This feature was published in the November 2020 issue of Apollo. Preview the current issue and subscribe here.

There is little to announce the Musée Cernuschi when you are walking along the Avenue Vélasquez, leading into the parc Monceau in the 8th arrondissement of Paris. This neoclassical hôtel particulier, which holds one of the most important collections of Asian art in Paris, sits alongside other mansions on the row, partly hidden by trees and with just a discreet sign bearing its name. The cool white stone facade is untypical in the heart of Haussmann’s Paris, better known for its warm, creamy sandstone. Columns frame the entrance, which is headed by a balcony where mosaic medallions of Aristotle and Leonardo da Vinci are set to either side. The words ‘Février’ and ‘Septembre’ are engraved in the stonework, in homage to those two months of revolution in France, in 1848 and 1870, that led to the creation of the Second and Third Republics.

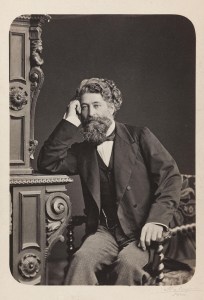

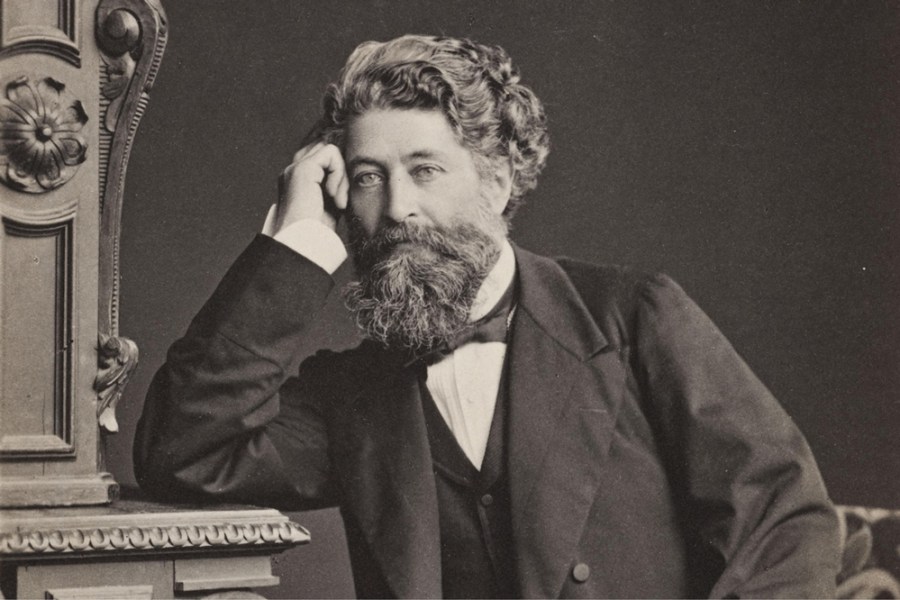

Henri Cernuschi photographed in 1876 by Count Stanislaw Julian Ostrorog (‘Walery’). Musée Cernuschi, Paris

The philosopher and artist, and the great victories of republicanism, were all inspirations to Enrico (later Henri) Cernuschi. Born into a wealthy Milanese family in 1821, for the two last decades of his life he lived alone in this mansion, surrounded by the objects he had acquired from his travels in Asia. In 1893, he opened his home to the public, allowing visitors a first glimpse of his trove of objects. He bequeathed his collection to the city of Paris in 1896 when he died, and two years later the mansion became a museum. In June 2020 it reopened, or rather reopened again, because it had welcomed its first visitors in March, after months of renovations, but was forced to shut again two weeks later by the Covid-19 lockdown. The renovations came after years of planning to present a new display of its permanent collection, the first change since 2005. There are fresh colours on the walls, modernised and additional glass casing, special lighting, a new room dedicated to painting, and an added raised platform in the main room for the huge bronze Buddha in the collection. Some 600 objects are now on show, up from nearly 500 out of a total of almost 15,000.

