About a decade ago, I was brought in to help write the biography of two largely forgotten painters affiliated with the artistic set that had haunted the Colony Room in Soho in the 1950s. Their lives had yielded a bonanza of anecdotes: they had known everyone from Bacon to Spender to Noel Coward and even, allegedly, stolen a painting from Lucian Freud. Yet from the beginning, we were very conscious that the project had to add up to more than an exercise in namedropping. In order to justify itself as a story worth telling, we decided, it had to fulfil two functions: to enrich, or even challenge the reader’s understanding of the contextual social and art history; and to make a convincing a case that our subjects’ (frequently impressive) work demanded re-examination. If you think that sounds simple, think again.

Anyone tasking themselves with the biographical ‘rediscovery’ of such bit-part players will burden themselves with similar criteria, and probably come to the conclusion that peripheral figures in art history, more often than not, exist on the periphery for a reason. Take the case of Edward Brezinski, the subject of Brian Vincent’s peculiar documentary Make Me Famous. Brezinski, a Neo-Expressionist painter active in Manhattan’s East Village in the early 1980s, was as peripheral as they come. So marginal, in fact, that even his family members seem miffed when Vincent doorsteps them. ‘I don’t know how Edward could possibly be considered significant or important enough to warrant this type of inquiry into his past,’ his cousin Ted exhales at one point.

Self-Portrait (1976), Edward Brezinski. © Edward Brezinski

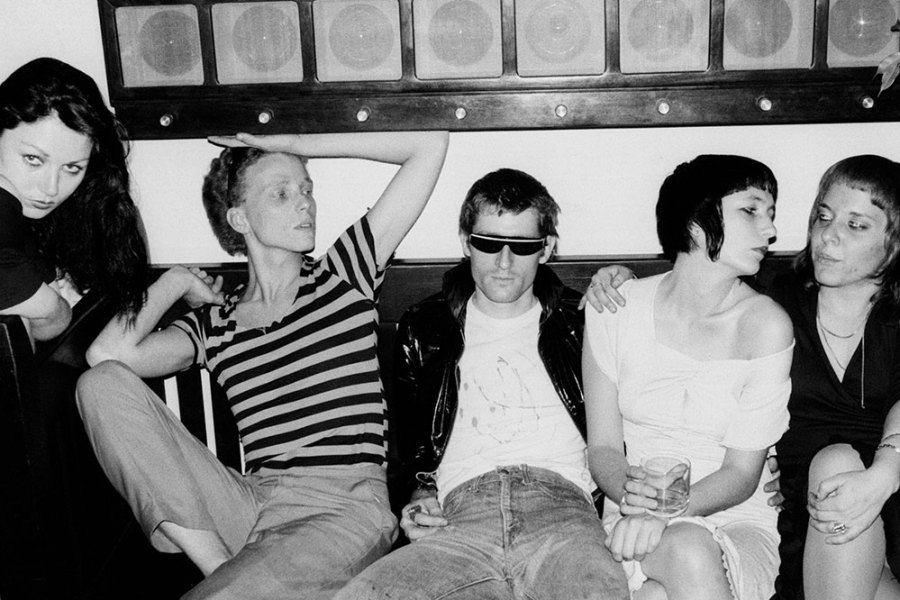

No great claim is made about Brezinski’s art (the best an interviewee can come up with is that it is ‘very typical’ of its style), nor does he come across as a particularly sympathetic figure. As a mutual acquaintance told me last week, Brezinski was ‘a terrible, terrible drunk’ – the evidence for which builds up steadily over the course of the film. He repeatedly gets into fights, throws a glass of wine in the gallerist Annina Nosei’s face, alienates all but the most loyal of friends. He fetishises the archetype of the ‘starving artist’, yet seethes at others’ success. You almost will him to keep failing.

