The Royal Academy of Arts’ ‘Bill Viola/Michelangelo’ exhibition is explicitly framed not as a comparison but as a ‘conversation’. The aim is to explore the thematic similarities between Viola’s immersive video and sound installations and a group of drawings by Michelangelo. The works on display invite contemplation of life and death, mortality and the soul. Despite the centuries that divide them, Michelangelo and Viola share the conviction that when grappling with the big questions – why are we here, what does it all mean, what happens next – we should turn to art.

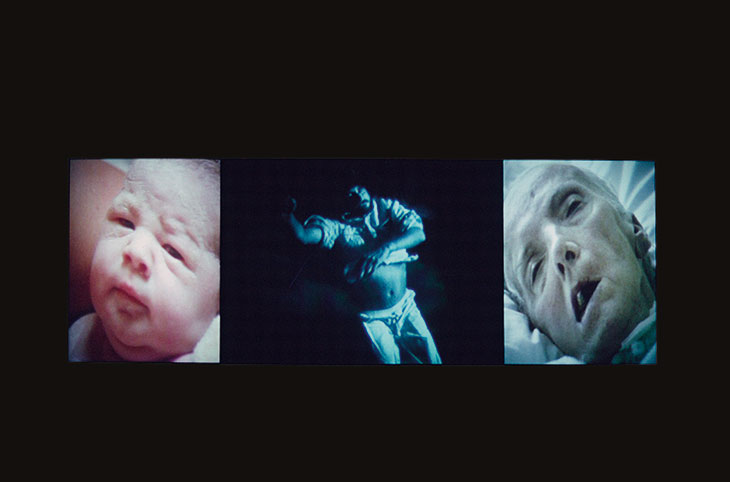

The pairing is at times illuminating. Early on, we encounter Viola’s Nantes Triptych (1992) alongside Michelangelo works (three drawings from the 1530s–40s and the Taddei Tondo) featuring the Virgin and Christ. The Triptych is formed of three video screens: in one a child is born, in another the life of an elderly woman (Viola’s mother) slips away as her child holds her hand. It is undeniably affecting to watch these experiences, at once so ordinary and utterly extraordinary, taking place in tandem. The soundtrack of the labouring mother’s cries and a heaving respirator provides the backdrop to contemplation of the Michelangelo works. Here, the physical bond between mother and child, whether he is a wriggly infant with chubby thighs or a naked, lifeless adult, is tenderly rendered. The Virgin’s unbearable foreknowledge of her son’s death is underlined: she reaches out to shield him from a playfully proffered goldfinch (its red plumage symbolising his future bloodshed); she bears his dead form between her legs in an echo of his birth. The disruption of the natural order playing out on Viola’s screens – with the child offering comfort and easing the parent’s passing from this life – is painfully felt.

The Virgin and Child with the Infant St John, known as the Taddei Tondo (c. 1504–05), Michelangelo Buonarroti. Royal Academy of Arts, London. Photo: Prudence Cuming Associates Limited

The central screen of the Nantes Triptych, which occupies the place of greatest importance in this video altarpiece, is the least engaging. We see a man submerged in water, a motif repeated throughout Viola’s work in the exhibition. Video after video invites meditation on the transformative power of water, in which our bodies become weightless, suspended between different states of being. The Royal Academy galleries certainly provide a fitting space for the dramatic Five Angels of the Millennium (2001), in which water undulates, figures plunge and bubbles ripple in five huge projections lining a darkened room. But by the third or fourth portentous encounter with someone bobbing about in a pool it begins to wear a bit thin.

Nantes Triptych (1992), Bill Viola. Photo: Kira Perov. Courtesy Bill Viola Studio

