (until 26 June), the latest in a series of ambitious shows staged by Gianfranco Brunelli, the museums’ energetic director. Piero himself is represented by four autograph paintings and a manuscript of his treatise on perspective, but the most original and important passages of the exhibition explore the painter’s rediscovery in the 19th century and his decisive significance for Italian painters between the two world wars. The English role in the early appreciation of Piero is given due prominence through Austen Henry Layard’s drawings of the Arezzo frescoes from 1855, followed by the watercolour copies now in the V&A commissioned by the Arundel Society. Not to be outdone, the French commissioned much larger copies by Charles Loyeux in the 1870s – loaned to Forlì as impressive alternatives to the frescoes themselves – which the young Georges Seurat would have seen hanging in Paris’s École des Beaux-Arts.

However, the dominant protagonist of the Forlì show is undoubtedly the Italian art historian Roberto Longhi, whose writings in the 1910s and ’20s crystalised Piero’s status as the key historical reference for Italian painters of the metaphysical school and Novecento movement. The dual focus is asserted in the opening room, where Francesco Laurana’s bust of Battista Sforza (c. 1474), standing for Piero’s impact on his Renaissance contemporaries, faces off against Carlo Carrà’s Engineer’s Lover (1921). The exhibition publicity powerfully juxtaposes Piero’s Madonna della Misericordia (1445–55) with Felice Casorati’s Silvana Cenni (1922). The closing room takes Piero to America through the work of Balthus (who knew and admired Piero’s work) and Edward Hopper (who may or may not have done). The 20th-century story of Piero – the modernist painter’s painter par excellence – could easily have been extended, and the curators are probably wise to call a halt when they do. There is no room for the Piero-obsessed Philip Guston. Nor for the peculiarly British infatuation with the ‘Piero trail’ (Aldous Huxley, Kenneth Clark, John Pope-Hennessy, John Mortimer et al), leaving plenty of scope should the National Gallery choose to build a show around its exceptional trio of Piero masterpieces. Original Pieros are harder to come by than Botticellis, and the four autograph works at Forlì were surely selected principally on the basis of their availability. Together they just about carry the exhibition, thanks above all to the freshly restored Madonna della Misericordia. But the inevitable absence of major works is, if anything, more keenly felt when telling the story of an artist’s later reception and reputation.

