Christopher Bedford is hell-bent on putting Baltimore on the museum world stage. When he competed with 270 others for the job of Director of the Baltimore Museum of Art (BMA) in 2016, he asked the recruiting interviewer what the board was looking for: someone to make this the most dynamic and relevant civic museum for Baltimore and a role model for others, was the answer. ‘I knew I’d found my home,’ he recalls. He got the job.

The BMA, Bedford’s home, was founded in 1914 as an idea, with no collection. Since then, locals have been generous, and today the museum holds 95,000 works of art. The crown jewels are the 3,000 pieces left to the museum by the Baltimore sisters Claribel and Etta Cone, whose collection was rooted in visits to Matisse and Picasso’s Paris studios, where they shopped with the family’s textile fortune: it includes 500 works by Matisse (altogether, the BMA has 1,000 pieces by Matisse, the largest holding of his work in the world). The Cone collection arrived in 1949, on Etta’s death, Claribel having stipulated in her will 20 years earlier that the BMA should get it if ‘the spirit of appreciation for modern art in Baltimore became improved’. The Cones’ distant cousins, Blanche Adler and Saidie May, collected new Surrealist art expressly to give the museum (some pieces were in the recent show ‘Monsters & Myths: Surrealism and War in the 1930s and 1940s’), as did another Baltimore collector, Jacob Epstein, whose Old Master gifts included Titian’s Portrait of a Gentleman. About 18,000 French mid 19th-century works and some artists’ palettes gathered by the Baltimore dealer-collector George A. Lucas – who spent decades in Paris working for American collectors – arrived in 1933 to enrich the prints, drawings and photographs holdings, among the largest in any US museum.

Blue Nude (1907), Henri Matisse. Baltimore Museum of Art © Succession H. Matisse/DACS 2019

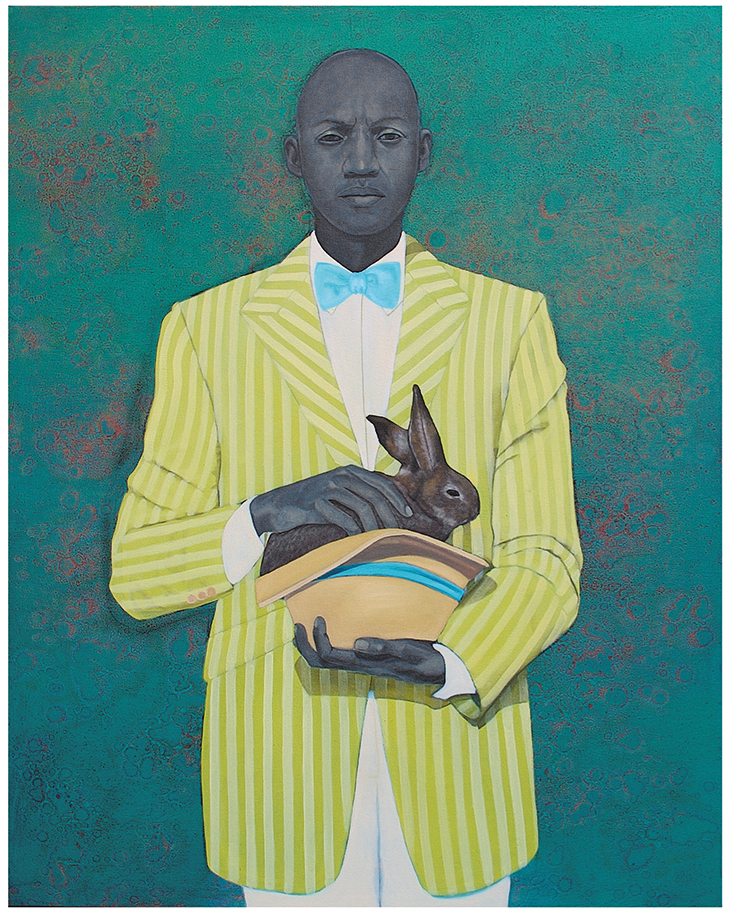

Bedford says he was ‘drawn to its vast collection and its extraordinary quality’, but he was also struck by the asymmetric relationship between the ethnicity of visitors to the museum and the city’s population: ‘Inverse,’ he says bluntly. His challenge, backed up by his deep belief in the social power of art history, is to change this. A Matisse Study Center is on the way. The American Wing is being rethought and reinstalled – last year, the BMA sold seven major works, including two of their 90 Warhols, to fund purchases of works by artists of colour and women, such as Amy Sherald.

