There is something so vital about the photographs of Edward Barber. They simmer with life, closely intertwined with a social context – death, inequality, defiance, unity – that belies their external sheen. Barber bludgeons these histories into something quite ordered but, even here – when he has digitised and blown up his photographs into large black-and-white prints for an exhibition at the Imperial War Museum – there is a sense of mischief and mayhem, too.

A sense of what Barber calls ‘organised chaos’ permeates this intimate display. His Peace Signs body of work features more than 40 images by the 61-year-old photographer, which attest to the various creative outcomes of the anti-nuclear movement in 1980s Britain: protest, performance, fashion, mass mobilisation, picketing.

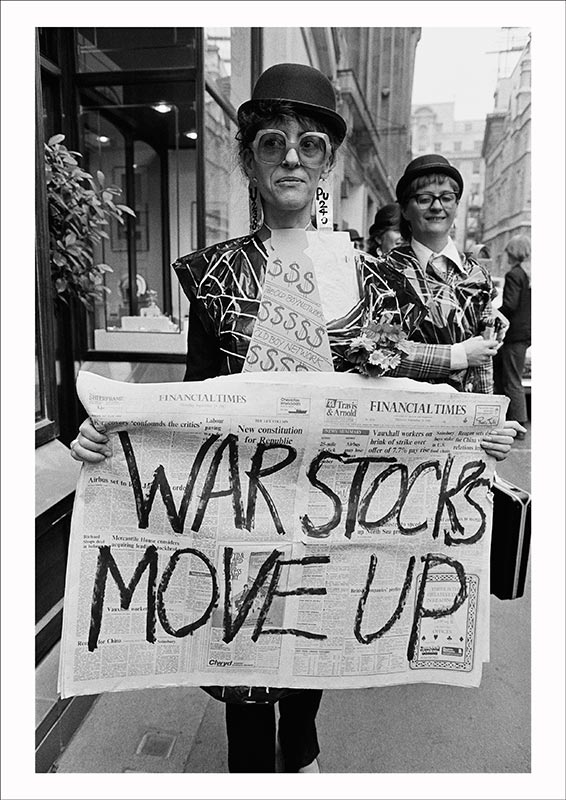

‘Stop the City’ protester at the Bank of England, City of London (1983), Edward Barber. © Edward Barber

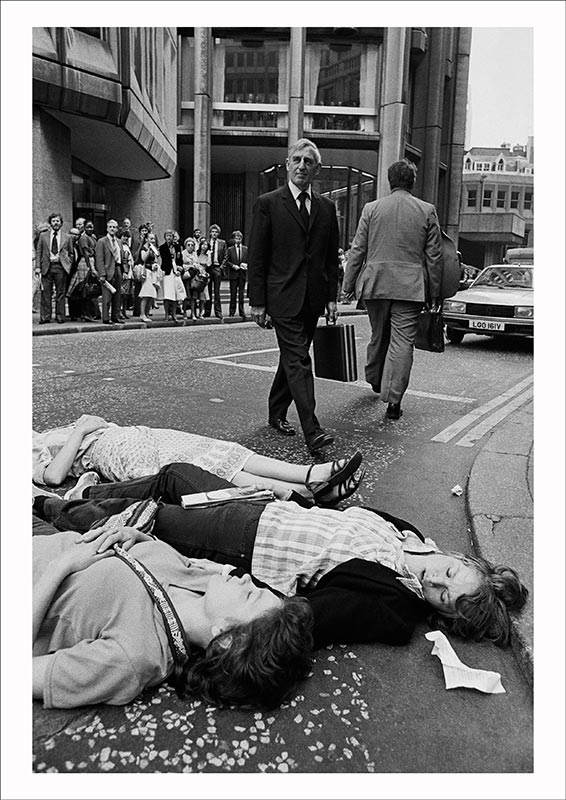

We see bobbies on the beat carrying prostrate activists, and floppy-haired youngsters beside stern-looking seniors. We see 30,000 women form a nine-mile-long human chain around RAF Greenham Common in 1982 (the role of women in this movement is striking), while signs in other photographs tease: ‘Take the toys away from the boys.’ At times the images are surreal, even dystopic. One man wears a paper-bag hat with instructions on what to do in the event of a nuclear attack. In another photograph, a policeman gladly poses next to a van while a sandalled foot sticks out from below the vehicle. Does he know? Are they alive? All valid questions.

In mounting the show Barber has decided to separate the experience of viewing the images from their political and historical setting. There are no labels beside the photographs to provide the time, place or further information. In fact, Peace Signs eschews any temporal or thematic grouping, in an interesting attempt to evoke the spirit of the era – or, as the curators put it, to present ‘a contemporary reinterpretation’. It’s a gesture that Barber takes beyond the frame, too: the walls of the gallery space have been painted a cautious canary yellow; dramatic lighting gives it a radioactive glow; the benches have had CND logos drilled into them.

Greenham Common protesters stage a Die-in outside the Stock Exchange during the morning rush hour as U.S. President Reagan arrives in Britain, City of London (1982), Edward Barber. This was the first major London event initiated by the Greenham Common women and coincided with the Falklands Conflict. The Die-in symbolised the one million who, it was argued, would die in a nuclear attack on London. © Edward Barber

Not until the final corner of the exhibition do we encounter Barber’s Mind Map of Anti-Nuclear Protest, a new commission, which is a splurge of thick marker pen in blue, black and red. It’s like a schoolchild’s notes for a history exam, with nearly 200 elements, all scribbles and jaunty arrows connecting ideas: a history of the nuclear age from before the Cuban Missile Crisis up to Jeremy Corbyn. In the exhibition material, Barber writes: ‘I see this as preventative photography. The photographs here are both a celebration and a warning.’ This section is a triumph of both intentions.

It is a shame there is not space for more of the same. Barber brilliantly captures the perms, punk rock, and ’60s-tinged Americana style of the period, and makes observations with which the social documentarian Martin Parr would be pleased. A baby’s pram is repurposed to carry a fake missile. One slick gentleman seems too cool to hold a peace sign, leaving the job to his son. But on the whole, it is a very sincere movement, which uses life as a doodle pad. Barber records the badges and witty banners which make up their unique strand of folk art. It’s as if Grayson Perry had been born a photographer.

One shot that lingers in the memory is of a policeman, who is holding his helmet and looking perplexed. Perhaps Barber is asking, with the looming threat of a renewed Trident programme, why aren’t more of us reacting this way?

‘Edward Barber’ is at the Imperial War Museum, London, until 4 September.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home