This piece is from the December 2018 issue of Apollo. Since its publication in print, Charlotte Prodger has been announced as the winner of this year’s Turner Prize.

How do you make something visible when it is already obvious? We are living in a time when man-made disasters, from the effects of climate change to the violation of refugee and migrant rights, to governments abusing populations under their control with impunity, are more heavily mediated than at any point in history, but when the possibility of change seems blocked. This, in turn, can lead to the idea that the problem is one of public apathy, or disconnectedness. If only people were more aware of the scale of the disaster; if only they cared more or had some deeper engagement with the subject, would they respond differently?

These sorts of questions appear to preoccupy some of the UK’s major art institutions right now, with a number of them commissioning – or collecting together – work with overtly ‘political’ themes. To do so raises questions: is art that attaches itself to current events in such a way any more or less political than that which apparently sticks to more abstract or intimate concerns? What kind of relationship is set up between the work, the subject matter and the audience? Does the work contain a call to action that goes beyond the usual conventions of privately traded or publicly funded art – and if so, on whose shoulders does that responsibility fall?

One impulse might be to produce work that tries to make people look again at a familiar subject, or to provoke conflicted or confrontational responses. This has been done several times around the subject of migration and borders, from Richard Mosse’s use of military surveillance technology to make images of people trapped at Europe’s periphery, to Marc Quinn’s forthcoming Odyssey, a sculpture made from blood donated by refugees and others. Often, there seems to be an implied challenge to the spectator: you don’t want to look but I am going to make you face up to this.

But what, then, is the artist doing as intermediary between the viewer and the pur-portedly unseen? Doris Salcedo’s Palimpsest (2013–17), an installation originally shown at Madrid’s Palacio de Cristal and recently at White Cube Bermondsey, sets the names of migrants who died trying to cross the Mediterranean into a sandy floor. Some of the names appear in lights, while others are made up of water droplets that seep through the ground. Together they disappear and reappear, creating a shifting surface over which visitors tread uneasily; all the more so, as they are warned by a gallery attendant not to actually step on the wet patches. Palimpsest fits with the themes of memory and trauma that run through Salcedo’s work in general. But the use of real names, gathered by the artist over several years of research, which included meeting with the families of the missing, pushes it into another context – that of the official monument. Such memorials have various functions, but they are most often used to fix identity (that of the nation, for instance, which owes its existence to these fallen soldiers, or pilots, or animals in war) and justify power, often that of the state that ordered these people to their deaths and then put up the monument. They are about forgetting, in order to establish a common narrative, as much as remembering.

Salcedo is playing with this familiar aesthetic, and you could read the title, Palimpsest, in two ways. One is that we’re surrounded by this sort of tragedy and that its stories are constantly being written and rewritten, never entirely readable or knowable. The other is that the stories are buried there if you know how to excavate them. But the particular way the names are used closes off the latter route. At a rough count, there were 200 or so, filling the gallery space floor. We aren’t told why these names and not others. If we can find out someone’s name, then why not anything else about them? By contrast, the Turkish artist Banu Cennetoğlu has produced a list of all 34,361 people (at the latest count) known to have died at Europe’s borders since 1993. This list, which includes names and nationalities, plus the location and cause of death, is printed on large sheets of paper and displayed in public locations – most recently, on building-site hoardings along a main road in Liverpool, as part of the city’s biennial. There, as well as being defaced with racist graffiti, the list has been repeatedly torn. Rather than restore it for a third time, the biennial and Liverpool City Council together with Cennetoğlu have decided to leave it there indefinitely, in its violated state. Violence is made visible twice over.

Killing in Umm al-Hiran, 18 January 2017 (still; 2017), Forensic Architecture. © Forensic Architecture, 2018

Other artists might aim to give their work a more explicit sense of usefulness, and this is arguably true of two works shortlisted for this year’s Turner Prize. Forensic Architecture’s Killing in Umm al-Hiran, 18 January 2017 (2017) most obviously aims for this, being an investigation into the killing of a Bedouin villager by Israeli police officers. The prolific group of architects, artists and investigators aims to use architectural techniques and technology to investigate human-rights violations, although the results are variable. As a survey exhibition at the ICA showed this year, the projects that work well combine aesthetic force and spatial analysis to give spectators a deeper understanding of how power is exercised in our age, as well as the tools to challenge it. Secret prison rooms are reconstructed using floor plans and the testimony of ex-detainees; official accounts of shootings are disproved by analysing the sound of the bullets being fired. But the ones that don’t work so well simply generate large amounts of data, attractively presented, to tell us something we already know.

Killing in Umm al-Hiran is on the stronger side: it analyses surveillance footage and reconstructs vehicle trajectories to undermine the official account of the incident. But it’s worth asking to what extent including this work in a prestigious art show furthers its political aims – or whether the greater effect is to allow a major institution to bask in the reflected glory without seriously interrogating its own politics. Another Turner Prize selection, three short films by Luke Willis Thompson that deal with state violence against black people, and the relationship between racism and the body, has already drawn criticism from some quarters for the perceived appropriation of black suffering. In September, members of the BBZ curatorial collective held a protest at Tate Britain, wearing T-shirts that read ‘black pain is not for profit’.