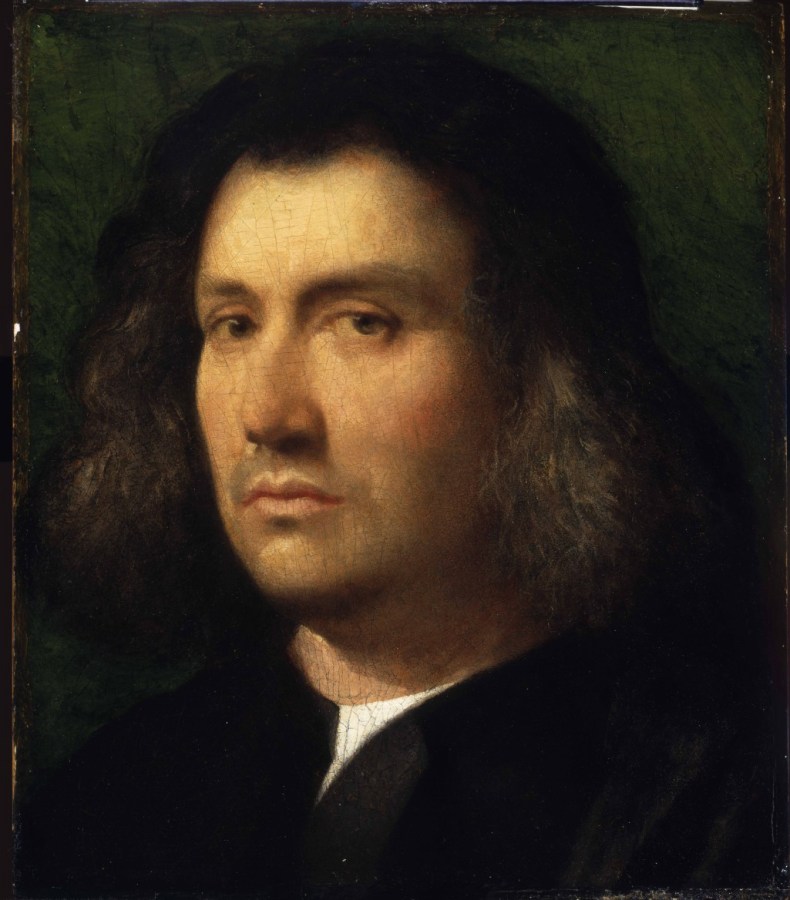

Back in London, different concerns exercise the curators of ‘In the Age of Giorgione’ in the Royal Academy’s Sackler Galleries (until 5 June). In their catalogue essay, Simone Facchinetti and Arturo Galansino carefully contrast the burgeoning myth of Giorgione with the handful of contemporary documents that have come down to us, principally concerning the painter’s death in 1510. ‘Each age invents its own Giorgione,’ they caution, paraphrasing Bernard Berenson’s admission: ‘Every critic has his own private Giorgione.’ Both Botticelli and Piero slipped into obscurity after their deaths to be revived in the 19th century. By contrast, works by Giorgione have been consistently prized down the centuries, with the result that hundreds of paintings have been attributed to him at one time or another. While the oeuvres of Botticelli and Piero are relatively stable, there is precious little agreement about what Giorgione painted. The fixed points in the RA show are the superlative Terris Portrait, which bears an early inscription confirming Giorgione’s authorship, La Vecchia, listed as by Giorgione in 16th-century Vendramin inventories and, so the curators assert, the Giustiniani Portrait, undocumented prior to 1884 but enjoying widespread support as an early work. Four further paintings on display are given to the master in straightforward terms, plus the Three Ages of Man, which at the time of writing had yet to arrive from the Palazzo Pitti, while five more are tentatively classed as ‘attributed to Giorgione’. The same caution pervades the rest of the catalogue, which juxtaposes Giorgione with contemporary works by Giovanni Bellini, Dürer, Sebastiano del Piombo, Titian, Lorenzo Lotto and lesser lights like the Bergamasque Giovanni Cariani. Even within these straitened confines, doubts will persist. Can the young man from Budapest really be by the same artist who painted the penetrating Terris Portrait? Facchinetti and Galansino offer an unusual but refreshingly open defence of their approach. They characterise their exhibition as ‘highly experimental’, presenting Giorgione’s art ‘in the jumbled state in which we see it, without our concealing any of its complexities’. The visitor is invited to participate in a process of reappraisal in the expectation that the exhibition will change how the artist is perceived.

Portrait of a Man (‘Terris Portrait’) , (1506), Giorgione San Diego Museum of Art

Organisers of Renaissance exhibitions have to grapple with a particularly difficult loan environment, as securing significant pictures, especially of panel paintings, requires ever more negotiation and leverage. Omissions as much as inclusions determine the shape of a show, and expansive exhibitions are sometimes pinned on very small kernels of undisputed autograph works. The pessimistic reading dwells on the growing difficulty of presenting Renaissance artists as coherent figures in themselves, or on the crutch of using contemporary art to reach the visitor numbers needed to make major shows economically viable. Increasingly specialised academic research and conservation analysis complicates as much as it clarifies, while the prevailing template for monographic shows is out of step with the social and theoretical preoccupations of much recent research in the field. Within academia, the centrality of Italian Renaissance art for an increasingly globalised art history is no longer a given.

But the optimist remembers that in the wider world the art of the Italian Renaissance has never been more popular or present. The task for academics and curators alike is to join up our ever richer understanding of a distant historical period with this broader awareness and appetite – much of which remains tenaciously neo-Vasarian. In their different ways, the three shows discussed here speak to this challenge. The willingness of their curators to foreground issues of reception, appropriation, decontextualisation, and authenticity so forcefully within the monographic envelope re-energises the format and offers fresh strategies for the future.

From the May issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home