Our understanding of the history of the emperors who ruled over late medieval Ethiopia is still quite fragmentary but, as far as we can tell, life at their courts was marked by violence, betrayal, and power struggles. Perhaps the most prominent among these rulers, who belonged to a house that rose to power in 1270 and traced its descent back to King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, was Zar’a Ya‘eqob (r. 1434–68). What is known about his reign has hitherto been gleaned mostly from Ethiopic texts in ancient parchment manuscripts, some still preserved in the country’s hard-to-access monasteries, others now in Western collections. However, objects such as icons and wall paintings can also provide insights into the culture and society of this period and, through an interweaving of text and image, present a fuller account of one of the most important rulers in Ethiopian history.

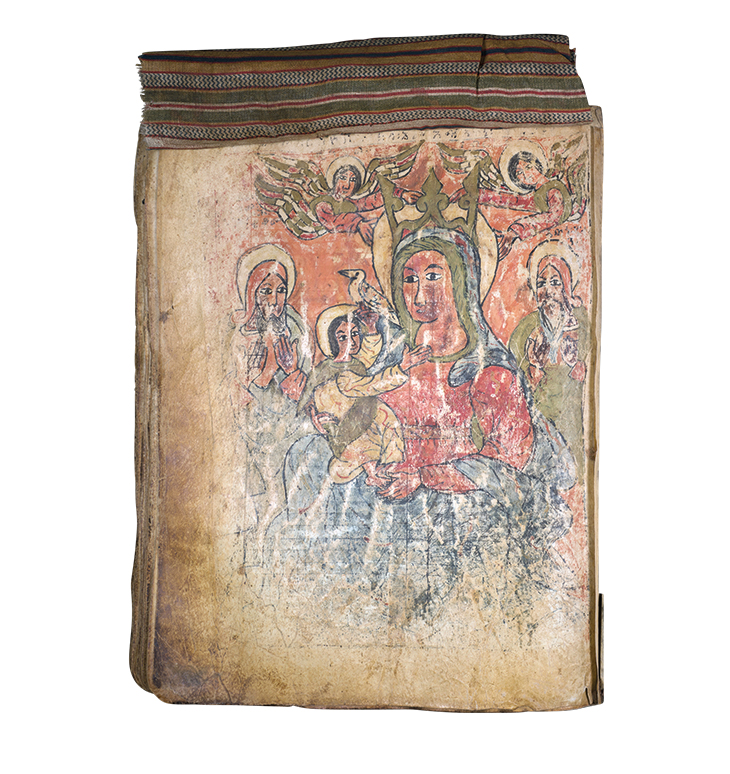

A retelling of his life could begin with a late 15th- or early 16th-century Ethiopic manuscript now kept in the Giovardiana library in Veroli, the frontispiece of which bears an image of the Virgin and Child. It contains a collection of texts known as the ‘Miracles of Mary’. The nucleus of these stories about the miraculous interventions of the Virgin, which vary in number and content in each manuscript, was written in 12th-century France, but the work was translated into Arabic in the 13th century, and into Ethiopic at the end of the 14th century at the behest of Emperor Dawit II (r. 1382–1413), Zar’a Ya‘eqob’s father. Because the Ethiopic version was soon enriched with local traditions about the Virgin’s miraculous powers, it is a valuable source for understanding the political and religious history of Ethiopia from the 15th century onwards.

One of the stories in the Giovardiana manuscript describes the miraculous birth of Zar’a Ya‘eqob. According to this text, his mother, Queen Egzi’ Kebra, had miscarried her first child and almost lost him, too. Seized by spasms five weeks into her pregnancy, she asked a priest called Athanasius to pray to the Virgin Mary on her behalf, after which her pains ceased and about eight months later, in 1399, the future emperor was born. Local traditions make this the first of many miraculous interventions of the Virgin Mary into the life of Zar’a Ya‘eqob, whose devotion to her reached the point of zealotry.

