The long curling fingers of a ‘digitated’ lemon sit alongside chains worn by early Christian martyrs. The breastplate of an ancient Samnite warrior is next to a furry African civet, whose anus is angled awkwardly towards the viewer to emphasise the creature’s special musk, valuable in Renaissance perfume and medicine. Beside a large, detailed drawing showing an imaginary reconstruction of a Roman public banquet stands a morose-looking maned sloth, its implausibly strong and straight limbs holding up this beast, normally found hanging from the branch of a tree.

Fingered lemon (Citrus limon) (c. 1640), Vincenzo Leonardi. Royal Collection Trust; © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, 2019

These are all drawings from the Museo Cartaceo (‘paper museum’) assembled by the scholar and collector Cassiano dal Pozzo and his brother Carlo Antonio in Rome in the 17th century, and currently on display at the Barber Institute of Fine Arts in Birmingham. Comprising about 10,000 drawings, watercolours and prints, their paper museum was the dal Pozzos’ attempt to gather the most up-to-date knowledge of the natural world and classical antiquity into a single visual collection. Images were both collected and commissioned, brought together in a series of bound volumes housed in their library. The museum crossed all modern boundaries between art, science, religion and history, all united by the same interest in detailed observation of the world.

Indeed, Cassiano dal Pozzo holds an important place in the histories of both art and science. He was a member of the Accademia dei Lincei, founded in 1603 by Federico Cesi. This was the first scientific academy in Europe, and was based on the principle of direct observation; it was named after the wild lynx, known for its sharp eyesight. (Another member was the astronomer Galileo Galilei, known for challenging the Catholic church’s heliocentric view of the universe through his telescopic observations.) The display at the Barber includes a drawing of a dignified, softly rendered great white pelican by Vincenzo Leonardi, accompanied by a diagram showing how its syrinx compares to a human larynx, birdsong being one of the topics that fascinated the Lincei.

Samnite triple-disc breastplate (c. 1635), attrib. to Nicolas Poussin. Royal Collection Trust; © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, 2019

To form his paper museum, Cassiano employed a number of artists to copy antiquities, live and preserved specimens, as well as images from other collections. Nicolas Poussin spent most of his life in Rome attached to the dal Pozzos’ circle, despite invitations to work for Louis XIV. Only a few of Cassiano’s drawings are attributed to Poussin, but among them are front and back views of the Samnite warrior armour, on display at the Barber. Poussin also used drawings from the paper museum as inspiration for his paintings, and Cassiano commissioned the artist’s first series of paintings of the Seven Sacraments.

After Cassiano’s death, Carlo Antonio continued to develop the collection, but on his death it passed into papal hands before being split up and sold, largely to George III. Most of the drawings therefore still remain in the Royal Library at Windsor, with others in the British Library, British Museum, Sir John Soane’s Museum, the Institut de France, and elsewhere. ‘The Paper Museum: The Curious Eye of Cassiano dal Pozzo’, which has been curated by MA students from the University of Birmingham, is the second exhibition in the partnership between the Royal Collection Trust and the Barber.

Mosaic emblema: marsh scene with birds (c. 1627), unidentified Italian artist. Royal Collection Trust; © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, 2019

The curators have taken the opportunity to draw on the broader collections of the university, bringing geological specimens and books together with Cassiano’s drawings. The books show how the drawings informed his scholarship, including the L’Uccelliera (The Aviary) that he presented to Cesi after his election to the Lincei and which featured engraved versions of some of his drawings to prove parts of the argument. The paper museum also informed the contemporary and continuing scholarship of others, demonstrated by a plate from Bernard de Montfaucon’s 15-volume encyclopaedia of the ancient world (published in 1724), which used images of Roman mosaics from among Cassiano’s drawings.

