The setting for Goldsmiths Centre for Contemporary Art (CCA) on campus at Goldsmiths University in New Cross recalls the starting point for the Chicago Imagists, 14 artists who all studied at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) during the 1960s and ’70s, and the subject of the CCA’s current exhibition. The SAIC is closely linked to the Art Institute of Chicago, located across the road, and tutors regularly send their students to explore the museum’s collection.

‘Chicago Imagists’ is something of an umbrella term for the artists. After graduating many of them put on shows in Chicago under various group names including the Hairy Who, False Image and Nonplussed Some, each time with a different line-up. When their renown grew, as their shows spread to San Francisco and New York, the artists who made up these smaller groups were banded together. Their UK debut came in Sunderland in 1980 in an exhibition titled ‘Who Chicago?’. The current show title rearranges ‘who’ into ‘how’ in a similar wordplay to that often used by the Imagists – the ‘Hairy Who’ moniker was born when the artist Karl Wirsum arrived late to a conversation about the art critic Harry Bouras and asked ‘Harry who?’.

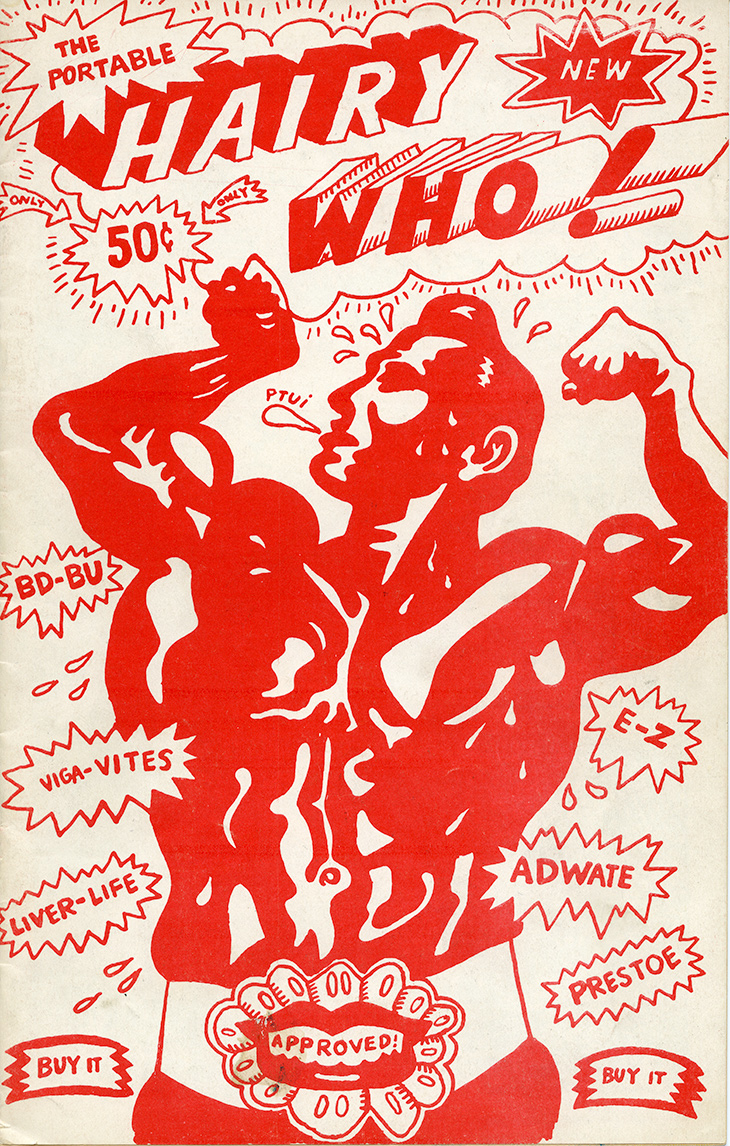

Front cover for ‘The Portable Hairy Who!’ (1966), Art Green. Courtesy Roger Brown Study Collection, The School of Art Institute of Chicago; © Art Green

The artists’ visual styles vary, but their outputs are linked by several themes, such as the rise of consumerism in the US in the decades after the Second World War. Art Green’s drawing for the front cover of ‘The Portable Hairy Who!’ (a catalogue for the eponymous exhibition of 1966) shows a clichéd image of a bodybuilder flexing his oiled biceps – an exaggerated version of masculinity as prevalent in advertising then as it is now. The bodybuilder is surrounded by fake supplement names such as ‘VIGA-VITES’, ‘LIVER-LIFE’ and ‘PRESTOE’. The visual language of the image is borrowed from the underground comix movement of the time, adding to the sense of parody.

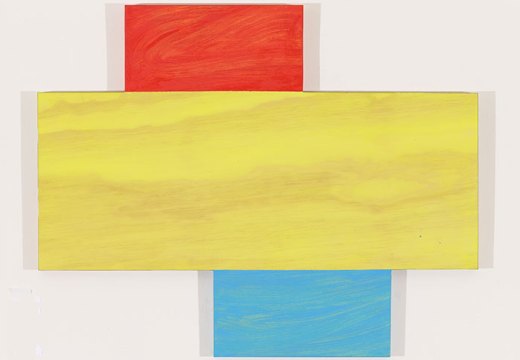

Double Hesitation (1977), Christina Ramberg. Courtesy Elmhurst College Art Collection; © the artist

There were a number of women associated with the Chicago Imagists, whose work frequently picks up the theme of gender roles and their social construction from a female perspective. Particularly notable are Christina Ramberg’s more subdued but still flatly graphic paintings. In Double Hesitation (1977) a woman’s body is fragmented and contorted into a grotesque shape by the bandages and delicately patterned tights that constrict it.

