In this ongoing series, Apollo previews a range of international exhibitions, asking curators to reveal their personal highlights and curatorial impulses. Catherine Lampert is the curator of ‘Daumier (1808-1879): Visions of Paris’ at the Royal Academy of Arts, London.

Can you tell us a bit about the exhibition?

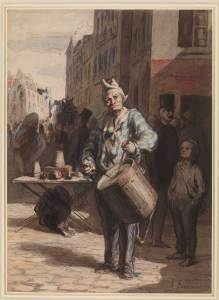

The exhibition covers all aspects of Daumier’s output, keeping in mind his great draughtsmanship, and the way his finely tuned visual memory captured with great immediacy what he saw around him. This is obvious in his lithographs but equally in the watercolours, paintings and sculpture on display. He frequently engaged with images of very ordinary moments and treated these without sentimentality or cynicism. He also brought to life enduring subjects, like crowd behaviour and the plight of fugitives from war and poverty.

What makes this a distinctive show?

Just as he satirised contemporary society and politics, Daumier was able to grasp the challenges artists were facing at the time, and have done so ever since – in particular the way the general public, along with critics and collectors, would come to dominate and sometimes trivialise opinion and patronage. This is a sub-theme of the exhibition. The exhibition’s leitmotif is the constant presence of art, sometimes indicated by the shadowy paintings and sculpture hanging in the background of so many of Daumier’s works. Daumier often left areas of the rectangle undefined, suggesting what couldn’t easily be put into words and was better expressed by ambiguity and, later on, a loose handling of the medium.

How did you come to curate this exhibition?

I have been thinking about a Daumier exhibition since 1997 when I was at the Whitechapel, and five years ago approached the Royal Academy. The intention was always to avoid rote themes (lawyers, transport…) and emphasise the artist’s empathy for people and his fascination with the act of looking. Thus, within a ‘critical judgement’ section, we have scenes of interrogation and the courtroom followed by connoisseurs regarding art and visitors to the Salon nosily voicing their opinions. The RA welcomed an unconventional approach.

What is likely to be the highlight of the exhibition?

Ecce Homo from the Folkwang Museum in Essen.

And what’s been the most exciting personal discovery for you?

The opportunity to examine the works under the conservator’s special lamps revealed amazing details like a little figure above the bugler in A Sideshow (c. 1860–64), or dashes of luscious green paint on the portfolios in the scenes of the ‘print collectors’. As Michael Pantazzi and Edouard Papet write in the catalogue, he turns out to incorporate complex and topical references to works he saw hanging in the Louvre, or sculpture he admired.

Man on a Rope (c. 1858), Honoré Daumier, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Tompkins Collection – Arthur Gordon Tompkins Fund

What’s the greatest challenge you’ve faced in preparing this exhibition?

Doing justice to Daumier. He was an astonishing caricaturist and lived in a period of revolution and social transformation: however, this reputation can blind admirers. His understated, introspective nature is allied with the subjects he cared most about: sometimes overtly tender and sensual encounters, sometimes animated conversations between friends eating and drinking together – modest subjects unlike those that attracted his contemporaries. I am hoping viewers will appreciate the authenticity and modernity of his art and see how far it went beyond the frameworks of romanticism, realism and even impressionism that dominate discussions of 19-century French art.

How are you using the gallery space? What challenges will the hang/installation pose?

Space in the Sackler Galleries is restricted – I would have preferred more – and, since we wanted to mix works on paper with paintings, the light levels have to be fairly low. The designer, Robin Kiang, has worked with the curatorial team to insure that the setting is restrained; we’ve clustered lithographs and tried to create plenty of breathing room.

Which other works would you have liked to have included?

A few ‘lost’ drawings from the Roger Marx collection known by photographs in the Witt Library and the catalogue raisonné. It wouldn’t be true to Daumier to look only for the masterpieces (all but a handful of these are in the exhibition).

‘Daumier (1808-1879): Visions of Paris’ is at the Royal Academy of Arts from 26 October 2013—26 January 2014.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home