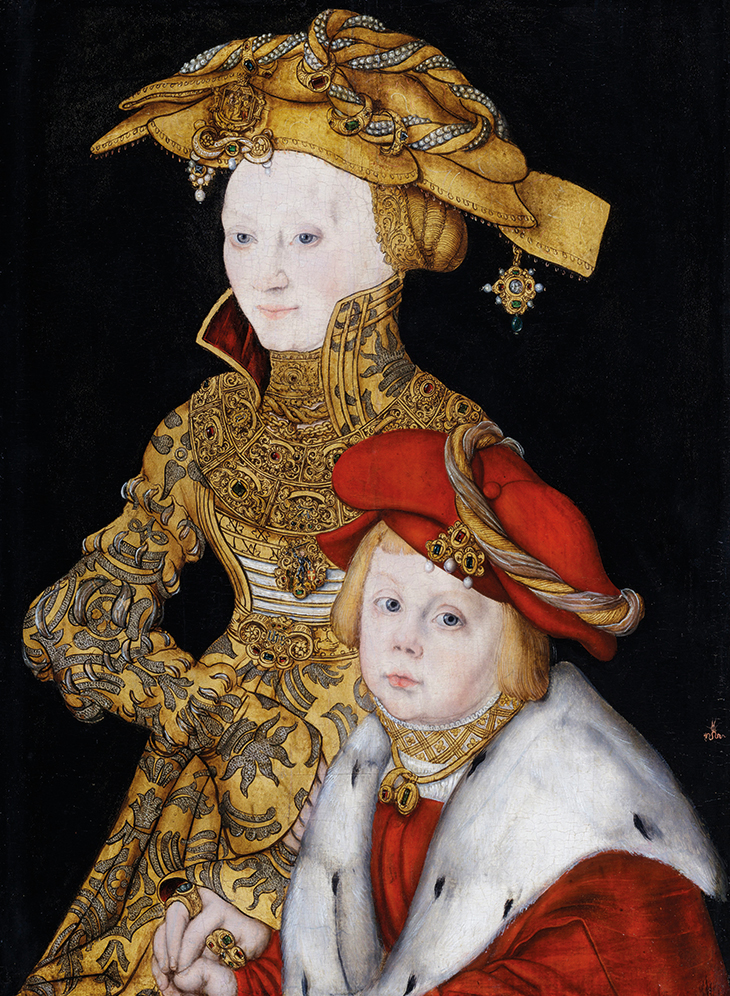

Chances are that if you think of Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472–1553), images of slender, sexy nudes will spring to mind. But on entering this exhibition visitors will find it is the clothing that steals the show. Cranach had an extraordinary ability to render textures, colours and folds; his velvets look thick and plush, gold chains lie heavily on shoulders, gems glint on the rings adorning gloved fingers. In the first room of this exhibition, the electors of Saxony, for whom the artist worked for 50 years, are arrayed in all their finery, resplendent against plain backgrounds. Their dynastic story is revealed in pictures: Frederick the Wise, the enlightened ruler who founded the University of Wittenberg, appears next to a diptych of his brother, Johann the Steadfast, and the latter’s son Johann Friedrich the Magnanimous. His son may be the doleful-looking child in a double portrait with his mother that hangs nearby. He is clad in crimson and ermine, while she wears a gold brocade dress and an extravagant hat dripping with jewels that look almost tactile. This painting is something of a rediscovery, as it languished in obscurity for years in the Royal Collection, thought to be by a 19th-century Cranach imitator until recent technical investigation revealed it to be the real thing.

Portrait of a Lady and her Son (c. 1510–40), Lucas Cranach the Elder and workshop. Photo: Royal Collection Trust; © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2020

Compton Verney has supplemented its own four Cranachs with loans from other British collections to illustrate selected themes in the artist’s life and work, displayed across four rooms. In the second room the narrative focuses on Cranach in Wittenberg, and his radical prints. By his forties, he was an upright citizen with his own coat of arms and a prosperous entrepreneur, with business interests that included a printing press, property and a licence to sell wine. The city had a flourishing artistic and intellectual culture and in 1517 become the epicentre of ecclesiastical controversy when Cranach’s friend Martin Luther nailed his 95 Theses criticising the excesses of the Catholic Church to the door of the cathedral. Cranach’s patrons may have been Catholic, but he worked for the Protestant cause anyway, providing illustrations for Luther’s German translation of the New Testament. One of them even showed the Antichrist wearing a papal tiara, although the elector asked him to remove it. Cranach also produced a set of satirical illustrations for a Reformation pamphlet that contrast the simple life of Christ with the corruption of the papacy through paired woodcuts. The messages are crude and direct: Christ expels the moneylenders from the temple but the Pope counts the coins in the papal coffers.