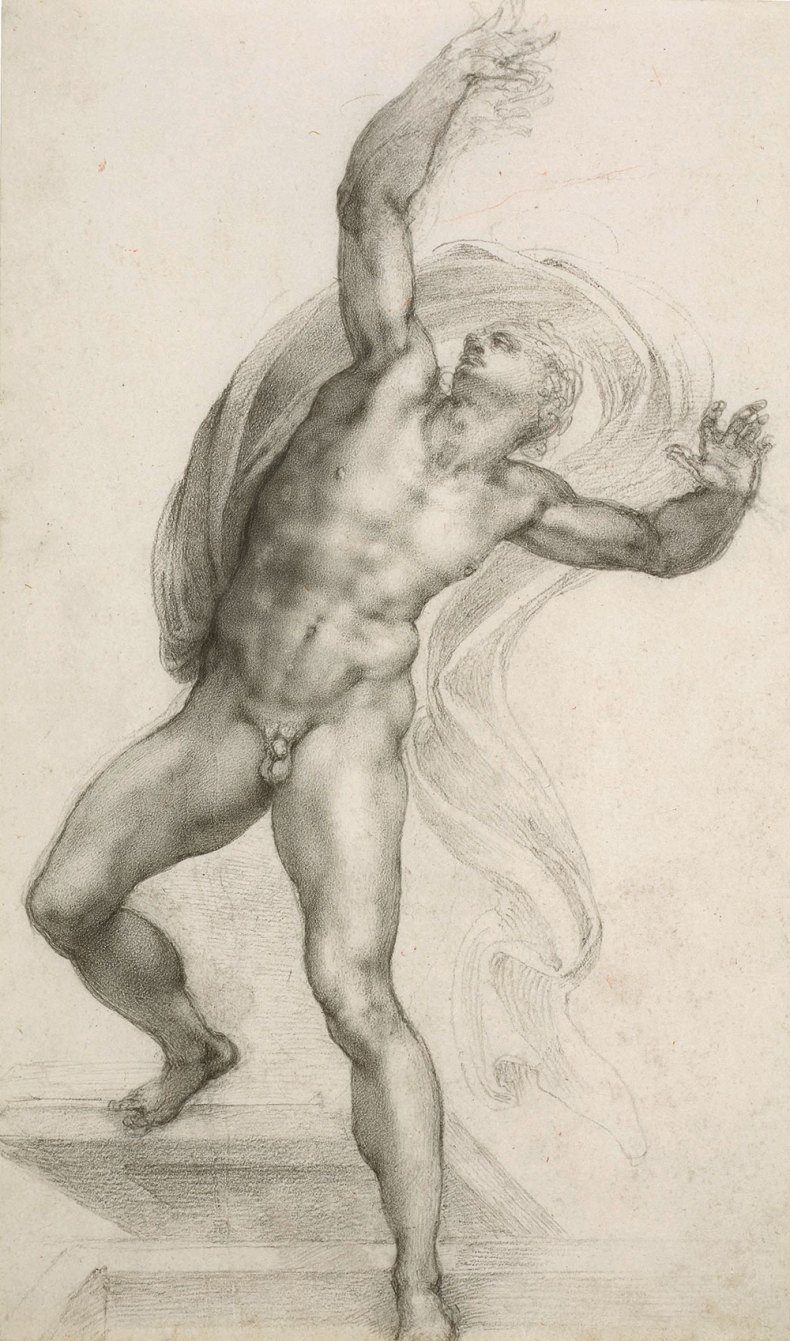

The unavoidable problem is that despite the invitation to consider a thematic ‘relationship’ between the exhibition’s two protagonists, this does inevitably involve comparison. By this measure, Viola comes up woefully short. In later rooms, from Michelangelo we get wrenching and profound meditations as he wrestles with his erotic impulses, perceived sinfulness and comprehension of the Christian mysteries. The artist was deeply engaged with Renaissance Neoplatonism, and its paradoxical insistence that physical beauty could prompt the ascent of the soul informs drawings of the Resurrection made in the 1530s. In these, Christ’s form is radiant, vital and firmly outlined, larger than any of the figures around him: the miracle of redemption is made manifest in his perfect body. This is drawing as an urgent act of faith, culminating in images of the Crucifixion, produced when Michelangelo was in his mid eighties, in which the boundaries of Christ and the cross are dissolved in an effort to get to the heart of their spiritual truth. These are some of the most personal and powerful images in Western art. Displayed alongside them Viola’s Surrender (2001), in which a man and woman plunge their heads into water, looks silly and conceptually insubstantial.

The Risen Christ (c. 1532–33), Michelangelo Buonarroti. Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2018

Viola is a popular artist, and it would be churlish to deny that his work is capable of moving people spiritually. But while on their own terms his video installations can be thought-provoking and visually striking (if somewhat grandiose), here a paucity of ideas is exposed. It is largely despite Viola, then, that I urge you to visit this exhibition. Michelangelo’s drawings, particularly the late ones gathered in the penultimate room, are extraordinary. They may not be shown together again for many years, and the opportunity to see them should not be missed.

‘Bill Viola/Michelangelo: Life Death Rebirth’ is at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, until 31 March.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home