From the June issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here

Eric Ravilious

1 April–31 August 2015

Dulwich Picture Gallery, London

—

Catalogue by James Russell

ISBN 9781781300329 (paperback), £25 (Dulwich Picture Gallery and Philip Wilson Publishers Ltd)

Eric Ravilious (1903–42) was not the sort of artist who made headlines. Despite having a couple of mistresses, he was no Augustus John; though he lived through the turbulent decades of the 1920s and ’30s, he was not a political painter; nor was he an abstractionist or a surrealist when these movements were at their height in Britain. To his friends he was simply ‘The Boy’, and other than a few brief pre-war trips to Italy and France he passed most of his short life in the south-east of England, getting on quietly with the job of making beautiful things: wood-engravings, book illustrations, murals, ceramic and textile designs for Wedgwood and Dunbar Hay and, increasingly as he got older, watercolours.

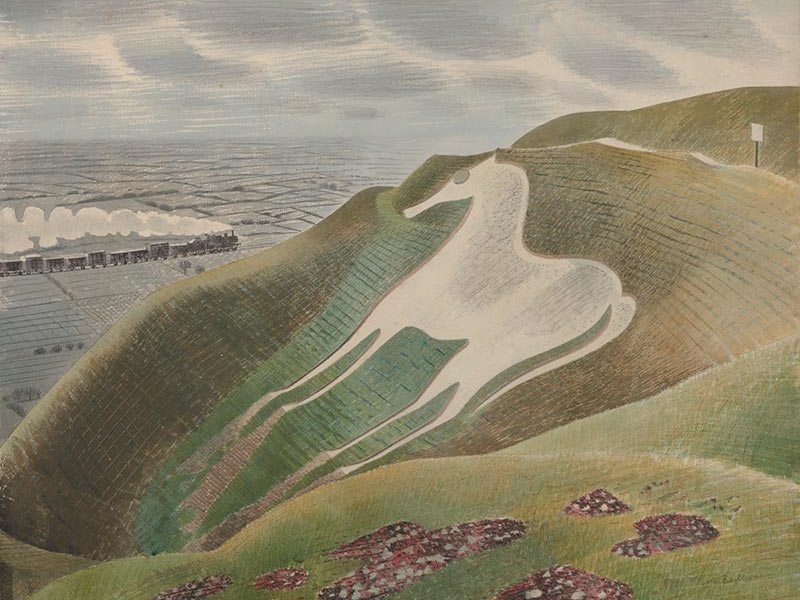

Ravilious quite caught the eye last autumn, however, when his 1938 painting Bathing Machines, Aldeburgh, sold at auction for a little over a quarter of a million pounds. That painting is among the 70 or so works now on exhibit at Dulwich Picture Gallery. It is understated, unremarkable even, but it captures a nostalgia for a lost England and a way of life that even then was fading away. And it is all the more evocative because the best of Ravilious’s work – Tea at Furlongs (1939), or the series of chalk Downland figures – came on the eve of the war that would kill him.

The remarkable price fetched by his Suffolk bathing machines, together with this exhibition, mark the re-arrival in the popular consciousness of this underappreciated, yet significant, and very English artist. Ravilious’s re-emergence has been underway for over a decade. In 2003 there was the large centenary exhibition at the Imperial War Museum, curated by Alan Powers – a success Powers followed up 10 years later with his comprehensive critical biography devoted to all aspects of Ravilious’s extensive oeuvre. Also steadily banging the drum for Ravilious over recent years has been James Russell, whose series of eye-catching monographs published by the Mainstone Press has reproduced many of Ravilious’s best pictures.

It is appropriate therefore that Russell, as one of the two leading Ravilious scholars, is the curator of this new show. With the assistance of the artist’s daughter, Anne Ullmann, Russell has chosen to focus almost exclusively on the watercolours. And rather than following a chronological approach, he has arranged the works into a series of six thematically arranged galleries.