All four of this year’s Turner Prize selections have political overtones – and, taken together, seem like a statement by the judges about what artists and spectators should be thinking about in our current moment. They are also all largely video or film-based works, and substantial ones at that – it would take several hours to watch them all – that are to be watched first and responded to later. At Tate Modern, the current Turbine Hall commission takes a more interactive approach to a political theme. The Cuban artist Tania Bruguera has produced a series of interventions in and around the Turbine Hall – again, on the theme of migration – that seek to involve not only gallery visitors but also people who live in the surrounding neighbourhood. Bruguera has put together a committee of local residents to advise the Tate on how it can better interact with nearby communities. For the duration of the commission, the gallery’s Boiler House has been renamed after one of the locals, Natalie Bell – a quietly subversive touch, given the propensity of polluting corporations and wealth-hoarding businessmen for attaching their names to prestigious art projects.

Installation view of Tania Bruguera’s Tate Modern Turbine Hall commission in October 2018. Photo: Benedict Johnson; © Tate, London

The major installations play with some of the clichés of projects about refugees: big faces and big numbers. A giant photograph of a Syrian man, covered in heat-sensitive black paint, occupies a large part of the Turbine Hall floor. The more visitors walk, or sit, or roll around on it, the more the picture will be revealed. At the door of a side room, meanwhile, a gallery assistant waits to stamp the wrist of anyone who enters with a number that increases every time a new migrant death is recorded. Inside the room, we are told, is an ‘organic compound’ that will make people cry – what Bruguera calls ‘forced empathy’. This might, on the face of it, seem incoherent: a serious message mixed uneasily with the kind of ‘fun’ interactions visitors expect from the Turbine Hall, that most playground-like of galleries. But the interactions are, themselves, unsettling. We reveal the face of an individual only by crowding together and scuffing him with our feet; the side room, with its organic compound and serial number on the skin, evokes a gas chamber.

Sometimes, however, art can engage just as fully with the present by turning inwards, or looking backwards. Last year, John Akomfrah’s Purple continued his project of mining film archives to explore the historical processes of accumulation, expropriation and destruction that underlie climate change. (A new work, now showing at the Imperial War Museum, turns its attention to the role of African and colonial soldiers in the First World War.) The exploration of personal histories, meanwhile, can leave artworks open to new resonances and new meanings as the world changes around them. Naeem Mohaiemen’s Turner Prize exhibit includes Tripoli Cancelled (2017), a film based on his father’s experience of being trapped in an airport without a passport for nine days. In the film, an actor wanders around an abandoned airport, shaving and washing in the public bathrooms, or walking listlessly through the empty corridors. It now has a further layer of meaning: the abandoned airport is in Athens and, since the film was made, was itself used as a makeshift camp during the refugee crisis. (It was also the setting for Akomfrah’s film The Airport [2016]).

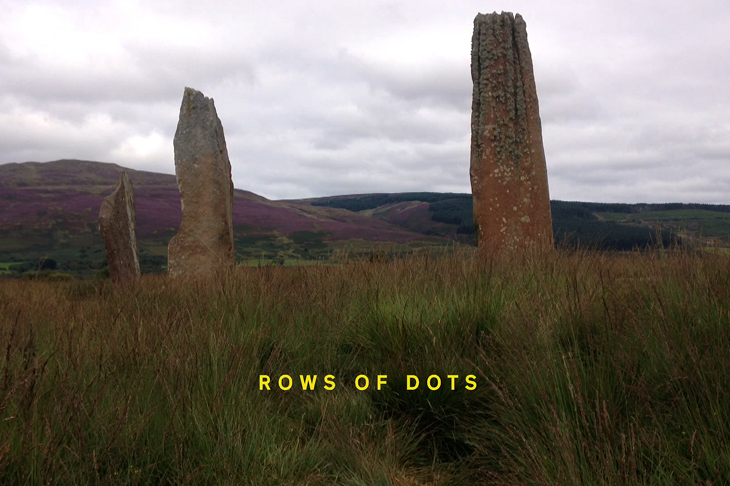

In the last of the Turner Prize selections, Charlotte Prodger’s BRIDGIT (2016), the artist uses an intimate and small-scale film-making technique – takes shot on an iPhone, mixed with a diary entry-like voiceover – to turn personal experience into a kind of mythology. The voice-over sections talk of being a queer woman moving through a sometimes uncomprehending or even hostile society, and of the waking-dreaming state that comes with prolonged hospital treatment. Meanwhile, the images range from the domestic (a pet cat, a view of the phone holder’s feet) to the northern Scottish landscape. Aberdeenshire, we are told, is the site of an unusually large number of megaliths – prehistoric standing stones. Gently, the film invites us to compare a personal web of meaning and narrative to the larger ways in which these are structured: across a land, or a people. The stones remind us this is never fixed for good: once, they must have meant something definite and obvious to the people who put them up. And if these things can shift, then perhaps our current problem is not one of seeing, or even of empathy, but of imagination – our ability to think beyond our current limitations. In this context, perhaps we need to worry less about art seeming topical and pay more attention to ways in which it can disrupt the everyday.

From the December 2018 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home