An emphasis on how the collection was formed has guided the new displays, explains the museum’s director, Eric Lefebvre, when I visit at the end of September. Greater prominence is given to Henri Cernuschi, who now has a corner dedicated to him in the lobby. A large photograph of the bearded founder hangs at the foot of the wide staircase leading to the main rooms, and underneath it a large flat screen shows images and a map of his world travels tracing the path he followed, notably through Asia. We also learn of his colourful early life. A passionate republican, Cernuschi played a key role in the Risorgimento of 1848 that resulted in the liberation of Milan from Austrian occupation. After the short-lived Roman Republic and a stint in prison, he fled to Paris in 1850, where his republicanism also riled Napoleon III. He was forced into exile briefly, but then returned to build a strong reputation as a financier, co-founding the Banque de Paris in 1869, whence today’s BNP Paribas, and developing an influential monetary theory. A year after the founding of France’s Third Republic in 1870 he was naturalised and took the name Henri. But the violence of the period, and notably the death of a close friend who was gunned down at the height of the Paris Commune, encouraged him to take a round-the-world voyage. In July 1871 he set out from Liverpool for New York with his travel companion Théodore Duret, an art critic and fellow republican. They set sail from Bombay back to France in December 1872.

Vase in the form of a heavenly rooster (18th century), Qing dynasty, China, gilt bronze, ht 26cm. Musée Cernuschi, Paris Photo: Stéphane Piera; © Paris Musées/Musée Cernuschi

The only known account of their tour comes from Duret’s Voyage en Asie, published in 1874. While the trip fuelled Cernuschi’s passion for Asia and collecting, he was already familiar with the art world in Paris. Traces of the financier are also evident in how he acquired his objects – applying himself to art collecting as he did to banking – with precision and good book-keeping. All the objects in his collection were obtained at auction or through private, documented transactions, keeping the Musée Cernuschi free of the sort of controversy now dogging institutions such as the Musée du Quai Branly, which also holds a significant collection of Asian art and faces a long list of restitution claims for certain objects, notably from Africa. The only contested item in the Cernuschi holdings is its great bronze Buddha, ‘acquired in slightly special circumstances’, Lefebvre tells me.

The museum’s grand staircase takes us directly to the permanent collection, which is contained in a few side rooms surrounding the large double-height front room. The latter was a radical feature when it was built, as Cernuschi broke with the usual proportions of the hôtel particulier to join two floors and create a space that corresponds more to a temple. Before you enter these rooms there are a few glass cases containing a selection of objects acquired by Cernuschi in his lifetime. The rest of the permanent exhibition consists of pieces acquired after his death, intermingled with items from the founding collection, so that ‘[Cernuschi] is present as a kind of watermark’, as Lefebvre puts it. The cases full of objects acquired only by Cernuschi himself hold a delightful hodgepodge of items, from exquisite bronze animals to incense burners and wine goblets. Tiny LED spotlights inside the cabinets now bring out details such as the delicate and differing fur strokes on the body of a bronze rabbit’s body, or the intricate mosaic patterns on the shells of bronze tortoises. One stand-out piece is a lacquered and gilded wood tiger from the Edo period in Japan that once belonged to Sarah Bernhardt. Its fiery eyes stare out at visitors, and its side-sweeping stance is such that it looks capable of pouncing at any moment. In a journal entry of 17 January 1885, Edmond de Goncourt describes a desperate Sarah Bernhardt offering to sell Cernuschi this prized possession for half the amount she had paid the art dealer Siegfried Bing.

