From the February 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Even with rose-coloured glasses, it would be hard to look past the fact that global auction sales fell a cumulative 19 per cent at Christie’s, Phillips and Sotheby’s in 2023, racking up a rather sobering $11.6bn, some $2.1bn less than in 2022. These numbers, provided by the London-based art market analysis firm ArtTactic, signal a kind of art-market correction. Bidders have become more hesitant – happier to watch and wait.

‘I think the big story in 2023,’ says New York-based art advisor Mary Hoeveler, ‘was the disconnect between buyer and seller expectations in terms of pricing and that prices are still too high. There’s plenty of demand but buyers are expecting things at lower prices now than they were paying in 2021 and early 2022 and I still feel that hasn’t aligned itself.’

A good example of this disconnect was the single-owner evening sale, at Christie’s New York in May, of works from the estate of the late Boston mega-collector Gerald Fineberg. It hammered in $124.7m (before fees), well shy of the pre-sale expectation of $163m–$235m. Even with the tacked-on premiums, pushing the tally to $153m, it was a jaw-dropping miss.

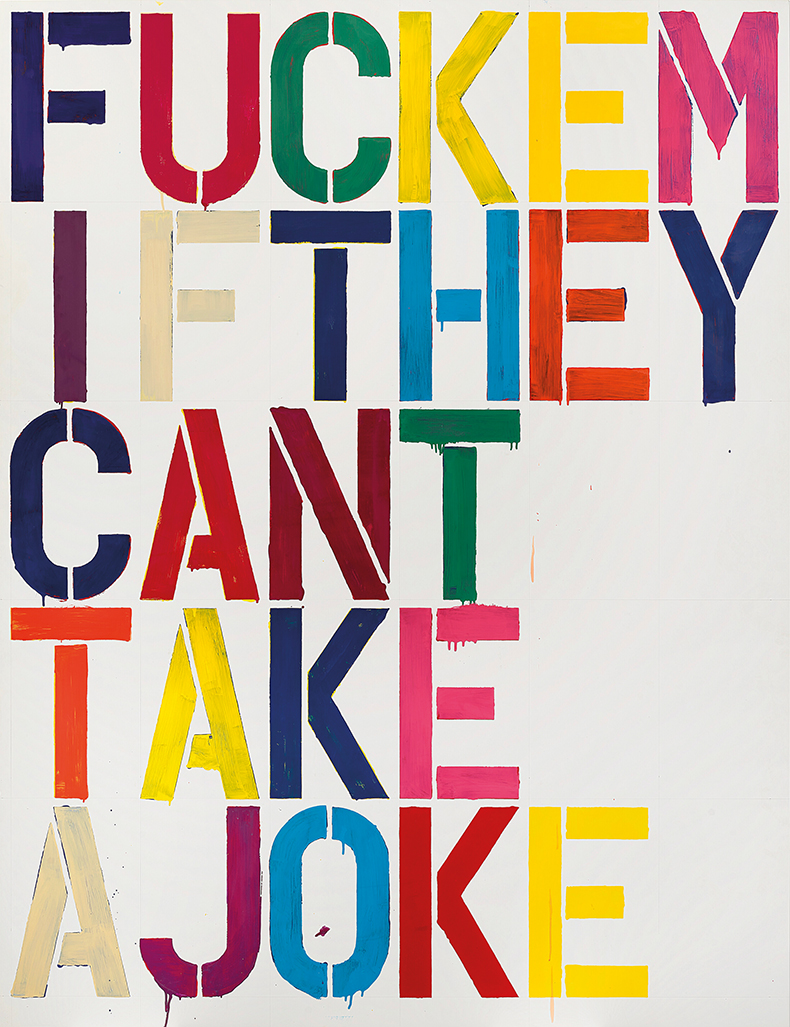

With all of the 65 lots coming to market ‘naked’ – that is, without any guarantees from Christie’s or third parties that usually insure such collections – and with reserves set low, prices were decidedly flat. Christopher Wool’s large-scale text painting in multi-coloured capital letters spelling out ‘FUCK EM IF THEY CAN’T TAKE A JOKE’ (Untitled, 1993) made $10.1m against an estimate of $15–$20m. Willem de Kooning’s juicy abstraction East Hampton III (1977) made $3.7m against expectations of $6m–$8m, while Gerhard Richter’s Badende (‘Bathers’; 1967) – a meticulous reproduction in paint of a blurred-out photograph, reminiscent of Delacroix for its heaping of bodies and virtuosic brushwork – realised $9.6m against an estimate of $15m–$20m. The affair set teeth on edge.

