Most great designers have chairs which in some way define them – Le Corbusier, the Eames, Mies van der Rohe, Eileen Gray. These chairs are, in their own way, elegant and practical; they have a certain cachet. By contrast, Enzo Mari, who is currently the subject of a retrospective at the Design Museum, has the Sedia P (‘Chair P’). It’s a lumpy, unsubtle, seemingly naive design. If a child were to sketch a chair this is what they’d draw: four legs, a seat and a backrest. It’s not a chair you often find in the pages of Architectural Digest.

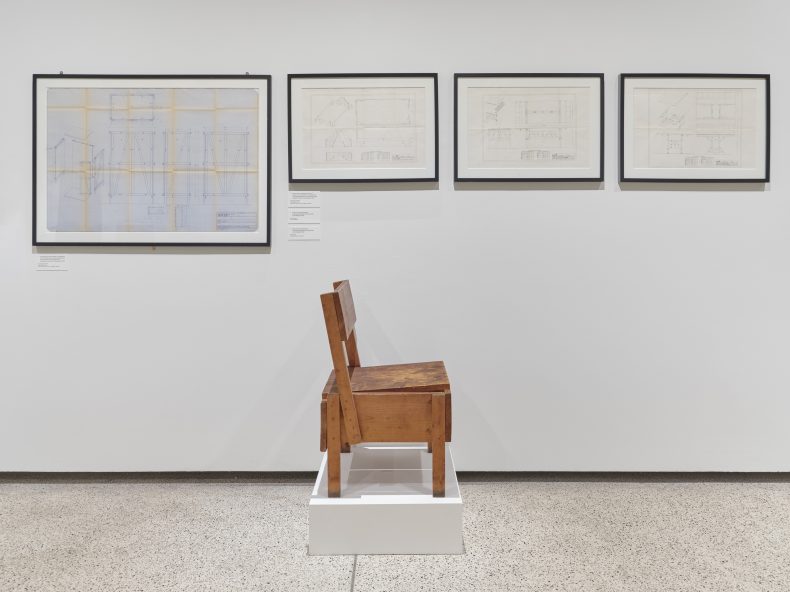

Installation view of Sedia P (1973) by Enzo Mari at the Design Museum. Photo: © Eva Herzog; courtesy the Design Museum

Throughout the show, first curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist for the Triennale Milano in 2020, the argument is made that for Mari, the process, not the end product, was the point. A small run of vases created for the high-end German porcelain manufacturer KPM, for instance, involved taking the ceramic pipes that KPM made for industrial insulation purposes but didn’t sell commercially, and smashing them with a hammer. The smashed end of the pipe gave each vase an original and unreproducible shape. It was a way of creating something unique from mass-produced materials.

Model A (1958) from the Putrella series of iron section bar containers by Enzo Mari. Danese Milano. Photo: Fabio and Sergio Grazzani

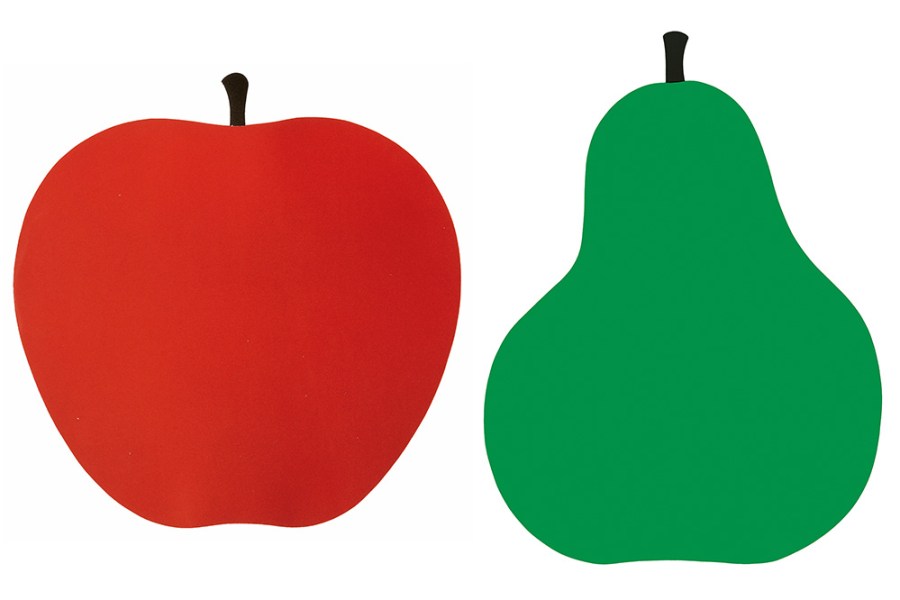

Mari’s designs, the exhibition suggests, tended towards the simplest solution. Huge prints of an apple and a pear, designed in 1961, stand on either side of the entrance – Mari’s attempts to create the definitive representation of these fruits. Though they look like they might belong in a child’s alphabet book, these are striking prints, and unmistakably an apple and pear. In using just two blocks of colour, they are easily reproducible, and still available today.

No. 1: The Apple (1961), from the Nature series by Enzo and Elio Mari. Photo: Danese Milano

An early relationship with the Milan-based manufacturer Danese gave Mari licence to research various techniques and processes to explore his simple approach to design. His creations for Danese were fairly rudimentary. Iron bars and plates were cut, welded and bent into different shapes to make simple containers. Each one looks a bit like a test piece; evidence of the welding is often prominent and the original ‘H’ shape of the iron girder is usually still visible. The simplest iron piece, from 1958, is a girder that has been bent slightly at both ends to create a long dish-like container. It is still quite obviously an industrial girder, but has had just enough intervention from Mari to put it to new use.

No. 2: The Pear (1961), from the Nature series by Enzo and Elio Mari. Photo: Danese Milano

Which brings us back to the Sedia P. It’s very clear that this chair is made from 13 chunky lumps of wood; even the nails that hold them together are visible. Mari came to this design – and the idea for the ‘Proposta per un’autoprogettazione’ (‘Proposal for a self-design’, 1973), which included similarly rustic designs for tables, beds and storage units – after his plan for a sofa bed for mass production was rejected by retailers. Ironically, the object Mari had envisaged was so cheap to produce that retailers didn’t want to sell it – they felt consumers wouldn’t trust something so affordable. Mari is quoted in a wall label as being accepting of this, but he refused to accept the criticism levelled at his designs by the leftist groups that declared their preference for the beds made by Italian artisans – even if those beds, with their marble bases and water mattresses, were made for Arab oil magnates. Mari felt that the best way to reason with these critics, with whom he felt a political affinity, was to design furniture that was even more democratic – furniture that could make an artisan of anyone. So the ‘Self-design collection’ was born. Anyone, ‘excluding industries and sales persons’, could write to Mari to request the design booklet free of charge, save for the cost of postage. Mari asked merely that people send photos of their efforts, and of variations on the designs they might adapt themselves. He received thousands of responses and kept them in his archive.

When judging design objects, people often give considerable weight to the aesthetics of the objects and clear markers of the designers’ mastery of their craft. Mari, however, found a clever way to do things differently. He empowered others to make their own objects, so that rather than simply admiring someone else’s craft, they could understand and practise design on their own terms.

‘Enzo Mari’ is at the Design Museum in London until 8 September.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home