The history of Baltimore, a port-city in Maryland, on the very edge of the southern states, is complex and contradictory. After the arrival of the first English ships in 1634, a wealthy city and a sophisticated elite were supported by tobacco, grain and sugar plantations, and the huge port. The city played an important role in the Revolution and the war of 1812 – the words of ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ refer to the Battle of Baltimore. The artist and museum entrepreneur Charles Willson Peale and his son Rembrandt opened possibly the first purpose-built museum building in the New World here in 1814. After the Great Baltimore Fire of 1904 destroyed more than 1,500 buildings, visionary planning made Charles Street – where the BMA and the city’s other world-class art collection, the Walters Art Museum, are sited – the city’s spinal boulevard, and Frederick Law Olmsted Jr’s grand plan for the city’s parks was second only to Boston’s.

Striding lion (5th century AD), Antioch (present-day Turkey). Baltimore Museum of Art

But there is an underside to this history: the plantations that sustained Baltimore’s prosperity were worked by slaves, and in the Civil War many Marylanders fought with the Confederacy. The Baltimore segregation ordinance, passed in 1910, forbidding black or white residents from moving into a block where they would be in a minority, was the first of its kind in the United States. Over the 20th century, migration from the deep South and ‘white flight’ meant that the city had an ever larger proportion of African-American citizens – today, they make up 64 per cent of a population of around 600,000. The riots that followed Martin Luther King’s assassination in 1968 were among the worst in the country.

These days, when Baltimore is mentioned, more people are likely to think of the HBO series The Wire (2002–08), about drug dealers and municipal corruption, created by the city’s superstar chronicler David Simon, than of the 298 Baltimore districts and buildings on the National Register of Historic Places. Among some 40 museums are fine historic mansions such as Evergreen, formerly owned by the railroad magnates the Garretts. Many already benefit from some innovative museum thinking, too – the lively Baltimore Museum of Industry, housed in an old cannery; the nearby American Visionary Art Museum, dedicated to outsider art, given a site on condition it cleaned up land polluted by a copper paint factory and a whiskey warehouse; and the Peale Center, which sent its collection off to the Maryland Historical Society in 1998, and has recently reopened as a community-oriented museum.

A 15-minute drive from the city centre, Baltimore businessman David Cordish and his wife Suzi installed their contemporary art collection at their Live! Casino & Hotel last July, a project Suzi Cordish calls ‘art in unexpected places, at unexpected hours, reflecting the energy of Baltimore’ – works by Jennifer Steinkamp, Chris Doyle, Sam Gilliam and others are on public display in the hotel and convention spaces 24/7. An hour’s drive takes you to Glenstone, where last autumn Maryland-raised Mitchell Rales and his wife Emily reopened their museum of classic modern art amid 230 acres of rolling hills. ‘Our goal was to collect seminal works of art made since World War Two and give a global perspective of what’s been going on,’ says Emily Rales. Purposely encouraging visitors to slow down and enjoy a contemplative and intimate experience with art and nature, it’s a ten-minute walk from the entrance, through fields and meadows dotted with sculptures, to reach Thomas Phifer and Partners’ refined galleries, lily-pool and cafe.