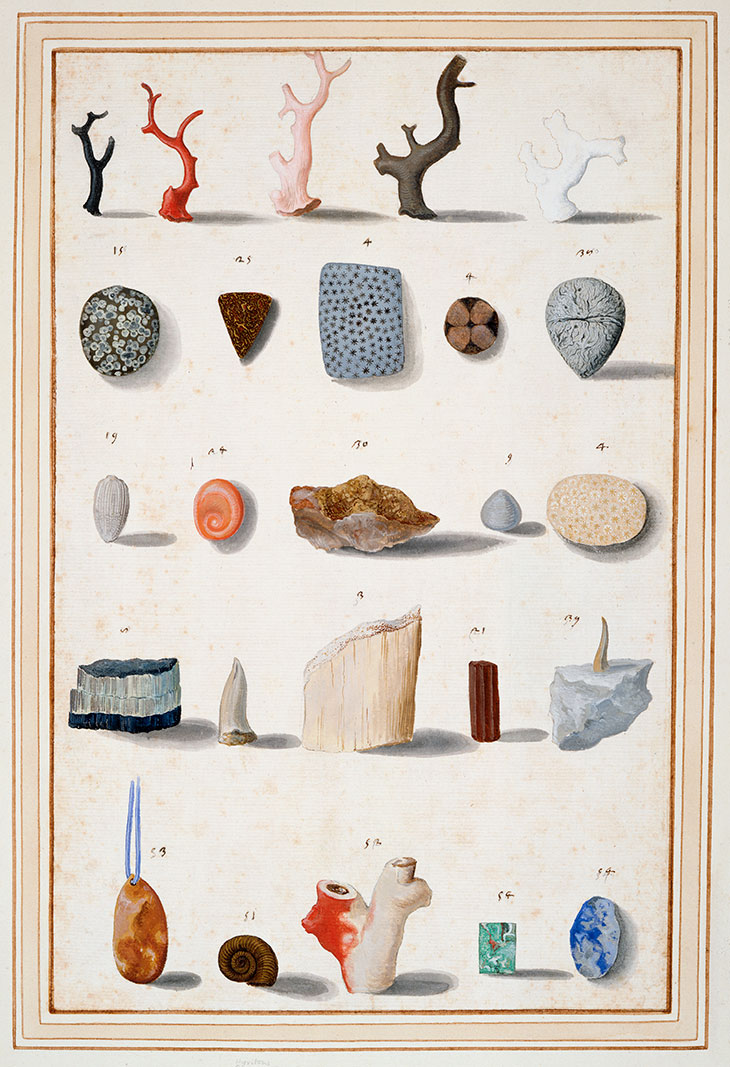

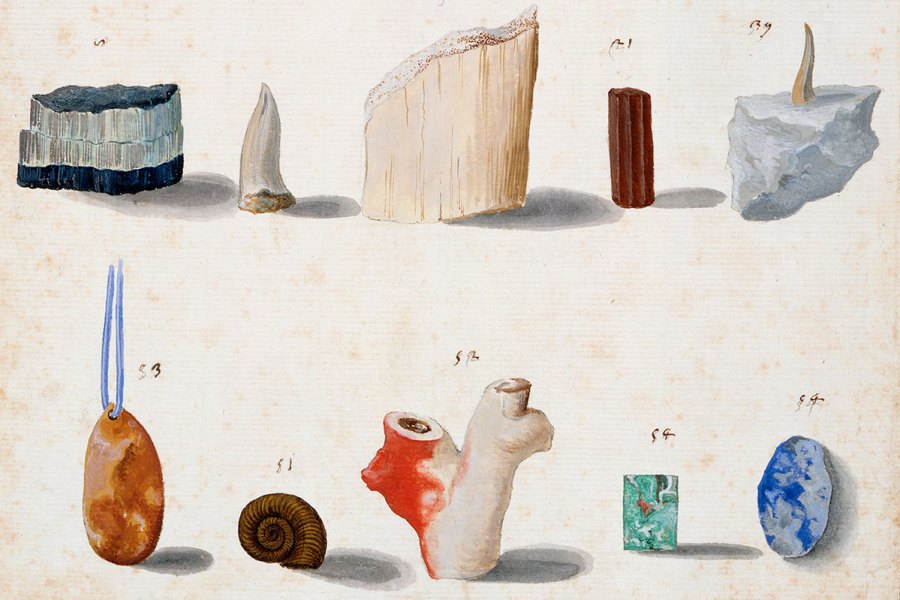

From the Lapworth Museum of Geology, meanwhile, come a series of geological specimens similar to those shown in a watercolour by Vincenzo Leonardi. Displayed alongside the drawing, the beautifully subtle colours and textures of the specimens become all the more compelling. Prominent among them is a piece of fossilised mammoth tusk, similar to one sent to Cesi. The Lincei were instrumental in showing that these objects, previously thought to be fragments of giants’ bones, were in fact elephant fossils.

Lapidary and ‘figured’ stones, corals, fossils, semi-precious stones and minerals (c. 1630–40), Vincenzo Leonardi. Photo: Royal Collection Trust; © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, 2019

Thus, the paper museum reperforms its original function. Brought together with original specimens, and literary texts, the drawings work to disseminate knowledge about antiquity and the natural world. The curators compare the dal Pozzos to Instagrammers and ask visitors to contribute drawings of what they would put in a paper museum today, with many responding with concerns over climate change.

Since 1996, the Royal Collection Trust have been working with Harvey Miller Publishers and the Warburg Institute to publish a complete illustrated catalogue raisonné of the paper museum. Thirty-two of the 37 volumes have now been published, with the remainder due next year. It is to be hoped that the dal Pozzos’ vision will then become fully realised, presenting 21st-century viewers with a compelling argument for the importance of visually understanding our environment and our past.

‘The Paper Museum: The Curious Eye of Cassiano dal Pozzo’ is at the Barber Institute of Fine Arts, Birmingham, until 1 September.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home