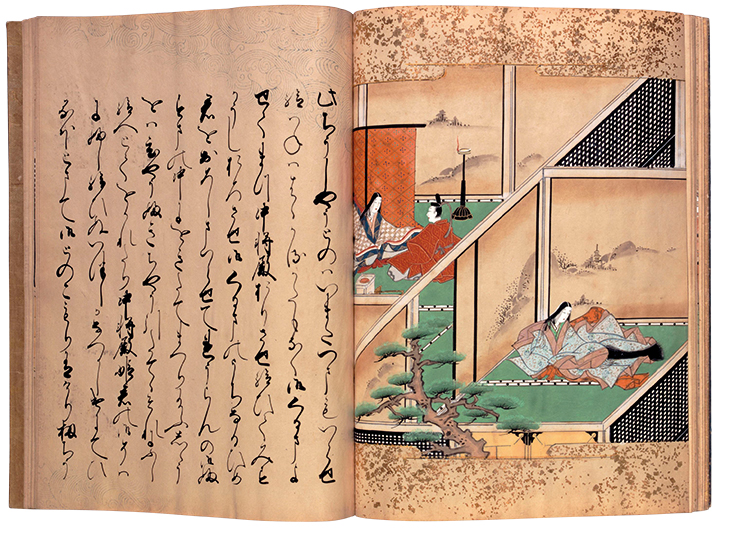

Shigure Monogatari (1600–50), Japan. Photo: © Paris Musées/Musée Cernuschi

Today the Musée Cernuschi is home to the second most important collection of Asian art in Paris. While the Musée Guimet, down the road in the 16th arrondissement is bigger, the two are better viewed not as rivals but as complementary. The Guimet collection covers a larger territory that includes Central Asia, Cambodia and India, while the Cernuschi’s concerns itself with China, Japan, Korea and Vietnam and, in its original form, concentrated exclusively on objects from China and Japan. Even today the collection is mostly made up of items from these two countries – some 8,000 from China, principally bronze and ceramic pieces but also important stone sculptures and paintings on silk acquired both by Cernuschi and by the museum subsequently; and around 3,600 bronze and ceramics and some manuscripts from Japan, most of which Cernuschi acquired during his voyage of 1871–72. His focus on bronze in particular was unusual at the time, Lefebvre tells me. ‘He very quickly had this intuition that the Europeans were interested in Asian ceramics due to their fascination with porcelain, and they also were interested in polished wood […] but what they had not understood was the interest in metal, in particular bronze.’ So, Cernuschi decided to concentrate on collecting bronzes – perhaps not surprising for a figure whose most important theory was ‘bimetallism’, which advocated a monetary system based on the values of gold and silver.

On their travels, Cernuschi and Duret also visited India, as well as Sri Lanka and the island of Java, but they acquired objects only from China and Japan. Pieces from Vietnam and Korea entered the museum’s collection in the 20th century through donations and acquisitions. In 1927, a businessman based in Hanoi sold around 100 objects to the museum: neolithic stone carvings, bronze weapons from the 1st millennium BC and 11th–17th century ceramics. This was the foundation of the museum’s Vietnamese collection, which now numbers some 1,800 items. From three digs in northern Vietnam in 1934–39 by the Swedish archaeologist Olov Janse came another 1,500 pieces. (His findings also went to the Guimet and a museum in Hanoi, as part of an agreement between the city of Paris and Vietnam’s ministry of education.)

The permanent collection is now presented more chronologically than it was before, and the specific geographical reach of the museum is underlined by a series of ‘Wide Angle’ cases that focus on a single country. The greater emphasis on the museum’s collection of works from outside China has been one of the major innovations of the new permanent-collection displays. And so, for example, in the first of the side rooms there is a ‘Wide Angle’ on Vietnam, with a selection of objects from the prehistoric Dong Son culture from the north of the country.

Another exceptional piece, ‘one of the great masterpieces of the museum, perhaps the greatest and certainly the most famous’, Lefebvre says, is the extraordinary Chinese bronze you vase, more commonly known as ‘the Tigress’, from around 1100–1050 BC (the late Shang era). The museum bought the piece in 1920, when European sinologists and archaeologists encouraged the institution to focus on ancient and prehistoric China, in light of the important digs and discoveries that had started in the 1910s. Now in its own glass case, the ‘Tigress’ is in the centre of the first side room. Under the new lighting, it is one of the winners in the revamp: its intricate engravings appear crisply to the naked eye and one can explore all its strange details. Believed to have been used as a container for alcohol, Lefebvre says it remains ‘very ambiguous and we can never work it out because it is a period when we have no real texts, only short ones and they do not allow us to explain the theme’. The vase appears to be a fusion of a ferocious tiger and a protective parent nestling a human baby in its grip. The animal and human forms are covered with other representations – the tiger has a goat-like figurine on its head and dragons on its shoulders, while the human has two birds on its shoulders. On the tiger’s back there is an elephant’s trunk that turns into the tiger’s tail. ‘What we have is a kind of perpetual transformation, with all forms of animals, imaginary and real, a kind of complete bestiary,’ Lefebvre says.