This optimistic, imaginative side to Baltimore is what Bedford – who thinks out of the box as a matter of course – wants to build on most of all at the BMA, bringing new fire to others who are already on the job. ‘Museums need to become physically and mentally more engaged in the needs of the city and the areas that are traditionally ignored. What I’m beginning to think about is the civic library model in the American city because it meets specific social needs – computers, social learning. We as museums need to assimilate those ideas.’ He sees the BMA’s financial constraints almost as a bonus: ‘I believe there is a tyranny of [the] limitless in some museums, whereas if you have limits then you use your imagination and somehow good things get done. When you have a good idea about helping new audiences, then new people who did not associate themselves with museums come forward.’ As for the renowned ‘tyranny’ of the American museum board, he calls his one ‘bold and brave… they want to achieve substantial and rapid change’ and are willing to trust him.

The Rabbit in the Hat (2009), Amy Sherald. Baltimore Museum of Art

Perhaps Bedford’s greatest gift to the BMA and Baltimore is his deep knowledge of contemporary African-American art. ‘I witnessed and knew the golden generation of African-American artists – Mark Bradford, its leading light, then there’s Theaster Gates, Rick Lowe, Mickalene Thomas and others.’ Having co-curated Mark Bradford’s installation ‘Tomorrow is Another Day’ to represent the US at the Venice Biennale in 2017, he brought it to the BMA last year and Bradford developed one of his innovative street studios in the city’s Greenmount West district – where much of The Wire was filmed – working with a community centre to give locals access to making art, to clothing, to security. ‘This silk screen-printing project brings both entities together in partnership, and both flourish,’ says Bedford. ‘Small amounts of money can effect great change. I notice this when I go to Tate in London: despite their enormity, they still have a rugged grass-roots ethic to serve the city.’ Bedford’s long friendship with Bradford has been inspirational: ‘Mark is my north-south of what I think an institution can be, one foot in the studio, one foot in the social world. In South LA, he started a not-for-profit in two blocks which he now owns, for programmes, artist spaces, transitional living.’

Back in the museum, Brooklyn-based artist Mickalene Thomas is the first recipient of the BMA’s new biennial commission for the two-storey lobby of the East Wing, which carries with it a fellowship for a qualified curator to gain museum experience. Funded by an endowment from Baltimore locals Robert Meyerhoff and Rheda Becker, this innovative idea will continue in perpetuity. Bedford believes Baltimore has a ‘great artistic ferment’ ready to be better recognised. On arrival, he did the rounds of artists’ studios and co-op spaces across the city, and especially in the Highlandtown, Station North and Bromo arts districts. Two African American artists he visited were Stephen Towns and Amy Sherald, now known for her portrait of Michelle Obama. Towns had a show at the BMA last year; Sherald has joined the museum’s board. ‘By connecting the museum to the international art world, we can make Baltimore artists international, too,’ Bedford says.

It’s just over two miles south along Charles Street from the BMA, next to Johns Hopkins University in Charles Village district, to the Walters Art Museum, set among the handsome terraces of Mount Vernon. Neighbours include the Peabody Institute (George Peabody made banking fortunes in Massachusetts, London and Baltimore), and the Enoch Pratt Free Library, as well as Pratt’s mansion, now occupied by the substantial Maryland Historical Society – Pratt, whom Andrew Carnegie credited with inspiring his own philanthropy, arrived in Baltimore in 1831 with $150 and made fortunes in railroads, coal and banking.

The Fisherman’s Cottage (1871), Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot. Walters Art Museum, Baltimore

Since the arrival of charismatic director Julia Marciari-Alexander in 2013, the Walters has been buzzing with imaginative change and fresh ideas. ‘I like to think of us as in a Gutenberg moment,’ she says, slightly alarmingly, then explains: ‘We are connecting the past, present and future… connecting objects and individuals who create conversations about humanity across time.’ She has an urgent desire to shake things up, to ‘use the collection almost as a laboratory of discovery’, while admitting that such radical change is ‘not going to happen coming out of the gate’.