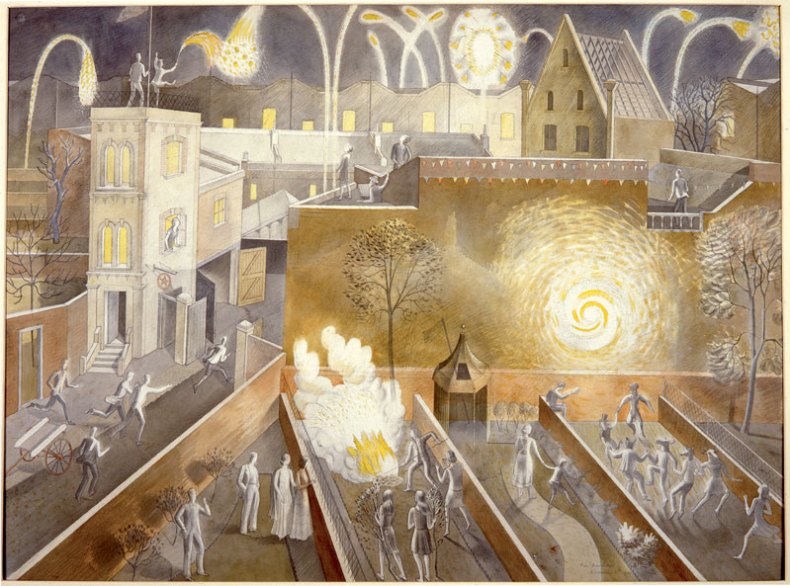

In some ways this is a shame. As Russell explains in his focused and beautifully illustrated catalogue, Ravilious’s precocious ability as a wood engraver informed his unusual and experimental techniques as a watercolourist – as did his subsequent work as a lithographer in the 1930s. As a student at the Royal College of Art in the early 1920s – where his contemporaries included Edward Bawden and Henry Moore – Ravilious’s scholarship had been in the Design School. One of his first commissions after he graduated was a series of murals at Morley College, in London. These were followed by another set of murals at the recently completed Midland Hotel in Morecambe, Lancashire. Sadly, due to the interventions of war and weather, neither of these youthful achievements survives. Something of them however is to be seen in the large 1933 watercolour, November 5th. Due to Russell’s thematic approach, this work appears in the final gallery of the exhibition, whereas it might have been better placed nearer the beginning.

Like the paintings of Paul Nash, who taught him briefly at the RCA, Ravilious’s watercolours tend to be devoid of figures. This, though, is not true of November 5th. Here figures dance in gardens or rush to rooftops to watch a wondrous display of fireworks. There is a playful mysteriousness about this painting. Ravilious is fascinated not only by the people, but also by the play of light and shadow, by the architectural shapes and spaces. (Inexplicably, the tiles from the roof of one building are missing, allowing a glimpse into its eerie attics.)

As the people vanish from Ravilious’s watercolours, their presence is never entirely lost. Yet so often these paintings feel empty: the buildings and river boats are deserted, the Downland fields he so loved are frequently abandoned; bedrooms lie unoccupied, and a table set for tea in the garden is as inexplicably deserted as the Mary Celeste. Does this point to some turmoil in the artist’s inner life?

The contemporary artist Ravilious most resembles is Stanley Spencer: the woman beating the carpet in Prospect from an Attic (1932) could easily have come from a Spencer painting. Both artists shared an almost obsessive attention to detail – be it a wooden fence, a string of barbed wire or a wall of bricks; in both, the mundane can become almost mystical. And both were born to an eccentric father with a religious preoccupation. Stanley Spencer rarely stopped talking and writing about his work; Ravilious bottled it all up.

That the life of this quietly fascinating artist was cut so brutally short was a tragedy. Ravilious died in 1942, aged 39. He had only just arrived in Iceland as an official war artist when a plane he was travelling in vanished on a sea-rescue mission. Though the war provided the subject for most of Ravilious’s final paintings, its looming threat was something he had largely ignored in the years. In 1937, Ravilious had helped make designs for the British Pavilion at the Paris International Exposition. While the Spanish exhibited Picasso’s Guernica and the Germans and Russians erected immense towers to Nazism and Socialism, the British promoted tea and tennis. ‘It is certain,’ the foreword to the guide to the British Pavilion pointed out ‘that no civilised life is possible which does not, as part of its business and justification, aim at enjoyment’. At a time of strife, Ravilious’s paintings were an embodiment of civilisation – beautiful things to be both enjoyed and puzzled over. In a world again ill at ease with itself, this remains part of their importance.

David Boyd Haycock is the author of A Crisis of Brilliance (Old Street Publishing).

Click here to buy the latest issue of Apollo

Related Articles

‘Another Life, Another World’: Paul Nash’s watercolours

New Horizons: British art and flight

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home