What is art? That perennial question that dogs the art world never quite seems to have an answer. Grayson Perry tried to tackle it in his Reith Lectures last year, and one of his suggestions was that art is what is in an art museum. So then the question becomes even more interesting: what does it mean to put something in an art museum?

dock (2014), Phyllida Barlow. Photo: J Fernandes, Tate Photography

These two questions together – object and context – seem to me to have been at the centre of this season’s selection of displays at Tate Britain. On one side of the Duveen Galleries you had ‘British Folk Art’ – an exhibition of objects brought together under an ‘elusive, contradictory and contested term’ but self-consciously not those usually seen in a national art museum. On the other, ‘Kenneth Clark: Looking for Civilisation’ considered the role of one man’s taste, collecting and influence in defining the British art world, its canon and its institutions in the last century. Between these two, Phyllida Barlow’s monumental commission fills the Duveen Galleries with an installation made from unassuming everyday materials.

There is an interesting line to be traced between these three displays. One of the elements that distinguishes folk art might be its connection with everyday materials and practices; one of Clark’s long-running concerns was about the relevance of abstract art to everyday experience. One of the last rooms of ‘British Folk Art’ brings together objects and textiles with a ‘purely abstract character’ divorced from their function to give them a different interest within the art museum. Barlow’s installation brings these contrasts nicely together.

A running theme of ‘Looking for Civilisation’ is, likewise, Clark’s role in discovering and supporting certain artists – Henry Moore, Graham Sutherland, John Piper, Sidney Nolan – while the exceptions within the makers featured in ‘British Folk Art’ are Alfred Wallis and Walter Greaves. ‘Discovered’ and lauded by curators and artists, these men’s works have become staples of the modern art museum, and are purposefully made to resonate differently by the comparable works of their obscure fellows. It struck me that, in many ways, the most crucial case in the ‘Folk Art’exhibition was the final one, in the room of archive photos (barely glanced at by many visitors), which considered the publications responsible for the shaping of ideas of high art versus folk art and what is in or out of the canon. Men like Clark are, of course, key here.

A running theme of ‘Looking for Civilisation’ is, likewise, Clark’s role in discovering and supporting certain artists – Henry Moore, Graham Sutherland, John Piper, Sidney Nolan – while the exceptions within the makers featured in ‘British Folk Art’ are Alfred Wallis and Walter Greaves. ‘Discovered’ and lauded by curators and artists, these men’s works have become staples of the modern art museum, and are purposefully made to resonate differently by the comparable works of their obscure fellows. It struck me that, in many ways, the most crucial case in the ‘Folk Art’exhibition was the final one, in the room of archive photos (barely glanced at by many visitors), which considered the publications responsible for the shaping of ideas of high art versus folk art and what is in or out of the canon. Men like Clark are, of course, key here.

In both the exhibitions indeed, we saw a common feature of art and art museum display: contextual materials and photographs were relegated to separate cases and often the final rooms, the art works required to exert a pure aesthetic power of their own. I would have loved to see images within the displays of both the folk art and Clark’s collections used and combined in their original contexts. The choice of display style, so very different to a social history or ethnography museum, is surely one that characterises ‘art’: an object expected to convey meaning and emotion entirely on its own, without the explanatory material we would consider crucial to any other display. There was something both sad and powerful about these objects pulled from their contexts, made to act alone.

Yet, the overriding message that I took from these two contrasting shows was the breadth and richness of museum collections across the UK. Both ‘British Folk Art’ and ‘Kenneth Clark’ are distinctive for the wide range of collections from which objects have been borrowed – bringing folk art out of regional museums of which I had never heard, re-uniting a private collection which has spread across the globe. The fact that two such disparate exhibitions can be brought together at Tate in 2014, I think heralds a changing moment for what art and art museums will be in the coming years.