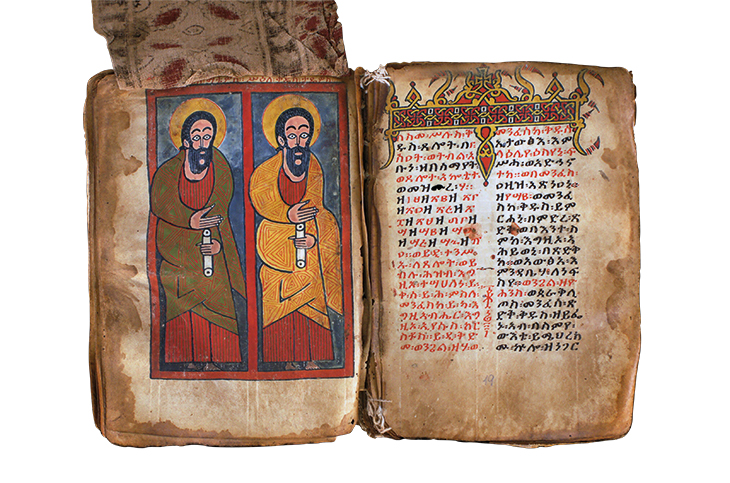

The apostles Matthew and Thaddeus (early 15th century), unknown artist, Ethiopia. Dabra Abbay monastery, Tigray region. Photo: Michael Gervers

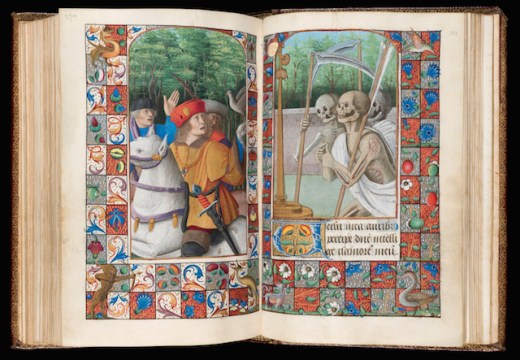

Moments after giving birth to Zar’a Ya‘eqob, the Giovardiana manuscript records, the queen used blades of grass to draw a cross in the name of Mary on the infant’s forehead. Such blessings were not unusual and the prince needed all the protection he could get: on the one hand, his father’s peripatetic court moved endlessly across the country according to the emperor’s whims or necessity; on the other, the process of accession to the throne often broke out into contests and violence (the right of primogeniture was not firmly established and members of the extended royal family schemed and competed against each other). It was probably for the best that the young prince was sent to study at the monastery of Dabra Abbay, a complex situated on the northern bank of the Takkaze River, to the south-west of the modern town of Shire. In medieval Ethiopia, as in Europe, monasteries were repositories of knowledge and centres of learning, and, judging from the many theological works which would later be written by Zar’a Ya‘eqob, the prince must have been a particularly gifted student. The Dabra Abbay monastery has preserved a remarkable collection of early manuscripts, some of which were probably seen by the prince, since they date approximately to the period in which he was sent there. One such manuscript, a Book of Hours, is illustrated with an image of the Virgin and Child and a set of colourful portraits of the apostles holding scrolls. The miniatures in this manuscript, which are strikingly hieratic and highly stylised in character, function as pictorial frontispieces marking the beginning of each new textual section.

