When ISIS fighters detonated explosives inside the gate of the Temple of Nabu at Nimrud earlier this month, they destroyed more than a reconstructed ancient temple. They attacked one of the Assyrian empire’s greatest centres of learning.

A screenshot from the ISIS video showing the Temple of Nabu prior to being destroyed

The temple was originally constructed by the Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II (ruled from 883–859 BC) to stand alongside the new palace he had built for himself on top of the citadel at Nimrud (this palace was also destroyed by ISIS last year). The patron god of writing and scribes, Nabu was originally worshipped in the southern Mesopotamian city of Borsippa where he was venerated as the son of the chief Babylonian god Marduk. Ashurnasirpal acknowledged the cultural debt by naming the new temple Ezida, meaning ‘the true house’, the same name given to the temple of Nabu in Borsippa.

An ISIS video showed footage of the Fish Gate at the Temple of Nabu in Nimrud, along with the ‘mermen’ statues representing the Seven Sages that flanked the entrance

Little remains of Ashurnasirpal’s temple, for the later king Adad-Nirari III (ruled 811–783 BC) carried out a massive project to rebuild the temple in 798 BC. The new temple featured two equal-sized sanctuaries for Nabu and his divine consort Tashmetum. The main entrance, known as the Fish Gate, was flanked by two gold-plated statues of mermen who represented the mythical Seven Sages who had brought knowledge to the earth in primeval times.

Statues flanking the Fish Gate were apparently destroyed in the explosion.

Inside the gates the temple of Nabu functioned as a centre of learning and scholarship, as evidenced by a library, which British excavators uncovered there in the 1950s. The names appended to documents in the archives reveal that families of scholars worked at the temple for generations, passing their profession from father to son.

What forms did their scholarship take? Out of around 300 tablets found in the library 30 per cent concerned the interpretation of omens. Lunar and solar eclipses as well as astronomical observations of the stars, moon, and Venus were all thought to contain messages from the gods. Other texts explain the meanings of deformed births, or the patterns made by crawling ants or flocks of birds. Still others contained illustrated instructions for how to read the livers of slaughtered animals. Scholars from the temple routinely wrote to the royal court to keep the king informed of the latest omens.

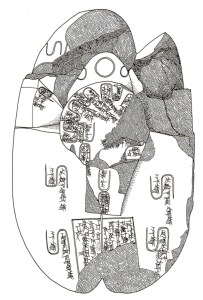

An illustration showing a model of a liver used for interpreting omens. Plate 36 from Literary Texts from the Temple of Nabu, by D.J. Wiseman and J.A. Black

Another 30 per cent were incantation texts, usually related to medical issues. It was hoped that ritual repetition of the formulas could cure various conditions such as epilepsy, toothaches, and baldness. Possibly more useful was a catalogue of medicinal plants also found in the library. The rest of the tablets include a list of proverbs, prayers to various gods, and inscriptions prepared by the scribes to record the official histories of the Assyrian kings.

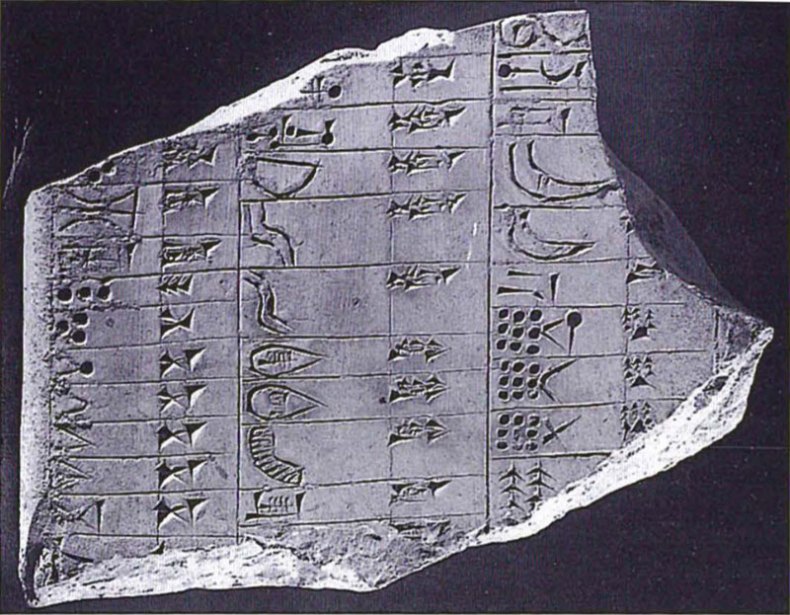

Possibly the most fascinating documents from the temple archive are several tablets featuring charts which show cuneiform signs from the scribe’s own time alongside attempts to reconstruct the earliest cuneiform signs used two thousand years earlier. The signs do not closely resemble what we know of the earliest cuneiform, but it was an admirable effort and one that showed a serious attempt by the scribes to understand their own past.