More comment from the Muse Room…

Related Articles

Review: ‘British Folk Art’ at Tate Britain (Danielle Thom)

Review: Kenneth Clark at Tate Britain (Peter Crack)

Disarmingly joyful: Phyllida Barlow’s ‘dock’ at Tate Britain (Lily Le Brun)

Looking Good: National Gallery exhibitions promote close looking (Rosalind McKever)

An English sculptor in England: Five works by Andrew Lord in the Tate (Lisa Zeiger)

Folk Art and ‘Civilisation’: the question of art in context

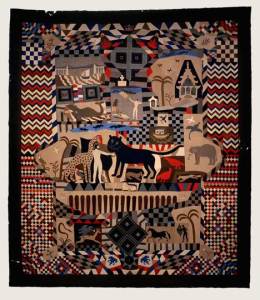

God in a Bottle (group) Artist unknown. Beamish Museum (Durham, UK), photograph by Marcus Leith & Andrew Dunkley/Tate Photography

Share

What is art? That perennial question that dogs the art world never quite seems to have an answer. Grayson Perry tried to tackle it in his Reith Lectures last year, and one of his suggestions was that art is what is in an art museum. So then the question becomes even more interesting: what does it mean to put something in an art museum?

dock (2014), Phyllida Barlow. Photo: J Fernandes, Tate Photography

These two questions together – object and context – seem to me to have been at the centre of this season’s selection of displays at Tate Britain. On one side of the Duveen Galleries you had ‘British Folk Art’ – an exhibition of objects brought together under an ‘elusive, contradictory and contested term’ but self-consciously not those usually seen in a national art museum. On the other, ‘Kenneth Clark: Looking for Civilisation’ considered the role of one man’s taste, collecting and influence in defining the British art world, its canon and its institutions in the last century. Between these two, Phyllida Barlow’s monumental commission fills the Duveen Galleries with an installation made from unassuming everyday materials.

There is an interesting line to be traced between these three displays. One of the elements that distinguishes folk art might be its connection with everyday materials and practices; one of Clark’s long-running concerns was about the relevance of abstract art to everyday experience. One of the last rooms of ‘British Folk Art’ brings together objects and textiles with a ‘purely abstract character’ divorced from their function to give them a different interest within the art museum. Barlow’s installation brings these contrasts nicely together.

In both the exhibitions indeed, we saw a common feature of art and art museum display: contextual materials and photographs were relegated to separate cases and often the final rooms, the art works required to exert a pure aesthetic power of their own. I would have loved to see images within the displays of both the folk art and Clark’s collections used and combined in their original contexts. The choice of display style, so very different to a social history or ethnography museum, is surely one that characterises ‘art’: an object expected to convey meaning and emotion entirely on its own, without the explanatory material we would consider crucial to any other display. There was something both sad and powerful about these objects pulled from their contexts, made to act alone.

Yet, the overriding message that I took from these two contrasting shows was the breadth and richness of museum collections across the UK. Both ‘British Folk Art’ and ‘Kenneth Clark’ are distinctive for the wide range of collections from which objects have been borrowed – bringing folk art out of regional museums of which I had never heard, re-uniting a private collection which has spread across the globe. The fact that two such disparate exhibitions can be brought together at Tate in 2014, I think heralds a changing moment for what art and art museums will be in the coming years.

More comment from the Muse Room…

Related Articles

Review: ‘British Folk Art’ at Tate Britain (Danielle Thom)

Review: Kenneth Clark at Tate Britain (Peter Crack)

Disarmingly joyful: Phyllida Barlow’s ‘dock’ at Tate Britain (Lily Le Brun)

Looking Good: National Gallery exhibitions promote close looking (Rosalind McKever)

An English sculptor in England: Five works by Andrew Lord in the Tate (Lisa Zeiger)

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

Share

Recommended for you

Gallery: Shigeru Ban designs the Aspen Art Museum

How does the new building compare to the architect’s previous projects?

Edinburgh Art Festival: what not to miss

Heading to Edinburgh? Here are six fine art exhibitions to visit while you’re out there…

First Look: ‘Discovering Tutankhamun’ at the Ashmolean Museum

The Ashmolean Museum will offer a new perspective on a famous archaeological find this summer