Overseas holidays from the UK are out, it seems – unless you want to spend £5,000 more than you’ve budgeted. And by now, every hotel room in Brighton and cottage in Cornwall is probably booked up until the winter. Oh well. Here are some cultural corners of the country that you could explore instead, picked out by our editors.

Aberdeenshire

Locked down in London, I’m craving space even more than art, and dreaming of wild places. It would be wonderful to go to Catterline, the small fishing village on the north-east coast of Scotland. With its views of the expanse of the North Sea and the raking clarity of light, the village drew a number of artists in the mid 20th century, Joan Eardley, Angus Neil and James Morrison among them. A few miles north is Aberdeen, whose inhabitants I’ve sometimes envied during lockdown – the shimmering grey of its many majestic buildings hewn of granite makes it one of the finest cities in the country for wandering around, without any other agenda than looking. Samuel Reilly

Catterline Bay. Photo: Leonardo Gentile/Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Leeds

At the turn of the 20th century, the Leeds Art Club, under the aegis of the art historian Herbert Read and the painter Jacob Kramer, championed the work of Kandinsky and other European Expressionists before anyone else in the UK had cottoned on to them; since then, the city has continually renewed its reputation as a petri dish of the avant-garde. The Leeds College of Art launched the careers of Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth in the 1920s; in 1971, Patrick Heron called the college ‘the most influential art school in Europe since the Bauhaus’, and since then Griselda Pollock has established the School of Fine Art as a centre for radical feminist study. Unsurprisingly, the municipal art gallery boasts a collection of 20th-century British art that is second to none, while the nearby Henry Moore Institute has become a wonderful place both to see and to study sculpture. Outside the city, the Hepworth Wakefield – a necessary pilgrimage for fans of the sculptor – is celebrating its 10th anniversary this year. And if the thought of crowding into galleries gives you the heebie-jeebies in these socially distanced times, the spacious grounds of the Yorkshire Sculpture Park nearby might almost have been designed for you. SR

The Family of Man (1970), Barbara Hepworth, installed at Yorkshire Sculpture Park. Photo: © Jonty Wilde

Plymouth

For me, summer holidays have always meant south Devon. When I was a child, that sometimes included Exeter and it often meant traipsing around stately homes. But we never went to Plymouth, except perhaps once when it was raining (it was often raining) to see Smeaton’s Tower, the lighthouse on Plymouth Hoe. Anyway, last year I did Plymouth a couple of times – and this summer I’m going back. You’ll need a day for the post-war architecture, much of it jaded but now at least increasingly lauded for its historical, architectural and civic significance. My pick of it is the pannier market, built by Walls and Pearn for Plymouth City Council in 1959–60 and with the market stalls dwarfed under a vast, wide roof that is probably as august as concrete gets. And then there’s the Box, the city’s new civic museum, which I wrote about here and which has fascinating permanent collections and a big show on local boy Joshua Reynolds coming up this summer. For a little architectural dérive, if you’re driving: head to Devonport to see the Odd Fellows Hall, one of only two Egyptian-style houses in England (the other is in Penzance), then across the Tamar for Saltash Library – recently listed and, said its architect, ‘the most Corbusier building in Britain’. Thomas Marks

Inside Plymouth’s pannier market. Photo: Thomas Marks

Colchester

How about a long weekend in Colchester? A bit of Romans in Britain – until Boudica came knocking, Camulodunum was the capital of Roman Britain – and Saxon stuff up the road, past Ipswich, at Sutton Hoo. There are plenty of big horizons, little changed from how Constable saw them, along the River Stour (and there’s an Alfred Munnings museum in Dedham, too, if Munnings is your thing). And south of Colchester is Mersea Island, which has no great artistic claims that I know of, but does have excellent oysters: you can’t go wrong with a dozen Colchester natives at the Company Shed. TM

A Mill Near Colchester (1833), John Constable. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Portmeirion, North Wales

My annual winter trip to Wales usually consists of long walks and hikes in national parks, sampling the local food markets and cooking large roast dinners. After a year of doing little else, however, I’m keen to explore new horizons. On my list? The Mediterranean-inspired holiday village of Portmeirion on the coast of North Wales, built between 1925 and 1975 by the architect Clough Williams-Ellis. The village, with its eclectic mix of Riviera-style houses and plazas, medieval ruins and a Victorian castle converted into a luxury hotel, has been described as ‘a sort of architectural folly’ in itself. It was also famously the filming location for the cult sci-fi show The Prisoner (1967), in which an abducted British spy is held captive in the village. I can think of worse places to be trapped. Gabrielle Schwarz

Photo: Mike McBey (CC-BY-2.0)

Margate

In recent years artists have flocked to Margate, spurred by low rents (in comparison to London at least) and a growing scene of galleries and artist-run spaces. Turner Contemporary, which opened in 2011, is currently undergoing a major expansion, and last year Tracey Emin, who grew up in the seaside town, took up permanent residence in a new home-studio which she plans to turn into a museum after her death. But Margate also has a rich cultural past. Walking along the seafront on a rainy day, you might stop to take cover under the Nayland Rock promenade shelter, a Grade II-listed structure built around 1900, thought to be the spot where T.S. Eliot sat and drafted lines for The Waste Land in November 1921: ‘On Margate Sands. / I can connect / Nothing with nothing…’. And then, some 20 minutes’ walk away, there’s the Shell Grotto, a mysterious underground warren covered in shell mosaics and apparently ‘discovered’ in 1835. No one knows why or when it was built. GS

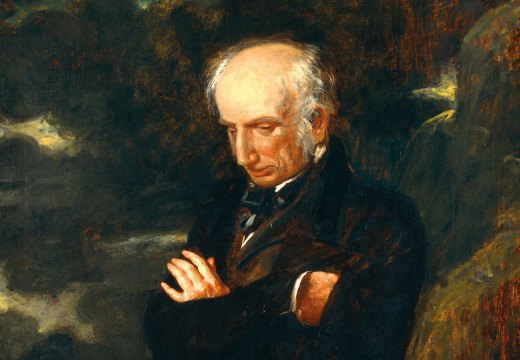

Lake District

With its soaring peaks and sweeping valleys, the Lake District is a perennially popular tourist destination, but it has also been home to quite a few writers and artists, whose former residences have become sites of pilgrimage for their admirers. Wordsworth lived for many years in the village of Grasmere – including a decade at Dove Cottage, now a house museum with an adjoining gallery displaying artworks and artefacts relating to Wordsworth and his fellow Romantic bards (recently expanded as part of a £6.2m redevelopment and set to reopen this spring). You can also visit the homes of John Ruskin and Beatrix Potter – or, if in the mood for something a little more avant-garde, Kurt Schwitters’ Merz Barn, the woodland studio the German refugee artist started building in 1947, the year before his death. GS

Dove Cottage in Grasmere. Photo: Wordsworth Trust

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home