Anne Lyden, the curator of ‘A Royal Passion: Queen Victoria and Photography’ at the Getty Center, tells us a little more about the exhibition, and the challenges of putting it together

Click here for a selection of photographs from the exhibition

Can you tell us a bit about the exhibition?

This exhibition explores the relationship between the new art of photography and the young Queen Victoria, whose passion for collecting photographs began in the 1840s and whose photographic image became synonymous with an entire age.

What makes this a distinctive show?

It is distinctive for placing the queen’s collection within a larger historical context of 19th-century photography and simultaneously charting her image, from early daguerreotypes and cartes de visite, to the official imperial portraits of the 1890s. She is shown first as loving mother, devoted wife, widow, and finally sovereign whose empire stretched around the world.

How did you come to curate this exhibition?

2014 is the 175th anniversary of the announcement of photography. I was interested in celebrating this particular moment in the history of photography by considering it from a slightly different viewpoint: that of the young Queen Victoria, who ascended to the throne in 1837. This exhibition was an opportunity to consider the overlapping histories of the young monarch (who was not yet 20 when the announcement was made in Paris and London) and the new medium.

What is likely to be the highlight of the exhibition?

I think a definite highlight of the show is the generous number of loans from the Royal Collection that are placed within the context of 19th-century photography, largely drawn from the Getty’s rich holdings in this area. It allows the visitor to better understand what Victoria was interested in with regard to photography, what she was viewing at the various exhibitions, and what she ultimately collected.

Also, the visitor has the opportunity to compare Victoria’s photographic portraits to those of non-royal subjects, which during the 1860s were remarkably similar in style and approach – one is able to see the democratising impact of the medium.

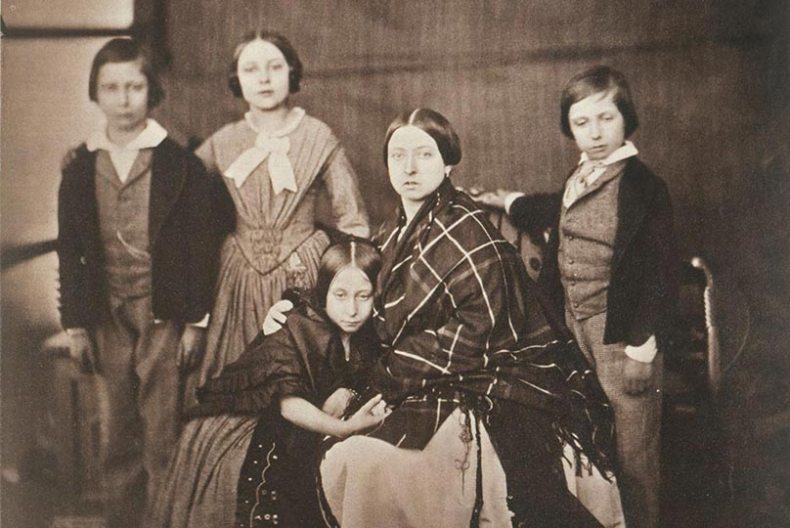

The Prince of Wales, the Princess Royal, Princess Alice, the Queen, Prince Alfred (negative February 8, 1854; print later), Roger Fenton © Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2013

And what’s been the most exciting personal discovery for you?

One of the most exciting discoveries for me was reuniting two rare daguerreotypes of the queen by Kilburn. One is from the Royal Collection and the other from a private collection in the US. Both images feature Victoria with five of her children (she bore nine in total) and were made just days apart in January of 1852. However, the queen did not like her appearance in the first daguerreotype and scratched the glass to obliterate her face. It would appear that Victoria, perhaps still unaccustomed to the relatively new medium, had inadvertently closed her eyes!

However, undaunted, she repeats the process two days later and has Kilburn create a second daguerreotype whereupon all the sitters compose themselves once more, but this time the queen elects to sit in profile and dons a wide-brimmed bonnet to prevent any further ungainly poses. To be able to demonstrate Victoria’s relationship to photography with these two special objects, that have not been together in over 100 years, is really quite special.

What’s the greatest challenge you’ve faced in preparing this exhibition?

The greatest challenge I’ve faced in preparing this exhibition is the fact that Victoria lived and ruled for such a long time. She was queen from 1837 to 1901 – effectively the entire 19th century for photography. The constant evolution of the medium, its uses and applications together with the history of the monarch during this lengthy period is enough content for tenfold exhibitions and publications. Selecting and editing the objects for just one large display was incredibly thrilling, but quite hard at times.

How are you using the gallery space? What challenges will the hang/installation pose?

The photographs galleries at the Getty are among the finest display spaces in the world and we are certainly making great use of their volume with this exhibition! The display features over 170 objects that are spread throughout five galleries, each one focusing on a particular theme or period: the beginnings of photography and Queen Victoria’s rule; the photographic exhibitions of the 1850s; the rise and evolution of photography in the 1850s; art and war; and the queen’s portrayal through the centuries.

Due to the range of objects include in the exhibition, there are several challenges for the installation and it takes a team of conservators, exhibition designers, art handlers, and mount makers to get everything safely installed. For example, we are featuring a souvenir brochure of the queen’s coronation parade in 1838 that measures 20 feet in length! I think our visitors will really enjoy seeing the publication extended its full length.

Also, through the generosity of the National Media Museum in Bradford, England, we are displaying two original calotype negatives by William Henry Fox Talbot that are illuminated from behind so visitors can see the image in detail. We also have a number of stereographs, one of which features the queen, that are mounted within stereoviewers so visitors can view the images in 3D, as they were intended to be seen in the 1850s.

Which other works you would have liked to have included?

With over 170 objects it is difficult to imagine that one would wish to include more, but at one point we had hoped to include two painted miniatures of Victoria and Albert upon the occasion of their engagement in 1839.

These small paintings were created at a time when photography was so nascent it was not yet able to successfully record a portrait. These small objects relate to the later daguerreotypes of the royal family and are, in a way, symbolic of this transitional moment in portraiture. However, the works themselves are so delightful and in demand, they were already committed to another exhibition at Kensington Palace, London.

‘A Royal Passion: Queen Victoria and Photography’ at the Getty Center, Los Angeles, from 4 February–8 June 2014.

Click here for a selection of photographs from the exhibition

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home