From the June 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

El Greco’s influence on Picasso’s early work is well known but, as Carmen Giménez – curator of an upcoming exhibition in Basel – explains to Apollo, the modernist’s debt to the Old Master was lifelong.

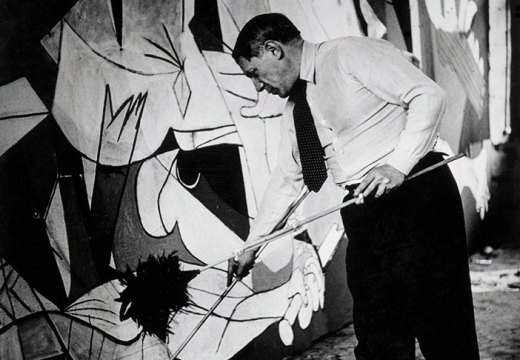

When Picasso (1881–1973) was 16 years old, his father sent him to the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando in Madrid – the most important art school established in the 18th century, which was extremely academic in its teaching. Bored by these lessons, Picasso began instead to make daily visits to the Museo del Prado. It was there that he discovered the work of Diego Velázquez and, especially, El Greco (1541–1614), who fascinated him instantly.

At the time, the achievements of El Greco had been virtually forgotten by the establishment – and he was particularly detested in Spain. In the year Picasso was born, 1881, the director of the Prado wanted to throw away the El Greco paintings in the museum’s collection. But at the end of the 19th century, painters were looking for new ideas; new ways of representing the world. Picasso was not alone among his friends in appreciating the work of El Greco in this regard – his contemporary, Ignacio Zuloaga, acquired The Vision of St John (c. 1608-14; now owned by the Met), among a number of other works. While copying El Greco, another friend of Picasso who accompanied him to the Prado recalled how they were called ‘Modernistas’; even Picasso’s father, a painter himself, told them, ‘You’re taking the wrong path.’ But with his peculiar capacity for understanding the essence of the older painter, Picasso came very quickly to think of El Greco as his hero.

What Picasso valued above all in El Greco was the freedom that the artist personified. We are very lucky, I think, that Philip II did not hire El Greco to work at his court; in 1576, attracted by the construction of the Royal Monastery of El Escorial, El Greco moved to Spain where he tried to secure the king’s patronage. He presented the king with a painting, Adoration of the Name of Jesus (1577–79), but unfortunately it was not well received. Privileging style over content, El Greco had violated the highest standard of Counter-Reformation taste.

Although it might have been interesting to see how El Escorial turned out with El Greco at work on it, the fact is that he remained independent as the premier artist in Toledo, counting among his friends a number of cultivated, intelligent writers and thinkers. (Like Picasso, he did not spend much time with fellow painters.) When one thinks of Velázquez – he left us no record of his thoughts about El Greco, but when he died three portraits by the painter were found in his studio – he was always bound by the demands of the king, his master. In the relative isolation of Toledo, El Greco was free to do pretty well whatever he liked. He was able to forge a style of his own, one that struck a unique balance between the post-Byzantine tradition of his earliest training in Crete and the techniques he had learned in Italy.

You see the fruits of this freedom in El Greco’s masterpiece, The Burial of the Count of Orgaz (c. 1586–88). The lower section is comprised of portraits – and many of these subjects appear in later paintings – but the vision of heaven represented in the upper section of the painting is remarkable for its total disregard for perspective; instead, what is represented is freedom. Picasso saw this painting at the age of 19, on the first of many trips to Toledo. He also saw El Greco’s The Visitation (c. 1610–14) – on which he modelled his own painting Two Sisters (The Meeting) in 1902, a work which has come to be seen as one of the most significant paintings of his Blue Period (1901–04).

From then on, El Greco was always present in Picasso’s life. Much has been written and studied about El Greco’s influence during the Blue Period but in reality El Greco accompanied Picasso throughout his career.

