The current crisis at the British Museum has something for every kind of critic, and there are many, of the institution. A museum that admits that some 2,000 objects are missing, thought to be stolen, is admitting a failure of its most basic purpose: to look after all the items in its care. That it is the British Museum that has failed has invited a good deal of Schadenfreude – some private, much not – from those both outside and perhaps even inside the museum. The museum’s annual report for 2021–22, for example, began with its new chair of trustees, George Osborne, declaring that ‘The British Museum is firing on all cylinders.’ If only this were true.

To recap recent events: on 28 July, the museum’s director Hartwig Fischer announced that he was stepping down in 2024. On 16 August, the museum issued a press release saying that a member of staff had been sacked on suspicion of stealing and selling artefacts from the collection. On 25 August, Fischer announced that he was resigning immediately, or as soon as an interim director could be found. He also withdrew earlier remarks regretting that the dealer who had alerted the museum to items turning up for sale had not revealed the full extent of his suspicions. The criminal investigation of what exactly has been stolen, by whom and over what period of time is now a matter for the police. The wider investigation into what has gone wrong is a matter for everyone who believes in public museums and involves some decidedly unexciting questions about the running of the British Museum.

Most of the reporting of the museum’s woes has mentioned that the institution is working on a ‘Masterplan’ for the complete refurbishment of the building and a full redisplay of the collection – to cost hundreds of millions of pounds over several decades. It is hard to see how any masterplan – expected in spring this year, then postponed to autumn – can progress without a new permanent director in place. It is, however, indicative of some kind of failure that the British Museum has not published a strategic plan since 2014, i.e. under its previous director – and that was called ‘Towards 2020’. (For comparison, most national museums updated their existing strategic plans in 2021/22 or wrote plans just before the pandemic that run up to 2030.) The BM is the only major national museum not to have a current document – and it is unclear why the trustees or the Department of Culture, Media and Sport have allowed this to be the case.

The British Museum is so big an institution that it will inevitably flounder without a clearly communicated set of priorities and careful oversight. On the subject of restitution, for instance, for too long the museum has hidden behind the British Museum Act of 1963 as an excuse not to discuss it. The failure of the directorate to have much of anything to say about the Parthenon Marbles, Benin Bronzes and Ethiopian tabots (three very different categories of objects that could be dealt with in very different ways) has been highlighted by the arrival of George Osborne as chair of the board of trustees.

Since September 2021, Osborne has been the museum’s most public voice (its only public voice, some might say) and seems to be relishing negotiations with the Greek government over the Parthenon Marbles. But if it is the director of the museum ‘who is responsible to the Trustees for the care of all the property in their possession and for the general administration of the Museum’, this raises the question of who a vocal chair of trustees answers to – and who is really in charge. (And will that chair be more retiring if a less reticent director is appointed?) And when a longstanding deputy director ‘steps back’ from his duties instead of stepping in for his director, the internal failure seems greater still. Moreover, should an internal investigation be called ‘an independent review’ when it is co-conducted by a former deputy chair of the trustees who also sat on the audit committee assessing risks to the museum?

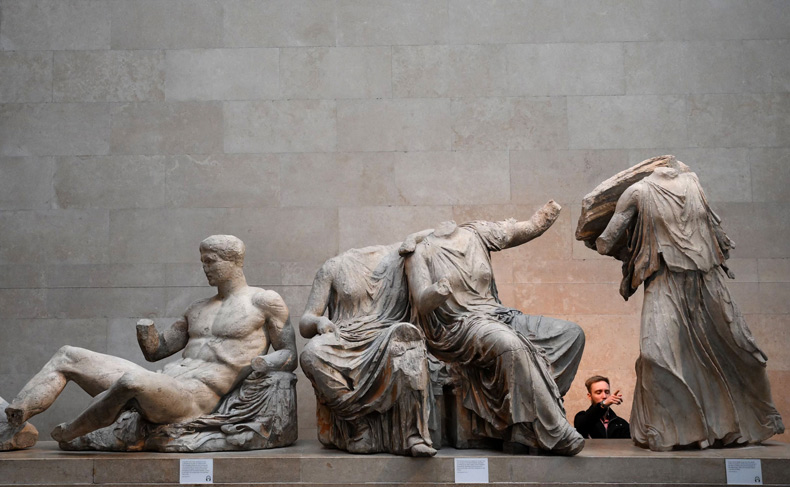

Losing whose marbles? Statues from the east pediment of the Parthenon at the British Museum. Photo: DANIEL LEAL/AFP via Getty Images