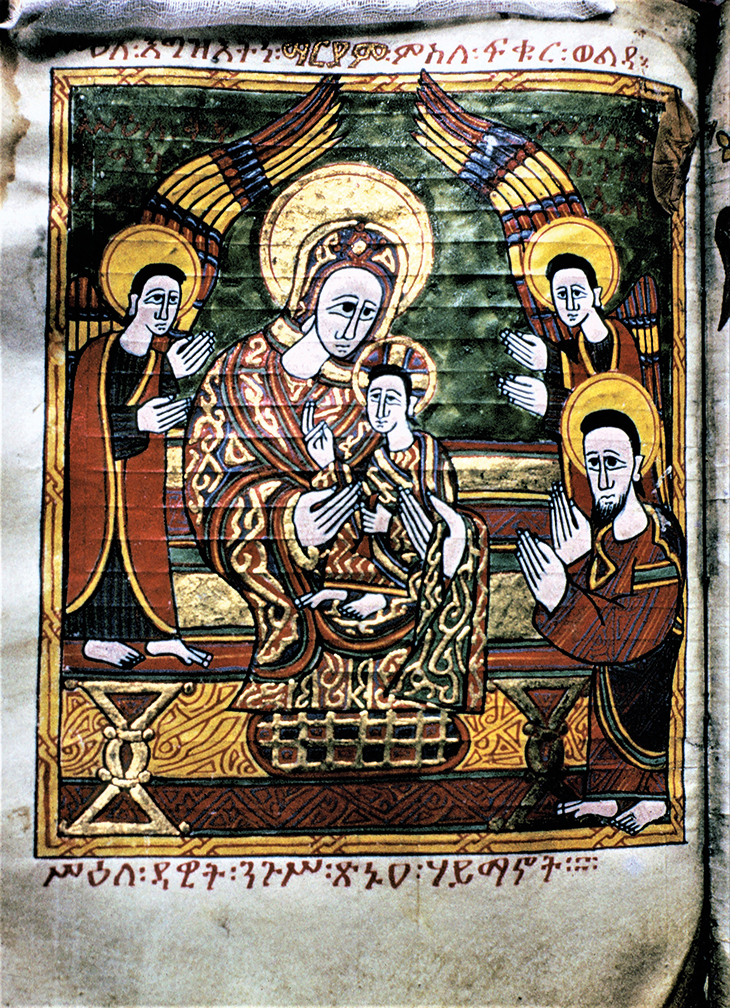

In 1413 Dawit II died after being kicked by a horse. After Zar’a Ya‘eqob’s half-brother Tewodros I was crowned emperor, the prince, who would have been about 14 years old, was imprisoned with other relatives on Amba Geshan, an almost inaccessible 3,000m-high amba – the Ethiopian name for a fortress-like flat-topped mountain – regarded as a place of particular significance because of its distinctive cross shape. It was customary to banish men with royal blood to this barren mountain to reduce the risk of succession struggles between possible heirs. Yet Zar’a Ya‘eqob’s memories of this place cannot have been all bad since, years later, he had a church dedicated to the Virgin Mary built on its summit, endowing it with valuable items including a precious relic of the True Cross. That church has not survived, but among the treasures preserved in the modern church that has taken its place is a precious illustrated manuscript, one of the few in Ethiopia to be decorated with gold, which features a series of depictions of Dawit II adoring the enthroned Virgin and Child. For Ethiopian Christians, the Virgin, as the dwelling place of God, personifies the Ark of the Covenant, so the outstretched wings of the archangels Michael and Gabriel in the Geshan Maryam miniature allude to the two cherubim placed at each end of the Ark according to biblical passages such as Exodus 25:18. It is worth noting that the painter of these miniatures used chrysography for embellishing the vestments of the Virgin and the Child but not for the emperor, to emphasise the latter’s humility before God. Tewodros I (r. 1413–14) was succeeded by Yeshaq I (r. 1414–29), another half-brother, who was in turn succeeded by one of his sons, and so on. History has not preserved the particulars of what passed during Zar’a Ya‘eqob’s long period of captivity. In 1434, when the prince was in his thirties, he was freed (under what circumstances is unclear) and made emperor. The instability of the political situation is demonstrated by the fact that four kings had succeeded to the throne in the four years before his appointment. Among those who plotted against the new emperor were his daughter Shih Mangasa and her husband Isayeyyas. According to a group of homilies attributed to Zar’a Ya‘eqob that are known by the title Epistle of Humanity, his daughter and son-in-law consulted sorcerers and magicians to learn whether the emperor’s reign would be favourable to their interests. Upon learning that it would not, they conspired to overthrow him, but were discovered, put on trial and sentenced to severe punishments.

Emperor Dawit II in adoration before the Virgin and Child (late 14th–early 15th century), unknown artist, Ethiopia. Photo: courtesy the DEEDS project