The Penitent Magdalene (c. 1580–85), El Greco. Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City

To me, Cubism seems to have been born with El Greco – from whom Picasso took a certain conception of space, of colour and particularly of distortion. Turning to one of the striking comparisons in the exhibition – of El Greco’s The Penitent Magdalene c. 1580–85, in the collection of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, and Picasso’s Seated Nude (1909–10) in the collection of the Tate in London – these three aspects are particularly helpful in allowing us to draw analogies.

Seated Nude (1909–10), Pablo Picasso. Tate, London. © Succession Picasso/DACS, London 2022

One of the key techniques used by El Greco to provide the sense of distortion one finds in his images was identified by his contemporary, Francisco Pacheco, the teacher and father-in-law of Velázquez who wrote a landmark textbook called The Art of Painting. When Pacheco saw El Greco’s work, he was horrified by what he termed El Greco’s crueles borrones (‘cruel smudges’) – immediate brushstrokes that cut across the surface of the painting. Pacheco was of his time, while El Greco was ahead of it and this way of handling paint was something that only began to be reappreciated in the 19th century. Cézanne in particular looked closely at El Greco and it was part of Picasso’s genius to understand what El Greco was trying to do with his crueles borrones.

In The Penitent Magdalene, El Greco layers patches of coloured brushstrokes, rather than relying on lines, to define the form and provide depth. It was a technique that relied on internal structure – precise, complex and perfectly planned. Nothing is left to chance. This is clear especially in the sky and the rock behind the figure, and also in El Greco’s handling of the figure herself: her blouse, her hair. He uses an almost single chromatic range of grey and silvery blue in his palette, which he applies with such nuance that the monochrome becomes virtually polychrome. His tones range from purest white to deepest black and his shapes are arranged in folds that are almost abstract.

Picasso’s Seated Nude was painted in 1909–10, making it an early example of Analytical Cubism, of which the high point is generally taken to be 1911. Analytic Cubism functions in particular by highlighting the two-dimensionality of the canvas. Neither flat nor three-dimensional, Picasso’s subject here is broken down to geometric fragments that gradually accumulate, building up an image. It creates an illusion of relief and depth that relies less on perspective and more – in a similar fashion to El Greco’s crueles borrones – on shading and the difference between dark and light, reducing his palette to a near-monochromatic range, with a preference for browns, greys, and creams.

Although I don’t believe that Picasso was consciously modelling this nude on the work by El Greco, putting the two paintings together is nonetheless extraordinary; the similarity in composition and structure bringing to the fore the similarity of the two painters’ use of tone. What is evident in the relationship between the two is the ways that El Greco’s piece infiltrated modern painting from its inception.

© Succession Picasso/DACS, London 2022

It ought to shock us to see the El Greco beside the Cubist painting. The Magdalene is beautiful; she is looking at God. In the Seated Nude, the face is completely obliterated. Yet she has exactly the same tenderness as the Magdalene. Looking at the formal aspects of what Picasso is taking from El Greco – comparing the brushstrokes, spatial arrangements, tonalities – changes the emotional sense of what we’re seeing. Working closely with El Greco has given me a much deeper understanding of Cubism – and I think that looking at El Greco through Picasso’s eyes gives us new insights into the older artist, too. There is the astonishing moment in The Penitent Magdalene where El Greco effectively cuts a hole in the sky, playing with the clouds around it in a way that is completely abstract, as the comparison with Picasso underlines.

The influence of El Greco on Picasso continued long after Picasso had left Cubism behind – in particular, the inventiveness of El Greco’s portraits remained a touchstone throughout Picasso’s career. In the final part of the exhibition is a work from 1967, The Musketeer, painted when Picasso was 86 years old and recovering from an operation. On the back of it, Picasso included a signature which reads ‘Domenico Theotocopulos van Rijn da Silva’ – an amalgam of the names of El Greco, Rembrandt and Velázquez. I think what this tells us is that Picasso understood that he could never be caught in one style for too long – he had to keep moving, keep looking, keep researching the art of the past. That is what made him unique.

As told to Samuel Reilly.

Carmen Giménez is an independent curator.

‘Picasso – El Greco’ is at the Kunstmuseum Basel from 11 June–25 September.

From the June 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Has the Fitzwilliam lost the hang of things?