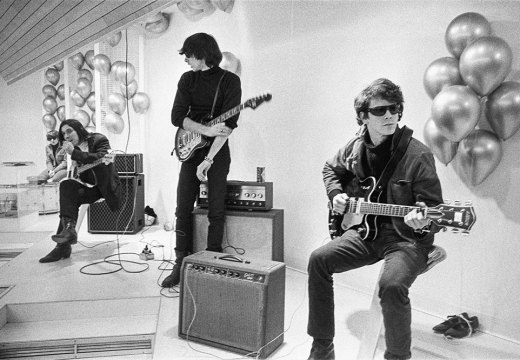

Where the film does justify itself, however, is in communicating the texture and atmosphere of the East Village’s consciously-defined ‘scene’. At the turn of the ’80s, the now-bijou district was a wasteland of semi-derelict tenements and abandoned storefronts. Naturally, it attracted aspirant artists by the bus-load: McDermott & McGough, Kenny Scharf, Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat, all set up shop in the neighbourhood – sometimes literally. Artists set up galleries in their apartments and in vacant shops, exhibiting each other’s work. Profit was a secondary concern; the point was to get yourself noticed by the ‘serious’ gallerists a dozen blocks west in SoHo. ’There was no emphasis on making money,’ the late Duncan Hannah recalls, ‘because no one had any money’.

Brezinski set up his own space, the Magic Gallery (‘the most stupid name imaginable’, says Peter McGough) in his apartment on East 3rd street, showing all comers. Vincent has unearthed a wealth of grainy home-movie footage of the various happenings, openings and performances it held: we see Gary Indiana reciting a bitchy screed about a perceived slight from David Wojnarowicz; an ‘intense’ Miguel Pinero poetry recital at which attendees turn eyes to the floor, wishing they were literally anywhere else; and Brezinski himself, failing to hawk one of his portraits. Everyone looks freezing, sweaty, filthy. You can almost taste the cheap wine.

Edward Brezinski and CLICK models, photographed by Jonathan Postal in October 1984 for NY TALK magazine. Photo: © Jonathan Postal

Nevertheless, they all behave like stars-in-waiting. Brezinski, who threw work at any group exhibition going, seems to have anticipated that the recognition he craved lay just around the corner. But Neo-Expressionism, with its angsty post-punk neuroses, was on the way out: newcomers such as Jeff Koons and Haim Steinbach were making waves with glossy Pop conceptualism that better catered to the tastes of the collectors of the time. And as Robert Hawkins, interviewed here, puts it: ‘You couldn’t just find it in the garbage and paint on it… you needed money to do those things.’

‘Those things’, however, did at least enable Brezinski to grab his 15 minutes of fame. Having ligged his way into Robert Gober’s first big exhibition at Paula Cooper Gallery in 1989, he encountered a work consisting of a bag of doughnuts presented on a plinth. Outraged at the keen pricing of the edition, he reached into the bag, picked out a doughnut and performatively ate it, crumbs rolling down his chin. Gober, alarmed, ran across the gallery to tell him the donuts had been treated with formaldehyde. ‘He went to the emergency room, they said “Go home, you’re fine,”’ Gober recalls. ‘Instead of going home, he calls Page Six in the New York Post, and then the Associated Press picked up on [the story] and it went around the world.’

It was the closest Brezinski ever came to receiving recognition. By 1990, the East Village scene had been hollowed out by rising rents and AIDS (addressed here with mystifying brevity). Brezinski left, first for Berlin, where he lived in miserable poverty and routinely got himself beaten up, then for France. He died in Cannes in 2007. The news may have come as a surprise to even close family in Michigan, who had known nothing of his whereabouts, nor at this point whether he was alive or dead. This sad, 17-year coda is dealt with by way of a wild-goose chase on the part of the film-makers: they initially fail to find his death certificate, leading them to speculate that the subject may have faked his own death. The ambiguity is quickly attributed to clerical error.

It’s difficult to tell whether the film’s makers are consciously trying to channel the amateurishness of the East Village set. Cut at breakneck speed – you never quite shake the sense that you’re watching a trailer for the film, rather than the film itself – to a throbbing electronic soundtrack, it feels as if it’s in a hurry to prove a point that is never articulated. The milieu, to give Vincent credit, is at times vividly evoked, yet Brezinski remains elusive throughout. Like cousin Ted, I was left none the wiser as to why this documentary was ever made.

Make Me Famous (dir. Brian Vincent) is currently screening in UK cinemas.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home