The Lebanese sculptor Alfred Basbous (1924–2006) visited Henry Moore’s studio in 1972, a year when public sculptures were unveiled all over Britain. By that point in his career, Basbous had established himself in Beirut, studied in Paris at the École des Beaux-Arts, and exhibited at the Rodin Museum, but he had never seen a government be so supportive of art and artists as in Britain. He prevailed upon his own government to emulate this. Beirut in the 1970s was among the most progressively liberal cities of the Middle East, with an established art scene of which Basbous and his brothers were part, but much of Lebanon was still ambivalent about the visual – and particularly figurative – arts. So Basbous decided to take the initiative and, with the help of his siblings, turn his hometown of Rachana into an open-air sculpture park. It is now a UNESCO site, and he is one of Lebanon’s most celebrated modern artists.

Constantin Brâncuși’s spirit hangs over the current exhibition of Basbous’s work at Sophia Contemporary Gallery in London. It is particularly evident in the elongated, abstract bronzes Femme Flamme (1985) and Woman Figure (1992) at the gallery’s entrance: they owe a lot to the modernist master’s 1923 sculpture Bird in Space, in which the ascent of the bird rather the bird itself is captured. Like Brancusi – and indeed Moore – Basbous was interested in creating artefacts that seem both modern and ancient at the same time. Seeing his works in this pristine gallery is a disconcerting experience, akin to visiting an art fair packed with mute but powerful prehistoric and classical objects whose intensity is heightened – and made strange – by the modern white space around them.

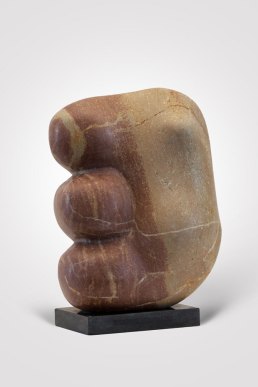

Some pieces, such as Phoenician Head (2003), explicitly draw on Lebanon’s ancient roots, while Torse (1970), Femme Acroupie and Femme Allongée (both 1972) and the ovoid marble Woman Nude (2001) have a hefty, Willendorf Venus quality about them. Both Basbous’s son and the exhibition curator note that, in Basbous’s lifetime, Lebanon lacked a strong sculptural tradition beyond antiquity. It is almost as if the artist were labouring not simply to bring modernist sculpture to the country, but to revive and invent a longer history in which to embed it.

Of all the works on display here, you don’t get much more primal and vital in spirit than Taureau (2003). Hard edges trace the rounded bronze body of a bull, from its bold, square head to a softly concealed tail. This discreet softness is something of a hidden artist’s signature in the works. It’s easy to miss the thin, gentle spines shaping the backs of his female forms, but when you do spot them it adds to a sense of true pathos. Among the dark bronzes and pale marbles, Woman (1982) made out of gleaming polished bronze, draws the eye – as does a gold tooth at the corner of a sculpted smile. All the sculptures have a tactile quality, too, and it is worth touching them to better appreciate their forms.

Basbous’s public statues are truly monumental: it’s difficult to tell whether much force is lost in these smaller indoor pieces, but many of them – such as a gypsum maquette for Family, the final version of which stands five metres tall in Bikfaya – seem to pull something of the outside world into their own forms. Basbous’s use of the openings in his bronzes, which is apparent throughout his career, culminates in 2004’s Profile, which is the first thing you see as you arrive in the gallery. Punning on its title, the statue’s thin, totemic face is visible when you look at it straight on, but its true personality is revealed only in profile: as you move around it a harp-shaped void, which accounts for most of the sculpture’s size and replaces its cheeks and eyes, becomes apparent.

Syrene (1985), an elegantly cubism-inflected female figure, contorted around a similar aperture and seemingly caught between two forms – human and avian – looks as if it could have been made at the same time. Basbous would often revisit and remake certain works decades later, in different materials and sizes. It seems as though, rather than evolving in phases throughout his career, his motifs have existed forever: or at least, the show is cleverly framed to emphasise his importance as a fully-formed talent for the majority of his career.

For years now, young sculptors in Lebanon have been inspired by Basbous’s pioneering example. He looked to Western modernists for inspiration: now, at a time when the citizens of select Middle Eastern countries are being banned from entering the US, it seems more important than ever that we also expand our artistic horizons. The art at Sophia Contemporary is part of a sculptural tradition that has long been engaged with the idea of civilisation and how art can reflect it: how art is, in fact, the marker of civilisation. And if a civilisation does not accord art its true value, Basbous seems to say, it is the artist’s job to make it part of the landscape.

‘Alfred Basbous, Modernist Pioneer’ is at Sophia Contemporary Gallery, London, until 22 April.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home