Beauford Delaney (1901–79) – great painter of cityscapes, portraits, and works of Abstract Expressionism – is at last ascending as his friend the writer James Baldwin thought he might. ‘Beauford Delaney and James Baldwin: Through the Unusual Door’, curated by Stephen Wicks, opened in February at the Knoxville Museum of Art. Due to the patient work of Wicks and many others over decades, Knoxville, where Delaney grew up, now has the largest institutional holding of his work in the world, and the show is luminous and revealing.

When I started to write about Delaney’s long friendship with James Baldwin for my book A Chance Meeting, 18 years ago, I had not yet been in the presence of his paintings. Since then, I have studied a handful of Delaneys, with a growing feeling of his significance: here was a man who could do whatever interested him in paint. Reproductions undermine different artists in different ways. What goes missing from Delaney’s paintings are: effects of depth, transparency, and opacity; the wittiness of his juxtapositions and cropping; and the extreme freedom of his brushstrokes. It made an enormous difference in my understanding to take part in a recent symposium in Knoxville of scholars thinking about Delaney and Baldwin, and to spend hours in the exhibition there. James Baldwin was not wrong when he said of his dear friend and mentor, ‘He is a great painter, among the very greatest.’

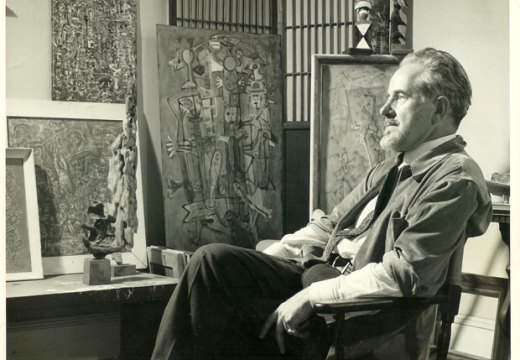

Self-Portrait (1962), Beauford Delaney. Collection of Halley K Harrisburg and Michael Rosenfeld, New York. Courtesy Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York; © Estate of Beauford Delaney, by permission of Derek L. Spratley, Esquire, Court Appointed Administrator

Look, for example, at a brilliantly original self-portrait of Delaney in blue-black-yellow and a beret, against a red-orange background, the whole integrated by a swirling abstract yellow pattern. Standing in front of this painting, I saw something of how Delaney thought of Rembrandt, of the use of colour in Sam Francis (a friend of Delaney’s), of the landscapes of John Marin and Marsden Hartley (whose works Delaney knew through his friendship with Alfred Stieglitz and Georgia O’Keeffe), and of the work of both Elaine and Willem De Kooning. Delaney knew the De Koonings, too, and Elaine De Kooning reviewed a painting of his in Art News, in February 1949, at a key moment in the development of Abstract Expressionism, praising Delaney’s ‘abstractly conceived’ Snow Scene for its ‘style, mood […] boldness of [impasto] technique’ and for its ‘startling colors’.

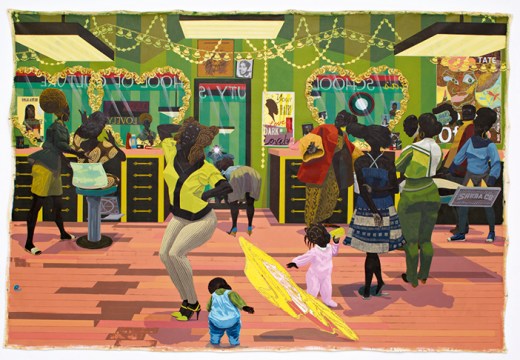

Beauford Delaney grew up in segregated Knoxville. His father was a preacher and the household was an educated, musical one, but poverty and racism meant that, of the ten children in the family, only three brothers survived into adulthood – the other children died, often of treatable diseases, at six, in infancy, at 19. Beauford and his younger brother Joseph, who would also become a painter, found people who were willing to teach them, and found ways north to Boston and New York in the 1920s. Delaney moved to Paris in 1953, in part to be near Baldwin, and remained in France until his death. He lived in poverty, and was an extremely generous man, giving away whatever money came to him, and acting as mentor and guide to many. Baldwin and others in turn supported him sometimes financially, and doing what else they could, when Delaney, suffering from mental illness, heard voices that attacked him for his race and his sexual orientation. Delaney had shows and gallerists; he sold works, but not very many. He did not start and stop in convenient periods, or follow a linear development. He resisted the imposed distinctions between abstraction and figuration, between figure and ground, even between surface and depth. Delaney’s work is difficult, and goes on being stimulating and relevant for artists working now. Glenn Ligon, who curated the show ‘Encounters and Collisions’ in 2015 wrote a catalogue essay in the form of a letter addressed to Delaney: ‘in your paintings, the line between figuration and abstraction is always porous. That has inspired a similar fluidity in my paintings, which often turn text (a kind of figuration, I suppose) toward abstraction.’