You ‘Tigresse’ vase (11th century BC), Shang dynasty, China. Photo: Stéphane Piera; © Paris Musées/Musée Cernuschi

Another signature item in the collection, though often overshadowed by the Tigress, is a Shang dynasty ding vase (1050–771 BC), acquired by Cernuschi. Like the ‘Tigress’, it has also been given prominence in the new presentation due to the sharp lighting directed at the inscription on the inside, which pays homage to the Emperor. With its 110 Chinese characters, this inscription inside the vase, set out in 11 columns of ten characters each, is the longest such inscription in any Chinese vase from the period held in Europe. For years, Lefebvre tells me, he welcomed the public, telling them all about the extraordinary inscription, ‘and visitors said: “But where is the inscription?”’ Nobody could see it – without special lighting and exhibited slightly higher than it is now, the inscription was invisible.

From the start, Cernuschi envisaged the 18th-century bronze Amida Buddha as the centrepiece of his collection and it remains as spectacular now as one imagines it must have been when Duret described it as ‘a unique find’. At 4.4m high, it now sits on a raised platform in the main room, facing the large windows that give on to the park. Cernuschi and Duret acquired the Buddha through local intermediaries in the art market, who noted the travellers’ interest in bronze, and negotiated with monks from a temple in a Tokyo neighbourhood that had burned down, but the Buddha, which had been outside the temple, remained intact. The two men bought the Buddha for 500 gold coins (ryo), but the purchase was not welcomed by everyone, Lefebvre explains. After the monks had sold the Buddha but before the statue was shipped out of Japan, the surrounding villagers got wind of the deal and went to Cernuschi and Duret to ask them to abandon their plan. But the two men ‘were intransigent, they said we bought the Buddha, we are taking it back!’ The monks were also keen to sell because their monastery already held other ancient statues and the clergy was facing hard times with new decrees from the Meiji Empire, which placed them in a state of bankruptcy.

It is hard for museums to exhibit Buddhas of this size in a way that does the great statues justice. One thinks of the nearly six-metre-high standing sixth-century Buddha from China that is squeezed into the well of the British Museum’s North Stairs. By contrast at the Cernuschi, the main room was literally made to measure for its huge resident. With a new staircase leading up to the raised platform, visitors can view the Buddha from all angles, and in a comparatively uncluttered environment from its original setting, as historic photographs show.

Photograph of the Hôtel Cernuschi, taken in 1880, showing the Amida Buddha from the Meguro district of Tokyo. Photo: Paris Musées/Musée Cernuschi

The display of the permanent collection concludes with objects acquired by the museum in the 20th and 21st centuries and includes works by modern abstract painters such as Lee Ungno from Korea and Zao Wou-Ki from China. In 2016 the museum received a donation of works by Zao Wou-Ki, which has strengthened its claim to be a key institution for both ancient and modern Chinese art. And in the 1980s, Ungno himself donated some 40 works, inaugurating the museum’s Korean collection, which now numbers around 200 objects. When Cernuschi was travelling around Asia, the Korean peninsula was not yet accessible to visitors, and there is only one known object from the country that he acquired – a bell – and this most likely at an auction in Japan.

Gandharva (late fifth century), Northern Wei dynasty, China. Photo: Stéphane Piera; © Paris Musées/Musée Cernuschi

For the display of silk scrolls, a new room that receives no natural light has been created. To ensure their preservation, the paintings hanging behind glass panels change every three months; this is the first time since 1980 that it has been possible for the public to see them. When you step into this hermetically sealed room, which allows in only one visitor at a time, the world falls silent, the air feels completely still, we are entirely alone in our contemplation. Cernuschi, one imagines, would have approved. From this place the pushchairs, joggers and dogs of the parc Monceau seem another world away.

From the November 2020 of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home