The museum was founded by yet another Baltimore man with a belief in the social power of art and knowledge. Henry Walters (1848–1931) inherited the European and Asian art collected by his father William – while living in Paris he’d bought pictures by Daumier, Gérôme, Corot and Douanier Rousseau from George A. Lucas (a portrait of Lucas by Whistler hangs in the museum today). Henry Walters used his father’s Baltimore fortune, made from liquor, banking and railroads, to enlarge and broaden the collection, giving it a fashionable encyclopaedic character. Having welcomed the curious to see it in his townhouse, in 1909 he opened his purpose-built ‘palazzo’ museum nearby. On his death, he bequeathed the entire collection of more than 22,000 pieces, plus the palazzo, his townhouse and some of his fortune, to Baltimore city ‘for the benefit of the public’. Today, the collection has grown to 36,000 items, and the maze of galleries has expanded to occupy a building erected in 1974 and the elegant historic Hackerman House at 1 West Mount Vernon Place.

The newly completed restoration and rethink of Hackerman House excites Marciari-Alexander the most. ‘We treat our historical campus buildings as works of art. This 1850s mansion is a showpiece of architecture and design, one of the grandest buildings in Baltimore when it was built. We’ve restored it so that you are struck by it. All the rooms are used, but in a contemporary way.’ In one, historic Sèvres pieces from the museum’s exceptional ceramics collection are displayed near contemporary responses by Roberto Lugo – ceramicist, activist and poet, born to Puerto Rican immigrants up the coast in Philadelphia; the pieces were on show until July, but the museum has bought several of them. The library serves its original purpose, with table, chairs and screens to explore the collection and its background. A multi-year project is in train to put the collection’s fine manuscript holdings online so each can be read page by page. ‘We spent a lot of time and money figuring out a way to stitch the pages together,’ Marciari-Alexander says – the Walters’ conservation department, founded in 1934, is one of the oldest and most respected in the United States. Upstairs, one room has a single masterpiece and chairs to sit on, to encourage ‘slow art’ enjoyment; another looks at the colour red in ceramics; another tells the story of the people trading them. Then, a surprise: a room filled with 400 plates, each decorated by a Baltimore artist. ‘This has equal weight to our masterpieces,’ Marciari-Alexander says.

Seated Buddha (18th–19th century), Burmese. Walters Art Museum, Baltimore

Her priorities are clear across all her initiatives. ‘We are the embodiment of the private-public partnership,’ she says. ‘We have the city, corporations, individuals. We have an incredibly strong philanthropic tradition; Baltimore is such an old city, people know that in order to have a thriving city in all aspects, you have to have culture. This is understood.’ The renovated Asian galleries, reopened in 2017 in a dramatic display, illustrate this: building on Henry Walters’ buys and anchored by part of the collection of the tobacco heiress Doris Duke (1912–93), together with big gifts from locals John and Berthe Ford (South Asia), Alexander Brown Griswold (Thai) and Betsy and Robert Feinberg (contemporary Japanese ceramics), this is one of North America’s finest holdings of Asian art.

Marciari-Alexander wants to ‘create moments of wonder [for visitors] from all backgrounds. I want them to have anger, too, whatever emotions they have, and to take this and think about how they connect with Baltimore.’ With this in mind, to lure the city’s fastest-growing community, Latinx (the gender-neutral alternative to Latino), into the museum, she has dusted down some ancient objects from western Mexico and Guatemala that have not been on show for some time.

Portrait head (550–850), Campeche, Mexico. Walters Art Museum, Baltimore

Marciari-Alexander speaks in tune with Chris Bedford when she says: ‘We don’t do anything in isolation. Our whole vision is to augment the strength of the city. The constellation of speciality collections makes this one of the more exceptional cultural cities in the US – along with Cleveland, Detroit, Toledo, Pittsburgh.’ She pauses, then smiles confidently. ‘They have one landmark museum. We have two.’ She and Bedford are putting Baltimore on the world museum stage in new ways that include the people of Baltimore, blazing a trail for others to follow.

This is an updated version of an article from the March 2019 issue of Apollo. Preview the current issue and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home