Many of the Imagists made regular visits to the Maxwell Street Market, a busy market in central Chicago. Ray Yoshida, who graduated from SIAC in 1953 before returning to tutor there in 1959 and later exhibiting alongside some of his students, called the toys, signs and general ephemera harvested on these trips ‘trash treasures’. Ed Flood and Jim Nutt, among others, took this idea and focused on pinball machine graphics and shop window signs as inspiration for their process. They wanted to create a similar graphic, machine-produced style of image. They achieved this by painting, often using bright colours, on the reverse of Plexiglass, so that when the work was hung on a wall no brush strokes or paint texture would show.

First Nighter (1968), Ed Flood. Courtesy Corbett vs. Dempsey and Cheryl L Cipriani; © the artist

Snooper Trooper (1967), Jim Nutt. Courtesy David Nolan Gallery, New York; © the artist

In Flood’s First Nighter (1968), layers of painted Plexiglass create the depth of a stage set on which a naked girl sings cheerfully, her hands crossed against her chest, an image mimicking the graphics found on some pinball machines as well as those of pulp books and films of the time. The words ‘Stage Struck’ are written in a pink cursive typeface and enclosed in a comic-book style bubble, just above ‘GIRLIE’ in gaudy lettering. Nutt’s Plexiglass paintings are more overtly grotesque. In Snooper Trooper (1967) a visor-capped authority figure peers at the viewer. The figure wears an earpiece, from which cartoonish lines zigzag, indicating he is being fed information – maybe giving him reason to be suspicious of the viewer. His skin is covered in brightly coloured boils and warts with a small prison shown at the top of his neck and a Hoover hose-like growth of a nose, which he presumably uses to sniff out wrong-doers. He is surrounded by smaller instruction manual-style images showing strange and slightly ominous scenes of what could be bizarre torture techniques. The painting is in a green wooden frame whose shape recalls that of a pinball-machine headboard. Pinball at the time was officially banned in Chicago, although the law doesn’t seem to have been too vigorously enforced; this painting appears to parody the more enthusiastic of enforcement officers.

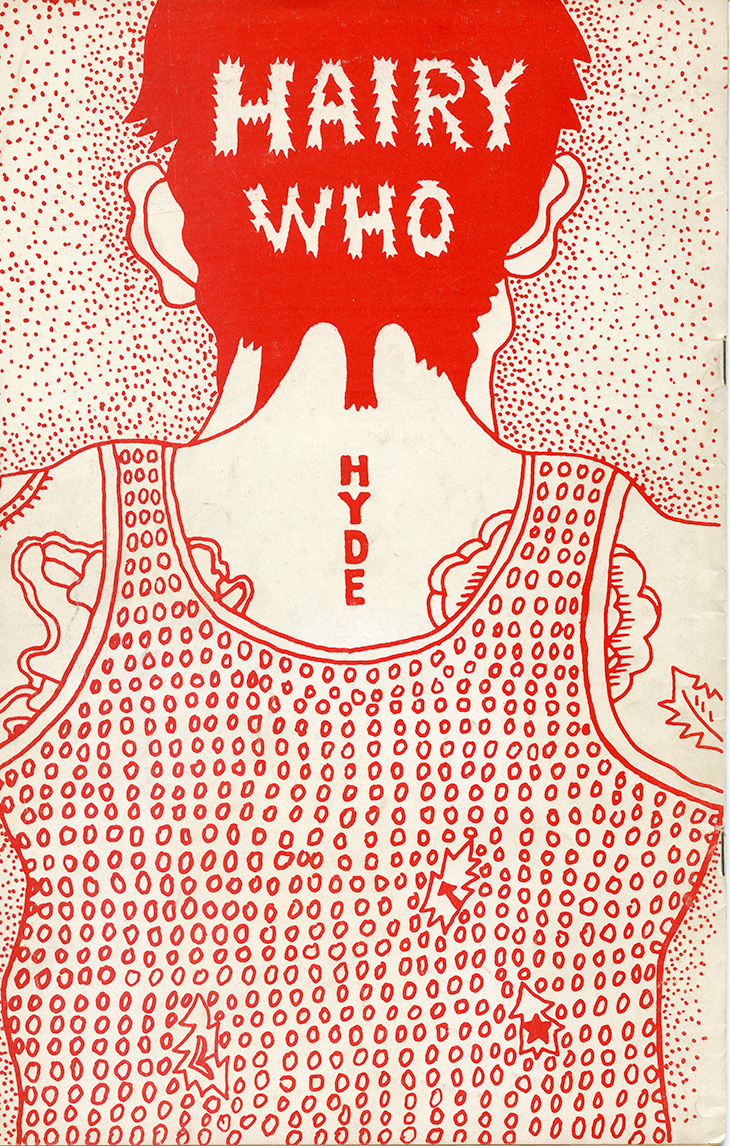

Back cover for ’The Portable Hairy Who!’ (1966), Karl Wirsum. Courtesy Roger Brown Study Collection, The School of Art Institute of Chicago; © the artist

In their various styles, all the Imagists explored what contemporary America was for them. The results are frequently garish and grotesque, and rarely subtle. This visual enthusiasm made things that might otherwise be dark or threatening seem silly, a subject for comedy, and quite possibly conquerable – an attitude with which all students should enter the wider world.

‘How Chicago! Imagists 1960s and ’70s’ is at Goldsmiths Centre for Contemporary Art, London, until 27 May.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home