Beside each one of Eugenio Dittborn’s large ‘Airmail Paintings’, currently at Goldsmiths Centre for Contemporary Art, is an envelope – or multiple envelopes, in some cases – on which the name, date and dimensions of the piece, a mailing address, an exhibition history or ‘itinerary’ and some lines of text about the work are handwritten. These are evidence of the artist’s long-running practice of mailing folded-up artworks from his home in Santiago de Chile to galleries across the world.

Dittborn has been making and sending these ‘Airmail Paintings’ since 1983, a decade into Augusto Pinochet’s brutal and insular regime in Chile. Though there are obvious similarities in terms of method, he was not involved in Ray Johnson’s New York Correspondence School (he has since paid homage to that project in the title of a work from 2012). Rather, Dittborn realised that by making a fold in a work it could be reduced in size and sent in the mail, a method allowing him to circumvent both the strictures of the regime in Chile and the difficulties of exhibiting internationally at that time. (Dittborn has said that he ‘invented these folded paintings to get out from this place, to be in the world.’) Fashioned from modest and lightweight materials – Kraft paper to start with and later fabric – the works are inscribed with the grid of folds from every instance of their mailing and unveiling.

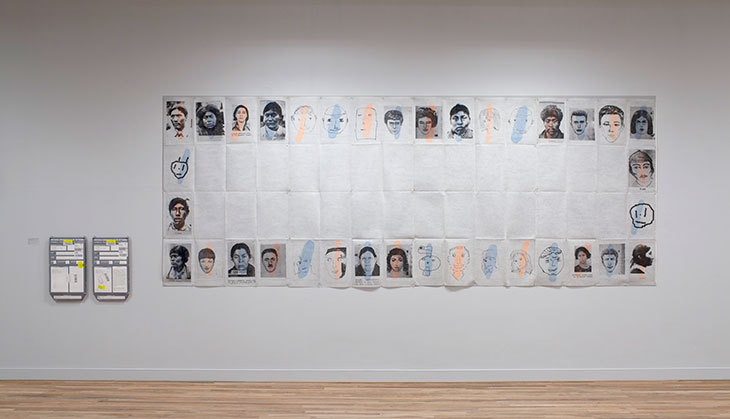

The 18th History of the Human Face (Eyes of Glory) Airmail Painting No. 109 (1993), Eugenio Dittborn. Photo: Bill Orcutt; courtesy Alexander and Bonin, New York

Each painting can be seen as a dispatch as much as an artwork, a reminder of the existence of the artist working in a cut-off society in the Southern hemisphere. Together, they cover several decades and show a number of repeated motifs, several relating to South American history and how information about the continent was brought back to Europe by translators and colonisers. An image of a severed head, from a reproduction of a historic Flemish engraving imagining cannibalism in South America, appears in two different works, as does a portrait of Jemmy Button, who was taken from his home in Tierra del Fuego to Europe in 1830 (he was renamed after the mother-of-pearl button for which he was ‘traded’). Photos of other Indigenous people from Tierra del Fuego appear alongside mugshots, self-portraits by psychiatric patients and faces drawn by the artist’s daughter in The 18th History of the Human Face (Eyes of Glory) Airmail Painting No. 109 from 1993. Labelled only with their first names, the faces of the Selk’nam people – who were almost entirely eradicated by colonisers – are both subject to and yet somehow also manage to evade ethnographic observation, a few not quite looking directly at the camera.

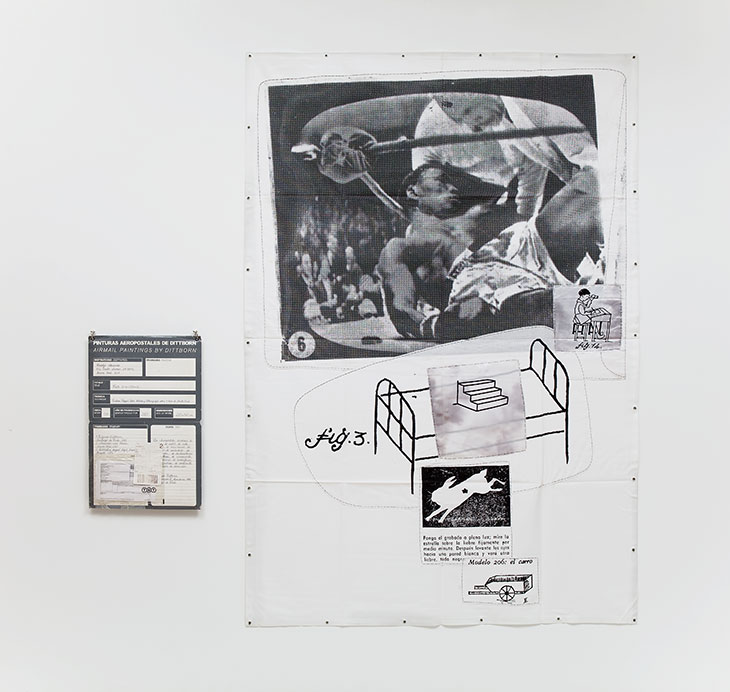

Images appear as fragments stitched, printed or pasted on to the fabric grids, accompanied by text and paint markings. The three video works on display, playing on a loop on a TV and similarly composed of fragments of footage, echo some of the imagery and ideas in the ‘Airmail Paintings’. A clip from a boxing match in La Historia de la Física (1982–2008) recalls the image of the boxer Benny Paret in Pieta (6+3+206+14), Airmail Painting No.139 (2001), who fell into a coma after a fight and subsequently died. His fate is echoed in another painting detailing the story of the artist’s sister, who also fell into a coma before dying. Though Dittborn’s method of exhibiting depends on starting and endpoints, geographically speaking, his work also emphasises in-between states such as prolonged unconsciousness.

Pieta (6+3+206), Airmail Painting No. 139 (2001), Eugenio Dittborn. Courtesy Alexander and Bonin, New York

In one six-panel fabric work titled To Return (YVR), Airmail Painting No. 102 (1993), the artist reproduces an image of the body of British sailor John Torrington, who died in 1846 and was buried on an island in the Arctic. Over a century later, in 1984, his body was exhumed, almost perfectly preserved, from the ice. Dittborn also includes the image of a mask that his sister had bought for him on a trip to Benin – she died on the return journey from malaria. Torrington was part of an expedition looking for a waterway, but there is a fine line between exploration and exploitation. The mask, though a gift from beyond the grave with a strong personal meaning, could also be read as a reference to the historic removal of cultural artefacts from West Africa, the most famous and vexed being the Benin Bronzes. And in the right-hand bottom panel, there again is the pensive face of Jemmy Button.

On one of the envelopes accompanying this work is a poem by the Chilean writer Gonzalo Millán. Titled ‘Dead Letter’, the poem refers to ‘a virus in action’. Though the work itself was made long before the Covid-19 crisis, looking at Dittborn’s work now comes with an increased awareness, perhaps, of what it means to communicate from a place of isolation or extremis. With Chile on the Red List for entry to England, Dittborn was unable to come to London to install the exhibition — a situation he, luckily, has plenty of experience navigating.

‘Eugenio Dittborn: Airmail Paintings’ is at Goldsmiths CCA, London, until 12 December.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home