One of the tablets from the Temple of Nabu in Nimrud, which features Neo-Assyrian cuneiform side by side with attempts at reconstructing older cuneiform signs. P. 208 of Nimrud: An Assyrian Imperial City Revealed, by Joan Oates

Day-to-day life in the temple often featured mundane tasks and petty bureaucratic disputes. One letter speaks of the growth of fungus in the inner courtyard and in some of the storehouses and attempts by the priests to remove it. Another letter to the king complained that a priest named Pulu was making unauthorised changes to the temple furnishings and modifying some of the rituals. ‘No one can do [anything]; there is an order to remain silent’, wrote the traditionally-minded complainant, adding ‘But they have changed the old rites!’ Another letter, possibly from the same author, found fault with an upcoming ceremony involving a visit to the temple by a statue of the goddess Ishtar because ‘it is not ancient – your father introduced it.’

The tablets from the Nabu Temple archive are now housed in the British Museum in London and the Iraq Museum in Baghdad. The mermen which once guarded the entrance to the temple were still standing there, albeit broken and missing their gold plating, when ISIS blew up the Fish Gate. Video footage shows broken pieces of the statues lying amongst the rubble. The symbolic significance of destroying the entrance to what was once a centre of ancient learning is obvious.

For more information on the Temple of Nabu, try these publications:

Jeremy Black, ‘The Libraries of Kalhu’, pp. 261–266 in New Light on Nimrud: Proceedings of the Nimrud Conference, 11th–13th March 2002 (London: British School of Archaeology in Iraq, 2008).

Steven W. Cole and Peter Machinist, Letters from Priests to the Kings Esarhaddon and Assurbanipal [State Archives of Assyria Vol. 13] (Helsinki: Helsinki University Press, 1998).

Joan Oates and David Oates, Nimrud: An Assyrian Imperial City Revealed (London: British School of Archaeology in Iraq, 2001).

Eleanor Robson, ‘Ezida, the god Nabu’s temple of scholarship’, Nimrud: Materialities of Assyrian Knowledge Production, The Nimrud Project at Oracc.org, 2015.

D.J. Wiseman and J.A. Black, Literary Texts from the Temple of Nabu [Cuneiform Texts from Nimrud, Vol. 4] (London: British School of Archaeology in Iraq, 1996).

The centre of learning destroyed by ISIS in Iraq

Screenshot from ISIS video showing the destroyed 'mermen' statues of the seven sages at the Fish Gate, Temple of Nabu, Nimrud, Iraq

Share

When ISIS fighters detonated explosives inside the gate of the Temple of Nabu at Nimrud earlier this month, they destroyed more than a reconstructed ancient temple. They attacked one of the Assyrian empire’s greatest centres of learning.

A screenshot from the ISIS video showing the Temple of Nabu prior to being destroyed

The temple was originally constructed by the Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II (ruled from 883–859 BC) to stand alongside the new palace he had built for himself on top of the citadel at Nimrud (this palace was also destroyed by ISIS last year). The patron god of writing and scribes, Nabu was originally worshipped in the southern Mesopotamian city of Borsippa where he was venerated as the son of the chief Babylonian god Marduk. Ashurnasirpal acknowledged the cultural debt by naming the new temple Ezida, meaning ‘the true house’, the same name given to the temple of Nabu in Borsippa.

An ISIS video showed footage of the Fish Gate at the Temple of Nabu in Nimrud, along with the ‘mermen’ statues representing the Seven Sages that flanked the entrance

Little remains of Ashurnasirpal’s temple, for the later king Adad-Nirari III (ruled 811–783 BC) carried out a massive project to rebuild the temple in 798 BC. The new temple featured two equal-sized sanctuaries for Nabu and his divine consort Tashmetum. The main entrance, known as the Fish Gate, was flanked by two gold-plated statues of mermen who represented the mythical Seven Sages who had brought knowledge to the earth in primeval times.