The British Museum is a Rorschach blot of a crisis. Critics of the ‘rewriting of history’ (as if history is not something to be endlessly rewritten and expanded) can point to the neglect of basic collection care. Critics of the museum’s ostrich-like approach to restitution can say that the British Museum has even less of a claim to the most obviously looted objects it owns. Critics of free admission can say that museums need the income from charging (ignoring other drops in income that would follow). And critics of George Osborne’s decisions as Chancellor of Exchequer can point to the awkwardness of him rushing to the rescue of the world’s first public and national museum. (When the Egyptian writer Ahdaf Soueif resigned from the board of trustees in 2019, she cited as factors the refusal to discuss difficult topics: sponsorship by BP, the contracting-out of staff, and restitution. In the plus column, she put the expertise of the museum’s own curators, its research and initiatives to train curators around the world and to track stolen artefacts – stolen outside the museum, that is. All of this seems right.)

If you walk through as much of the British Museum as you can manage, as I did last week, you will come away feeling overwhelmed – and depressed by some of the long-neglected and less-visited galleries (the Greek and Roman galleries on the Upper Floor might be the outstanding example). Thinking about what remains in storage, how much of that is still to be catalogued as inventory and, crucially, who is going to pay for it is more overwhelming still.

In the short term and seen from the outside, the appointment of Mark Jones, formerly of the Victoria and Albert Museum and National Museums Scotland, as interim director seems sensible. For morale inside the museum, the appointment of the well-respected and well-liked Carl Heron as acting deputy director will come as a relief. The museum’s annual report for 2022–23 is now available. Completed in March, it necessarily contains no reference to recent events, but the introduction ends with a statement of intent from George Osborne: ‘It’s a year of action.’ It certainly will be. In the long term, however, the solutions are going to be slow and unflashy, however urgently they are needed.

Who should fix the crisis at the British Museum?

The Great Court of the British Museum in August 2023. Photo: Leon Neal/Getty Images

Share

The current crisis at the British Museum has something for every kind of critic, and there are many, of the institution. A museum that admits that some 2,000 objects are missing, thought to be stolen, is admitting a failure of its most basic purpose: to look after all the items in its care. That it is the British Museum that has failed has invited a good deal of Schadenfreude – some private, much not – from those both outside and perhaps even inside the museum. The museum’s annual report for 2021–22, for example, began with its new chair of trustees, George Osborne, declaring that ‘The British Museum is firing on all cylinders.’ If only this were true.

To recap recent events: on 28 July, the museum’s director Hartwig Fischer announced that he was stepping down in 2024. On 16 August, the museum issued a press release saying that a member of staff had been sacked on suspicion of stealing and selling artefacts from the collection. On 25 August, Fischer announced that he was resigning immediately, or as soon as an interim director could be found. He also withdrew earlier remarks regretting that the dealer who had alerted the museum to items turning up for sale had not revealed the full extent of his suspicions. The criminal investigation of what exactly has been stolen, by whom and over what period of time is now a matter for the police. The wider investigation into what has gone wrong is a matter for everyone who believes in public museums and involves some decidedly unexciting questions about the running of the British Museum.

Most of the reporting of the museum’s woes has mentioned that the institution is working on a ‘Masterplan’ for the complete refurbishment of the building and a full redisplay of the collection – to cost hundreds of millions of pounds over several decades. It is hard to see how any masterplan – expected in spring this year, then postponed to autumn – can progress without a new permanent director in place. It is, however, indicative of some kind of failure that the British Museum has not published a strategic plan since 2014, i.e. under its previous director – and that was called ‘Towards 2020’. (For comparison, most national museums updated their existing strategic plans in 2021/22 or wrote plans just before the pandemic that run up to 2030.) The BM is the only major national museum not to have a current document – and it is unclear why the trustees or the Department of Culture, Media and Sport have allowed this to be the case.

