Around 1939, a highly distinctive group of stone sculptures appeared on the French art market. In Paris, Charles Ratton, the great dealer and promoter of ‘arts primitifs’, drew some to the attention of the Swiss collector Josef Müller, who was already adding ethnographic art to a remarkable collection of paintings by the likes of Cézanne, Matisse, Picasso and Braque. From the antiques dealer Madame Vignier, Müller acquired seven of these sculptures, Ratton three. (Henri-Pierre Roché – who introduced Gertrude Stein to Picasso, and later wrote the novel Jules et Jim – also acquired three when more appeared on the market in the following years.) Vignier claimed they were ‘Celtic’ statues from the Vendée in western France, but did not seem to be very sure.

As Paris began mobilising for war, Müller returned to Switzerland, leaving these granite and volcanic-rock curiosities behind in the safekeeping of the Japanese cabinetmaker Kichizo Inagaki – known for making stands for ethnographic artworks, as well as furniture for the designer Eileen Gray. In 1945, Ratton showed the sculptures to the then little-known Jean Dubuffet, an artist looking to forge a new kind of ‘raw’, anti-intellectual art. Dubuffet wrote to Müller immediately, asking permission to have them photographed for the first of a planned series of booklets on what he termed Art Brut. As he explained in his letter, he was interested in ‘certain isolated, instinctive and delirious forms of folk art’ and had for some time been researching the subject. Other examples of these stone heads had come to light – one, for instance, had been in the museum of natural history in Lyon since 1934. Convinced they were the work of a single, self-taught ‘outsider’ artist, Dubuffet published 16 pieces and dubbed them ‘Les Barbus Müller’, despite the fact that only some of the heads sport beards. He also exhibited them at the inaugural show of the Foyer de l’Art Brut in Paris in 1947.

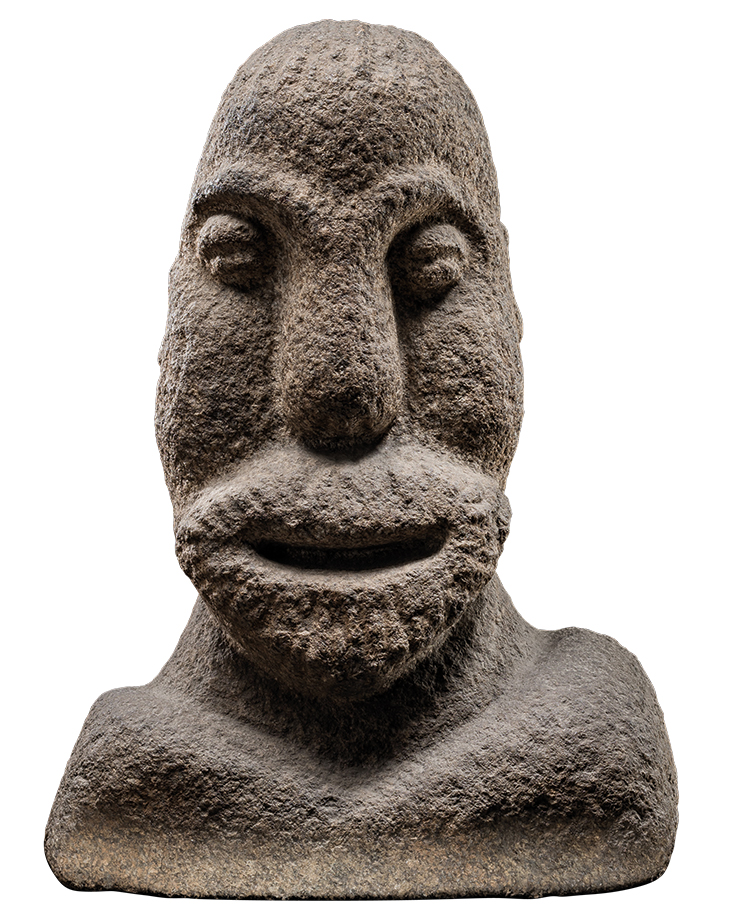

‘Barbu Müller’ sculpture (late 19th–early 20th century), attrib. Antoine Rabany. Musée Barbier-Mueller, Geneva. Photo: Luis Lourenço

The name stuck, one constant in a changing landscape of attempted identification and classification. It was variously suggested that these sculptures might be from the Marquesas Islands in French Polynesia, or from the Taíno culture of the Caribbean, or even that they were faux-Romanesque sculptures. (Ratton – rightly, as later analysis revealed – always assumed they must be from the Auvergne region.) In 1979, the recently opened Musée Barbier-Mueller in Geneva, founded by Josef’s daughter Monique and her husband Jean Paul Barbier, exhibited ‘Les Barbus Müller’ and published a facsimile of the Dubuffet booklet which, although printed by the esteemed publisher Gallimard and containing the founding manifesto of Art Brut, had never been distributed. It was in this Swiss museum, serendipitously, that the writer, artist and champion of outsider art Bruno Montpied bought a copy of the booklet in 1980. When in 2017 his editor drew his attention to prints from two glass-plate photographs for sale on the internet, he knew exactly what he was looking at. Here was a rustic vegetable garden full of figures uncannily like those ‘bearded men’, placed atop ‘totems’ of stacked round stones.

Better yet, the images showed not only a distinctive thatched hut in the garden but also enough of the landscape to identify in the background the 10th-century chapel of the cemetery of Chambon-sur-Lac in the Auvergne. Montpied’s patient detective work led him to the plot intact, and its ownership at the time of the 1911 census; it was around then, he later learned, that some of these Chambon sculptures were discovered and published in an archaeological journal as forgeries of Romanesque carvings. Among them was the cover piece of Dubuffet’s catalogue. The so-called Barbus Müller, it transpired, were the work of a peasant farmer named Antoine Rabany (1844–1919), known as ‘the Zouave’ after serving in the French army in North Africa. Perhaps he drew inspiration from what he saw there, as well as from the roughly hewn figures on the portal of the nearby cemetery chapel.

‘Barbu Müller’ sculpture (late 19th–early 20th century), attrib. Antoine Rabany. Musée Barbier-Mueller, Geneva. Photo: Luis Lourenço

An exhibition at the Musée Barbier-Mueller brings together 18 of the 40 known ‘Barbus Müller’ – not all of which are definitely by Rabany – and associated documentation (Dubuffet’s booklet has been reprinted as a catalogue insert). Shown alongside them are seven works by Dubuffet, and stone sculptures from across the globe – Celtic, Taíno, Cochiti, Sapi, Ethiopian, Sepik. Together they illuminate a particular moment in Europe that drew together interest in indigenous cultures, outsider art and the avant-garde.

‘Les Barbus Müller’ is at the Musée Barbier-Mueller, Geneva, until 1 November.

From the July/August issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home