Delaney used to say that he worked his paintings up, inscribing and overpainting, revisiting and reinterpreting, often over years. He loved the work of Charlie Parker, Ella Fitzgerald, W.C. Handy, Bessie Smith, Marian Anderson, and many other blues and jazz musicians, whom he listened to on his Victrola every day, and often heard live. As jazz musicians rework a standard or a quotation from another musician, Delaney redid his works, and quoted the brushwork of other artists and artistic traditions. In 1966, the year of the death of Giacometti, whom he also knew, Delaney painted James Baldwin à la Giacometti, against the variable yellow background that was Delaney’s blend of radiance and anguish. In his notebooks and watercolours, day after day, with meditative seriousness, he worked at what he called his own ‘calligraphy’ referring, it seems, to a long-standing interest in Asian art, including that of his friend, the Korean painter Yi Eungro, with whom Delaney shared a gallerist in Paris.

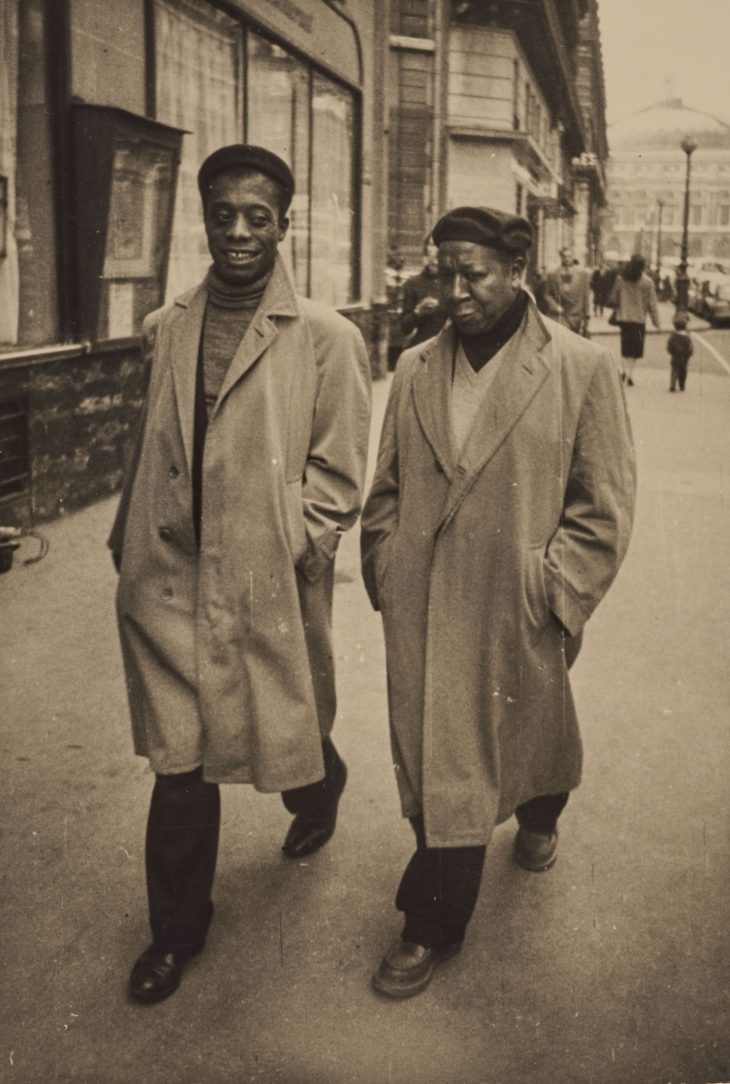

Photograph of James Baldwin and Beauford Delaney in Paris, c. 1960. Estate of Beauford Delaney

At the symposium, I spoke about some similarities between the ways in which Delaney paints two oval forms – the eyes in his portraits, and the puddles in the streetscapes he painted of Greenwich village in the 1940s. These are wet, reflective surfaces, like paintings themselves, in which colours change and merge, in which layers of surface and depth get mingled, that can contain both inward worlds and interpretations of outward worlds. Other speakers discussed openings, the ‘unusual door’ from the old spiritual that Baldwin and Delaney both liked to refer to, and the window at Delaney’s studio in Clamart, Paris, before which he would sit for many hours, sometimes lonely, sometimes tranquil, a window that he and Baldwin both understood as a key to his movement into abstract works, what Baldwin called ‘a most striking metamorphosis into freedom’.

In the wide first room of the exhibition at Knoxville, Stephen Wicks has made what he calls ‘a Clamart chapel’ with a wonderful sequence of the abstract paintings and watercolours. Like the Rothko chapel at the Menil Collection, and like the stained-glass spaces at Chartres that Delaney loved, it is a place where quiet holds motion within stillness. In the hush of the gallery, standing near two self-portraits and looking across to the Clamart chapel, I said to Stephen Wicks that I was still struggling to name the relationship between the surfaces and the depths in Delaney. Like passageways, I said. Like doors, he said. Yes, I said, but a door can be an obstruction, a slab, this is more like an open doorway. Like a threshold, he said. A difficult word, with a history of labour, the space next to a house where a person fights with a mass of lines for the grains of survival. Also, in its sound, in the deference and hope with which it approaches what lies beyond, a beautiful word.

The Knoxville Museum of Art is temporarily closed due to the Covid-19 outbreak. For more information about ‘Beauford Delaney and James Baldwin: Through the Unusual Door’, visit the institution’s website.

From the April 2020 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home