Statues flanking the Fish Gate were apparently destroyed in the explosion.

Inside the gates the temple of Nabu functioned as a centre of learning and scholarship, as evidenced by a library, which British excavators uncovered there in the 1950s. The names appended to documents in the archives reveal that families of scholars worked at the temple for generations, passing their profession from father to son.

What forms did their scholarship take? Out of around 300 tablets found in the library 30 per cent concerned the interpretation of omens. Lunar and solar eclipses as well as astronomical observations of the stars, moon, and Venus were all thought to contain messages from the gods. Other texts explain the meanings of deformed births, or the patterns made by crawling ants or flocks of birds. Still others contained illustrated instructions for how to read the livers of slaughtered animals. Scholars from the temple routinely wrote to the royal court to keep the king informed of the latest omens.

An illustration showing a model of a liver used for interpreting omens. Plate 36 from Literary Texts from the Temple of Nabu, by D.J. Wiseman and J.A. Black

Another 30 per cent were incantation texts, usually related to medical issues. It was hoped that ritual repetition of the formulas could cure various conditions such as epilepsy, toothaches, and baldness. Possibly more useful was a catalogue of medicinal plants also found in the library. The rest of the tablets include a list of proverbs, prayers to various gods, and inscriptions prepared by the scribes to record the official histories of the Assyrian kings.

Possibly the most fascinating documents from the temple archive are several tablets featuring charts which show cuneiform signs from the scribe’s own time alongside attempts to reconstruct the earliest cuneiform signs used two thousand years earlier. The signs do not closely resemble what we know of the earliest cuneiform, but it was an admirable effort and one that showed a serious attempt by the scribes to understand their own past.

One of the tablets from the Temple of Nabu in Nimrud, which features Neo-Assyrian cuneiform side by side with attempts at reconstructing older cuneiform signs. P. 208 of Nimrud: An Assyrian Imperial City Revealed, by Joan Oates

Day-to-day life in the temple often featured mundane tasks and petty bureaucratic disputes. One letter speaks of the growth of fungus in the inner courtyard and in some of the storehouses and attempts by the priests to remove it. Another letter to the king complained that a priest named Pulu was making unauthorised changes to the temple furnishings and modifying some of the rituals. ‘No one can do [anything]; there is an order to remain silent’, wrote the traditionally-minded complainant, adding ‘But they have changed the old rites!’ Another letter, possibly from the same author, found fault with an upcoming ceremony involving a visit to the temple by a statue of the goddess Ishtar because ‘it is not ancient – your father introduced it.’

The tablets from the Nabu Temple archive are now housed in the British Museum in London and the Iraq Museum in Baghdad. The mermen which once guarded the entrance to the temple were still standing there, albeit broken and missing their gold plating, when ISIS blew up the Fish Gate. Video footage shows broken pieces of the statues lying amongst the rubble. The symbolic significance of destroying the entrance to what was once a centre of ancient learning is obvious.

For more information on the Temple of Nabu, try these publications:

Jeremy Black, ‘The Libraries of Kalhu’, pp. 261–266 in New Light on Nimrud: Proceedings of the Nimrud Conference, 11th–13th March 2002 (London: British School of Archaeology in Iraq, 2008).

Steven W. Cole and Peter Machinist, Letters from Priests to the Kings Esarhaddon and Assurbanipal [State Archives of Assyria Vol. 13] (Helsinki: Helsinki University Press, 1998).

Joan Oates and David Oates, Nimrud: An Assyrian Imperial City Revealed (London: British School of Archaeology in Iraq, 2001).

Eleanor Robson, ‘Ezida, the god Nabu’s temple of scholarship’, Nimrud: Materialities of Assyrian Knowledge Production, The Nimrud Project at Oracc.org, 2015.

D.J. Wiseman and J.A. Black, Literary Texts from the Temple of Nabu [Cuneiform Texts from Nimrud, Vol. 4] (London: British School of Archaeology in Iraq, 1996).

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

Share

Recommended for you

Palmyra’s legacy is everywhere – and ISIS could never have erased it

The city’s ancient ruins inspired buildings around the world, many of which are now heritage sites themselves

ISIS destroys Iraq’s oldest Christian monastery

Art News Daily : 20 January

A tribute to Khaled al-Asaad, the archaeologist killed by Isis in Palmyra

The octogenarian dared to stand up to militants at the ancient site