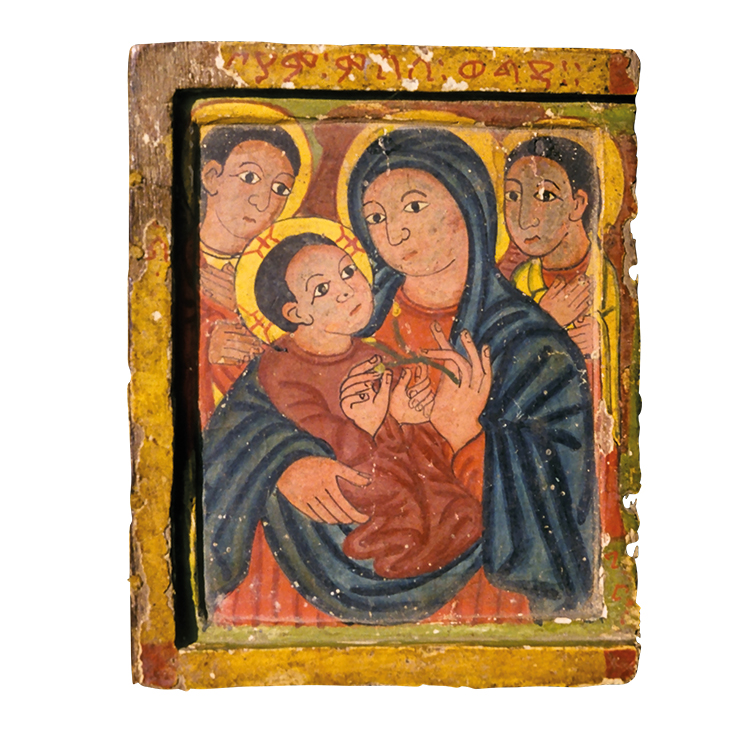

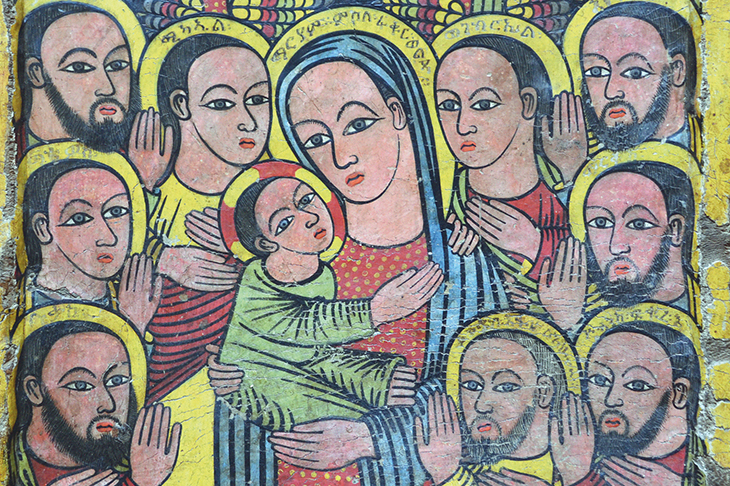

By the time of his coronation, which took place three years later, near Ethiopia’s holiest site – the Church of St Mary of Zion in Aksum, where tradition holds that the Ark of the Covenant is kept – his grasp on power was firm. He ruled until 1468 while waging a successful war against the neighbouring sultanate of Ifat and imposing a series of religious reforms designed to reconcile the different religious factions in his empire. Zar’a Ya‘eqob wrote theological treatises, particularly encouraging worship of the Virgin, introduced more than 30 feasts in her honour, and demanded that his subjects prostrate themselves before her image. In the mid 15th century there was a surge in the production of icons – which typically show the Virgin and Child surrounded by angels and Apostles or flanked by saints on horseback – that is undoubtedly connected to the emperor’s instructions. One of the most exquisite examples of the period would have thus originally been placed on an altar or throne in church. The painting’s linear elegance and clarity, together with the serene, contemplative expressions of its figures, would have instilled a sense of spiritual joy in those who beheld it. It also had a didactic function, for it shows the Apostles venerating the Virgin Mary and her Child. In other words, they perform, and therefore validate, the same act of devotion demanded from the viewers.

The emperor was a gifted politician and theologian, but callous in his treatment of opponents. When a group of monks, known as Stephanites after their leader, argued that the emperor’s devotion to Mary was excessive, they were persecuted and eventually put to death. In his writings, the emperor describes them as heretics, dubbing them as ‘enemies of Mary’ for refusing to prostrate themselves before her image, though he was probably more irked by their refusal to bow before him or recognise his authority in spiritual matters. Enraged by such defiance, Zar’a Ya‘eqob had Stephen bound, stripped of his monastic garb, and flogged. He was then shackled and thrown into a prison where he eventually died for the hardships he had to endure.