Portrait of Johann Friedrich the Magnanimous (1509), Lucas Cranach

the Elder. Photo: © National Gallery, London

Aided by his extensive workshop – at one point he employed some 10 assistants – and his ability to work at lightning speed, Cranach produced an enormous number of paintings: religious works, portraits, hunting scenes, allegories and mythologies. In 1509 he reinvented the German standing female nude – depicted by Dürer two years previously as Eve – as the pagan goddess Venus, accompanied by her son Cupid. It was evidently a successful formula: there are 27 known paintings of Venus and Cupid by Cranach and his workshop. These nudes are never completely naked, as they usually sport a fetching accessory lifted straight from Saxon court attire, such as a jewelled choker or elaborate hat. Unlike the sitters in Cranach’s male portraits, the goddesses are types rather than individuals, with the same elongated torsos and limbs, flowing ringlets, skin pale as marble and coquettish gaze. These erotic pictures were ostensibly a warning against female wiles and the temptations of seduction, but who would have been able to resist such temptation? The National Gallery’s Cupid Complaining to Venus (1526–27), which shows the winged boy protesting to a provocatively posed Venus that he has been stung by bees while stealing honeycomb, contains a verse telling viewers that sadness and pain are the price we pay for fleeting pleasure. The additional pleasure of this picture, however, lies in the minutely rendered bosky landscape in which a stag and hind take cover, with its distant rocky outcrop and lake. Cranach recorded the details of the natural world with poetry and accuracy. His friend Christoph Scheurl even claimed that he painted grapes on a table so naturally that a magpie attempted to eat them, and that dogs barked at his painting of a stag.

Cupid Complaining to Venus (1526–27), Lucas Cranach the Elder. Photo: © National Gallery, London

After Cranach left Wittenberg in 1550 to go into exile with the Elector of Saxony, the running of the workshop was taken over by his son Lucas Cranach the Younger (1515–86), who was so successful in imitating his father’s style that it is often hard to distinguish between their hands. Paintings by father and son have struck a chord with artists for centuries, and the exhibition ends with 15 modern and contemporary responses. Picasso, who always enjoyed pitting himself against the Old Masters, began producing variations on Cranach’s work in the 1940s, and drew his inspiration for the two prints on show here from a postcard and magazine illustrations. Cranach’s poetic landscape backgrounds were particularly admired in Germany in his lifetime and afterwards, and Raqib Shaw has taken his inspiration from them in his vibrant Reflections on a journey without a compass after Cranach (2019–20). The picture is a homage to Compton Verney’s glorious Lot and his Daughters (c. 1530), which shows the patriarch’s daughters attempting to seduce their father as the flames of Sodom and Gomorrah glow brilliant red in the background. Shaw himself becomes Lot, tormented by fantastical male figures. In the distance is an impressive conflagration; Cranach’s landscape has been deforested and modern refugees flee the eco-disaster. Michael Landy has taken his cue from the National Gallery’s Saints Genevieve and Apollonia (1506). The former was tortured by having her teeth pulled out, and Landy’s enormous mechanical Saint Apollonia (2013) invites you to have fun operating a foot pedal that makes her hit herself in the face with pliers. It’s a shame that the painting isn’t here beside it.

Lot and his Daughters (c. 1530), Lucas Cranach the Elder. Photo: © Compton Verney

It is Cranach’s distinctive female nudes that have the most obvious contemporary legacy. John Currin’s Honeymoon Nude (1998) blends the curiously boneless physiques of Cranach’s goddesses with contemporary magazine imagery to disturbing effect. Ishbel Myerscough reacts against Cranach’s idealised vision of female anatomy but adopts his clarity and directness to portray the fleshy reality of women’s bodies. But the last word goes to Claire Partington and her two ceramic figurines, which provide a defiant riposte to Cranach’s coy and compliant creations. Her Venus and Cupid (2020), based on Compton Verney’s Cranach of the same name, is accompanied not by a playful toddler but by a snarling dog. She goes one step further with her Judith (2020), a machete-wielding heroine who stands in triumph with one foot on a severed head – not that of Holofernes, but of Cranach himself.

‘Cranach: Artist & Innovator’ is at Compton Verney Art Gallery & Park until 3 January 2021.

From the September 2020 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home