The British Museum is so big an institution that it will inevitably flounder without a clearly communicated set of priorities and careful oversight. On the subject of restitution, for instance, for too long the museum has hidden behind the British Museum Act of 1963 as an excuse not to discuss it. The failure of the directorate to have much of anything to say about the Parthenon Marbles, Benin Bronzes and Ethiopian tabots (three very different categories of objects that could be dealt with in very different ways) has been highlighted by the arrival of George Osborne as chair of the board of trustees.

Since September 2021, Osborne has been the museum’s most public voice (its only public voice, some might say) and seems to be relishing negotiations with the Greek government over the Parthenon Marbles. But if it is the director of the museum ‘who is responsible to the Trustees for the care of all the property in their possession and for the general administration of the Museum’, this raises the question of who a vocal chair of trustees answers to – and who is really in charge. (And will that chair be more retiring if a less reticent director is appointed?) And when a longstanding deputy director ‘steps back’ from his duties instead of stepping in for his director, the internal failure seems greater still. Moreover, should an internal investigation be called ‘an independent review’ when it is co-conducted by a former deputy chair of the trustees who also sat on the audit committee assessing risks to the museum?

Losing whose marbles? Statues from the east pediment of the Parthenon at the British Museum. Photo: DANIEL LEAL/AFP via Getty Images

The British Museum is a Rorschach blot of a crisis. Critics of the ‘rewriting of history’ (as if history is not something to be endlessly rewritten and expanded) can point to the neglect of basic collection care. Critics of the museum’s ostrich-like approach to restitution can say that the British Museum has even less of a claim to the most obviously looted objects it owns. Critics of free admission can say that museums need the income from charging (ignoring other drops in income that would follow). And critics of George Osborne’s decisions as Chancellor of Exchequer can point to the awkwardness of him rushing to the rescue of the world’s first public and national museum. (When the Egyptian writer Ahdaf Soueif resigned from the board of trustees in 2019, she cited as factors the refusal to discuss difficult topics: sponsorship by BP, the contracting-out of staff, and restitution. In the plus column, she put the expertise of the museum’s own curators, its research and initiatives to train curators around the world and to track stolen artefacts – stolen outside the museum, that is. All of this seems right.)

If you walk through as much of the British Museum as you can manage, as I did last week, you will come away feeling overwhelmed – and depressed by some of the long-neglected and less-visited galleries (the Greek and Roman galleries on the Upper Floor might be the outstanding example). Thinking about what remains in storage, how much of that is still to be catalogued as inventory and, crucially, who is going to pay for it is more overwhelming still.

In the short term and seen from the outside, the appointment of Mark Jones, formerly of the Victoria and Albert Museum and National Museums Scotland, as interim director seems sensible. For morale inside the museum, the appointment of the well-respected and well-liked Carl Heron as acting deputy director will come as a relief. The museum’s annual report for 2022–23 is now available. Completed in March, it necessarily contains no reference to recent events, but the introduction ends with a statement of intent from George Osborne: ‘It’s a year of action.’ It certainly will be. In the long term, however, the solutions are going to be slow and unflashy, however urgently they are needed.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

Share

Recommended for you

We need a fair and formal process for restitution claims – but what would that look like?

As calls grow for the return of objects acquired during the colonial era, the assessment of claims requires an independent process

Are frictions in Nigeria jeopardising the return of the Benin Bronzes?

With cracks appearing in the relationships of institutions in Nigeria, Barnaby Phillips wonders where the returned Benin Bronzes are going to end up

Can the British Museum learn from The Lord of the Rings?

Given J.R.R. Tolkien’s apparent attitude to cultural property, the British Museum made an interesting venue for ‘The Rings of Power’ launch party