From the May 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Nestled in the wealthy 16th arrondissement of Paris, a small park marks the life of one of the 20th century’s best-known Egyptologists. The Jardin Christiane Desroches-Noblecourt – not so far from where its namesake grew up – commemorates a woman whose life was formidable in endeavour and length: born in 1913, she died in 2011, having in 2008 received the Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour, France’s highest order of merit.

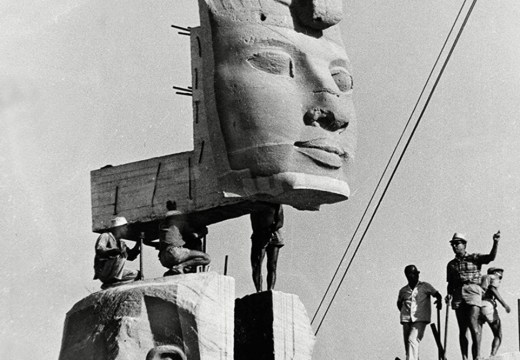

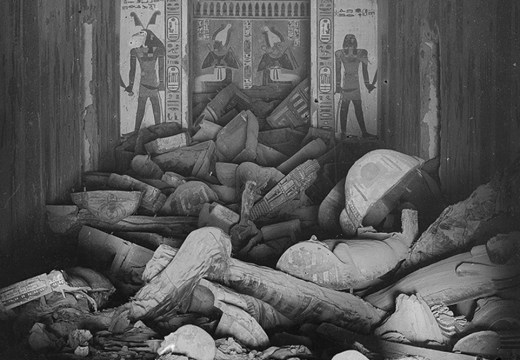

Desroches-Noblecourt’s legend has long been secure: her life spanned curatorial duties at the Louvre, membership of the French Resistance, and a high-profile role in UNESCO’s International Campaign to Save the Monuments of Nubia. This last ensured, between 1960 and 1980, the ‘salvage’ of innumerable structures and archaeological sites in Egypt and Sudan from flooding caused by the construction of the Aswan High Dam, and also gave impetus to the World Heritage Convention of 1972. Lynne Olson’s biography, drawing mostly on published sources, including Desroches-Noblecourt’s own memoir, narrates this life fluently. But it does little to question the conditions that gave rise to that legend and which still influence how we understand the preservation of heritage.

What’s missing is any account of the people who helped to make Desroches-Noblecourt’s life so singular, except when they are seen through her eyes: particularly the Egyptians and the Nubians without whom her career would not have existed. As a woman in the tiny, male-dominated – and often extremely malicious – field of Egyptology, Desroches-Noblecourt possessed exceptional clout, and achieved extraordinary things (even as she professed herself not to be a feminist).

Born into a privileged, left-leaning family, Desroches-Noblecourt’s parents gave her the freedom to pursue her career of choice. After she had attended the Lycée Molière, her father arranged for Christiane to discuss educational possibilities with Henri Verne, director of France’s national museums and head of the École du Louvre, where she took classes in Egyptology. In 1934, she went to work in the Louvre’s department of Egyptian antiquities, a position that for many years went unpaid; she became acting head of the department in 1940, finally getting a salary in 1942.

She did all this while deflecting the machinations of male colleagues and becoming involved with the wartime resistance network connected to the Musée de l’Homme in Paris. She first travelled to Egypt in 1937, sitting with the Aga Khan and Haile Selassie at the captain’s table on the SS Champollion (named, appropriately enough, for the decipherer of the Rosetta Stone). She conducted fieldwork in Egypt until 1992. At times, her male colleagues attempted to put her in her place: as the first woman fellow of the Institut français d’archéologie orientale in Cairo, she was told on her first dig to direct the camp’s cook and become its nurse (a role that she continued throughout her career). She quickly moved beyond such belittlement, however.