Untitled (1993), Christopher Wool. Courtesy Christie’s New York

After the sale, like a soldier stoically acknowledging defeat, Christie’s CEO Guillaume Cerutti told assembled journalists: ‘It’s a good reflection of the market.’ Josh Baer, a New York-based art advisor and CEO of the Baer Faxt newsletter, also suggests that the sale be understood as part of a bigger picture. ‘People look at the Fineberg sale as a flop,’ he says. ‘I’d say given what he spent on art, maybe it wasn’t a flop. I’d like to have that $153m as my flop […] If Paul Allen had died this year [2023], we’d be having a different discussion.’ The sale of Allen’s collection in 2022 at Christie’s delivered a record-setting $1.6bn.

Focusing on prestigious single-owner sales is an important way to gauge the state of the market. In November, the sale at Sotheby’s New York of the estate of the collector and philanthropist Emily Fisher Landau told a different story, garnering $406.4m.

Unlike the Fineberg sale, all of the 31 lots offered from Fisher Landau’s collection were fully guaranteed, either by Sotheby’s or anonymous third parties. Auctioneer Oliver Barker received the symbolic white gloves immediately after the last lot sold – but of course, that it would be a ‘white-glove’ sale (auction parlance denoting that all lots have sold) was a foregone conclusion.

Pablo Picasso was the star of the evening. Femme à la Montre (1932) – depicting his lover Marie-Thérèse Walter, prominently sporting a wristwatch – brought in $139.4m with fees against an unpublished estimate in the region of $120m, making it the most expensive work of art sold at auction in 2023.

Despite the big tally, many of the lots presumably sold to the third-party guarantors since bidding was mostly quiet, apart from a few notable exceptions – an exquisite Agnes Martin abstraction, Grey Stone II (1961), shot to a record $18.7m against an estimate of $6m–$8m. ‘Guarantees are very important,’ Hoeveler says, ‘not just in incentivising sellers but instilling confidence in the marketplace in general. I feel that 2023 can be characterised as a risk-averse market as an overall frame of mind.’

If art-market rumours are true that Sotheby’s guaranteed the Fisher Landau trove at $450m, beating their arch-rival Christie’s for the chance to win the market-share prize, one wonders if the house managed to break even on their bet.

‘The family did quite well,’ says Philip Hoffman, founder and chief executive of Fine Art Group, an art advisory and investment firm. ‘[They] got their $450m. What the economics were for Sotheby’s is another matter.’ As Hoffman sees it, ‘2023 was a pretty tough year and I think that the auction houses navigated very carefully and cleverly through the market. [They] clearly gave signals of a reasonably solid market because they advertised 90-per-cent-plus sold lots and some strong results.’

El Gran Espectaculo (The Nile) (1983), Jean-Michel Basquiat. Courtesy Christie’s New York

Other qualified success stories of the year include the 30-lot sale of the Netherlands- based Triton Collection Foundation at Phillips New York in November; with every lot guaranteed, the auction brought in $84.7m. It was led by Fernand Léger’s jubilant piece of cubism, Le 14 juillet (c. 1912–13), which made $17.6m against an estimate of $15–$20m, and by Pablo Picasso’s Femme en corset lisant un livre (c. 1914–18), which sold for $14.8m against an estimate of $15–$20m. (The art historian Pierre Daix characterised the painting as an example of ‘amorous Cubism’).

Beyond that trio of single-owner sales, there is still an evident hunger for standout works, defined by rarity and beauty. Gustav Klimt’s final painting, Dame mit Fächer (‘Lady with a Fan’; 1918) fetched £85.3m at Sotheby’s London last June against an unpublished estimate in excess of £65m, making it the most expensive work of art to sell at auction in Europe. It sold to an anonymous Chinese telephone bidder, raising hopes that the critically important Asian market was back in full swing after a temporary lull. In May – two days before the Fineberg sale became the canary in the coal mine – Christie’s New York sold Jean-Michel Basquiat’s mural-sized figurative canvas, El Gran Espectaculo (The Nile) (1983), for $67.1m against an unpublished estimate. It was one of 34 Basquiats sold at auction in 2023, bringing in a total of $202.2m – a figure second only to the $466.5m raised by the 214 Picassos that sold last year (figures courtesy of ArtTactic).

Work by the younger generation of contemporary artists has long been more likely to set off bidding fireworks, and last year was no different. The 31-year-old painter Jadé Fadojutimi’s large-scale, colour-charged abstraction Quirk my mannerism (2021) set a new record for the artist of $1.93m at Phillips New York in November, against an estimate of $600–$800,000. Among the Old Masters, the top result was for Rubens’ wonderfully gory Salome Presented with the Head of Saint John the Baptist (c. 1609), which sold for $26.9m against an estimate of $25–$35m at Sotheby’s New York last January. It previously sold at the same house in 1998 for $5.5m.

‘When an opportunity presents itself,’ Hoeveler notes, ‘even in a market where people are cautious and risk averse, they will step up to purchase these kinds of once-in-a-lifetime-opportunity works. That’s always been the case and I think that always will be the case.’

Salome Presented with the Head of Saint John the Baptist (c. 1609), Peter Paul Rubens. Courtesy Sotheby’s New York

From the February 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home