The Virgin and Child flanked by two holy men (late 15th or 16th century). Biblioteca Giovardiana, Veroli. Photo: Biblioteca Giovardiana

Even after Stephen’s death, his many followers did not escape Zar’a Ya‘eqob’s wrath, for they continued to refuse to bow before him, stating that ‘we do not prostrate ourselves before any other than the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit’. In some cases, the emperor had their noses cut off; in others, he had them flogged ‘until their blood flowed on the ground like water’. The Stephanites somehow managed to survive by settling in remote parts of the empire, where they built monasteries, wrote down the stories of their spiritual fathers and portrayed them in their own distinctive style of painting. In one such manuscript, we find a portrait of a monk called Ezra, who was sent with some of his brothers to Jerusalem to be ordained as a deacon, for the Ethiopian patriarch refused to do so. After an arduous journey, Ezra managed to reach Jerusalem, where he was consecrated by the Armenian Patriarch Hovhannes Missirtzee. Upon returning to Ethiopia he too faced persecution, but nothing of the suffering endured by these monks can be detected in this or any other painting, in which they appear to accept their martyrdom peacefully.

Zar’a Ya‘eqob was also determined to root out pagan and magical practices from his empire. He regarded sorcerers as a personal threat and fearing that they might harm him, he had priests sprinkle holy water on his tent every day and recite passages from the Gospels and Psalms from dusk till dawn for protection. In The Book of Light, an apologetic and disciplinary work, he condemns the use of oracles, accusing heretics and magicians of ‘turning astrology, idolatry, and magic’ into their God, and of ‘ridiculing the Old Testament and the Gospels’ for their ignorance of the science of the Holy Scriptures. What emerges from these and other works is the picture of a man deeply concerned about the religious practices of his subjects and the unity of his church, who was prepared to resort to violence to uphold what he considered as ‘orthodox’. No other Ethiopian sovereign had, or would later feel, the need to write down and justify his deeds and orders as much as Zar’a Ya‘eqob, who perhaps used writing to address his own conscience as much as his subjects.

Saint Ezra holding a hand cross and an open book (late 15th or early 16th century), unknown artist. Gunda Gunde monastery, Tigray. Photo: Michael Gervers

As part of his efforts to eradicate paganism and magical practices, Zar’a Ya‘eqob decreed that his people should have a cross tattooed on their hands or forehead – a practice which continues to this day in some parts of the country. He may have also encouraged his retainers to use small portable icons rather than magical charms for protection. When moving into battle against his enemies Zar’a Ya‘eqob is said to have worn an image of the Virgin Mary around his neck. This probably resembled the painting on the left wing from a small diptych preserved in the Institute of Ethiopian Studies in Addis Ababa, roughly dating to the time of his reign. The earliest examples of these icons belong to the mid 15th century approximately, and it seems likely that the emperor endorsed and promoted their production. Some portable icons have a pierced wooden cylinder at the top, through which a cord can be passed to enable the owner to hang it around his or her neck. Others, like the one shown here, would have been placed in a small leather satchel that could be worn by the owner, similar to the ones which to this day are used to protect manuscripts. Portable icons from this period, like the larger panels which the emperor’s subjects had to venerate in church, nearly always feature images of the Virgin and Child. In some examples, the Virgin holds a branch with buds. This motif, which may have been inspired by an Italian print or painting taken to Ethiopia as a result of the embassies exchanged between Zar’a Ya‘eqob and several courts of Europe, was probably understood as an allusion to Mary’s virginity, to the tree of Jesse in the Book of Isaiah (11:1), and the prophecy that ‘a bud shall blossom’ (Isaiah 27:6).

In 1445 Zar’a Ya‘eqob came face to face with his most dangerous opponent, Ahmad Badlay, the sultan of ‘Adal, who had already won several victories against the Christian forces of Ethiopia. On the eve of battle, according to a tradition preserved in the same manuscript in the Giovardiana Library that records his birth, men came to the emperor to offer him protective talismans made of wood or parchment scrolls with magic names. Zar’a Ya‘eqob ignored such suggestions and rode into battle wearing an image of the Virgin around his neck. When he met Ahmad Badlay, he slew him with his spear. The sultan’s body was cut into pieces and the war booty was donated to a church called the Mount of Thunder, founded by Zar’a Ya‘eqob a few years before. Here he had the bodies of his parents buried. And here he too would be buried after his death in 1468, having left an indelible mark on the socio-political and religious life of the Ethiopian empire.

Portable icon showing the Virgin and Child (mid 15th century), Master of the Round Faces. Institute of Ethiopian Studies, Addis Ababa. Photo: Stanislaw Chojnacki

From the November 2019 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home