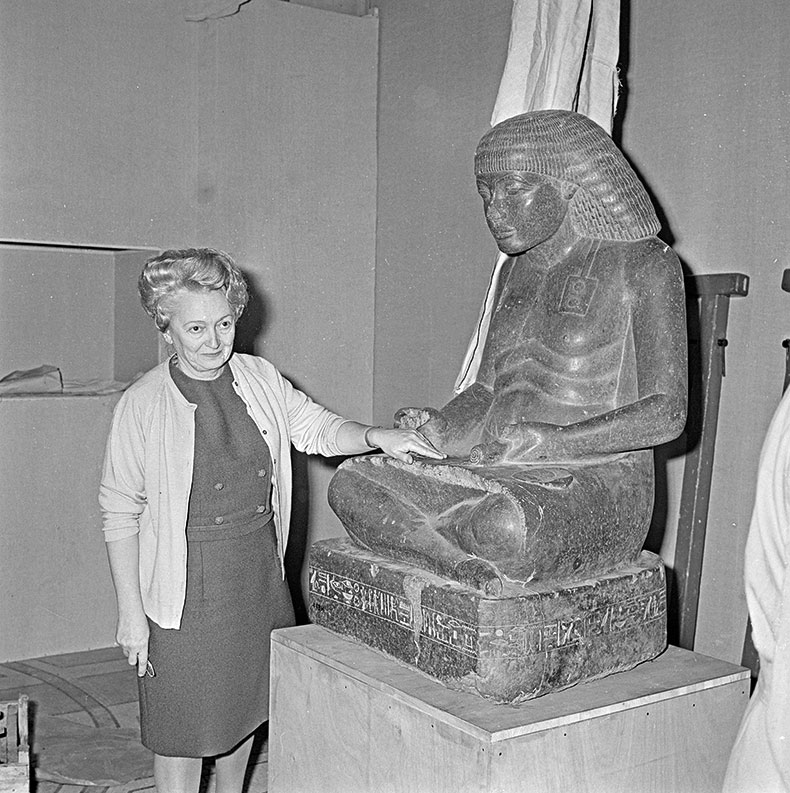

Christiane Desroches-Noblecourt at the ‘Tutankhamun and his Time’ exhibition at the Petit Palais in Paris in February 1967. Photo: Claude Lechevalier/Fonds France Soir/BHVP/Roger-Viollet

It was during the campaign in Egyptian Nubia in the 1960s and ’70s that Desroches-Noblecourt really came into her own, becoming instrumental in efforts to save, among others, the temples at Abu Simbel and Philae (she was barely involved in efforts on the Sudanese side of the Nubian border). But the book’s attempts to present Desroches-Noblecourt as singularly heroic and a ‘willful real-life version of Indian Jones’ are inappropriate. A vast project such the Nubian campaign can’t be attributed to any one individual, or even a select few. Beyond Desroches-Noblecourt, Olson singles out UNESCO director-general Réne Maheu and the French and Egyptian ministers of culture, André Malraux and Tharwat Okasha. She also discusses Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis’s close involvement in the Nubian campaign: documentation from the Kennedy Presidential Library makes it clear that Jackie’s efforts persuaded not only her husband to commit funding to the project, but also US government officials to persist in that effort after his death.

However, the flight of many thousands of Nubians in the face of the High Dam is mentioned only after 252 pages. It was a ‘sad fact of life that Egyptian authorities, as well as UNESCO officials, seemed far more worried about the fate of Abu Simbel’; but Olson’s account of the structures and archaeological sites follows the same patter. Desroches-Noblecourt certainly felt for the Nubians. Throughout the book, however, we are faced with descriptions of seemingly isolated – and certainly not populated – places inherently suitable to becoming monumental heritage: a ‘sad fact of life’ created through the repetition of such inaccurate representations by Egyptologists such as Christiane Desroches-Noblecourt. Such visions, too, still regularly drive preservation and ‘site management’: things first, not the people who live with them.

The book is not devoid of historical context: Olson documents how Desroches-Noblecourt’s work in Egypt was made possible first by colonialism, then by her skilful navigation of the politics of formal decolonisation and the Cold War. As often is the case with archaeological biography, however, too often the agency at stake is that of the protagonist. Throughout the book, Olson emphasises Desroches-Noblecourt’s thoughts about the Egyptians whom she got to know, particularly the workers on her archaeological sites with whom, we are told, she took care to develop close relationships. The account remains one-sided, though: what the Egyptians thought of Desroches-Noblecourt is reported through the remarks of her friends. To one interviewer, meanwhile, Desroches-Noblecourt stated that Egypt’s rural populace ‘have not changed in thousands of years’. This representation – of an unchanging and simple Egyptian peasant – has been debunked so many times that it is jarring to see it repeated uncritically here. Maybe, though, that’s how someone gets to be an empress.

Empress of the Nile: the daredevil archaelogist who saved Egypt’s temples ancient temples from destruction by Lynne Olson is published by Scribe.

From the May 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home