From the March 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

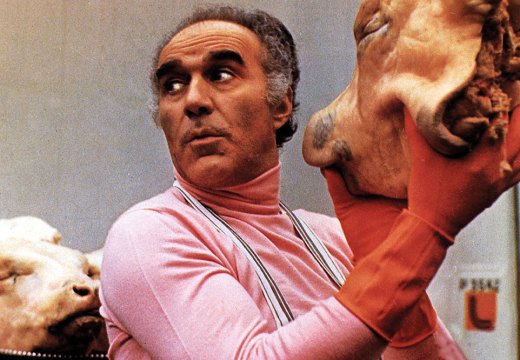

In March 1974, the painter Roger Hilton wrote a 22-page letter to Peter Townsend, the editor of Studio International. ‘Because I have peripheral neuritis I have largely lost the use of my legs, the arms & midriff are going,’ it began. ‘I have a skin condition which is driving me mad. All this is caused by alcohol. The usual vicious cirkle [sic]. You have to have more to cover up the pain which it creates.’

Illness had taken over Hilton’s life and practice. From October 1972, he existed almost entirely in a single, ground-floor room in the house in Botallack, Cornwall he shared with his wife, Rose Hilton – also a painter – and their two young sons, Fergus and Bo. These are the circumstances under which Roger Hilton produced the Night Letters, a collection of shopping lists, notes, drawings and gouaches. They came to be called Night Letters because that is what many of them were: rhetorical queries, disgruntled accusations and outlandish demands, directed at Rose and written, out of anger or desperation, while she slept. When Hilton was not preoccupied by his illness and the discomfort that it created, he was preoccupied by painting and drawing or food and drink.

‘It is the middle of the night. I can’t sleep & have no whisky left. 3.45. My God. 4 hours to go,’ is the opening to one. ‘You silly cow, you have taken everything I need … you never got me whisky + cigs. You took my teaspoon, soup spoon, all the coffee sugar milk,’ is another. ‘I had about 3 of the radishes … Why the devil didn’t you go ahead with braising the celery?’, ‘You pinched the more interesting of my two apples. Where is the other refill for my stove … Thanks for eggs. As you have eaten nearly all my walnuts perhaps you could get some more,’ and so on. The stove in question (on which he made coffee or spaghetti, or warmed milk) had once almost killed him, when it set his bedclothes alight. Hilton’s life, work and family were saved by the proximity of the local fire brigade, but some letters – adding to their food and coffee stains – were singed. A few burned completely.

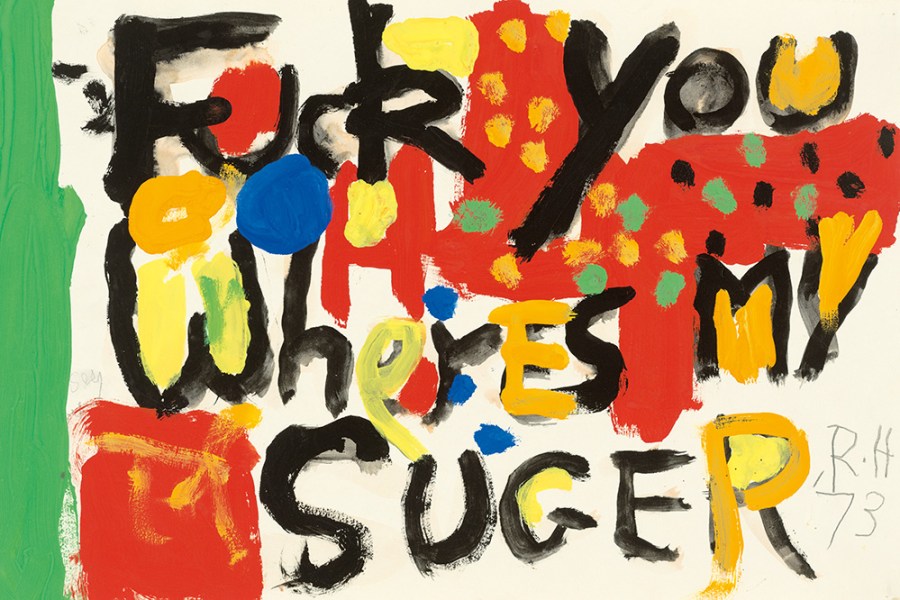

Hilton did not conform to the stereotype of the starving artist. He was hungry, and his art was an art of appetites. He once described paint as a ‘fleshy, lecherous and lurid’ medium. His work was lusty, lascivious and characteristically ravenous; breasts and genitals are everywhere, even in the abstracts. In the Night Letters, Hilton’s hunger takes on a more explicit, sometimes scopophilic, quality. One list asks for ‘Butter____Scotch’ (Hilton’s recurring shorthand for butter, whisky and sweets) and ‘more of that sausage’. The words share a page with a naked woman next to Hilton’s table, which has whisky bottles on top and a cat prowling beneath. In place of the woman’s face is an erect cock and balls.

This is the period where Hilton was confronted by his hungers and forced to reconcile them with his fantasies. In many of the lists his demands turn wild. He tells Rose, ‘you can get French bread in soho. Go up once a week + buy it. + Camembert. Let’s have some good grub around.’ Soho, as the crow flies, was 260 miles from the Hiltons’ home.

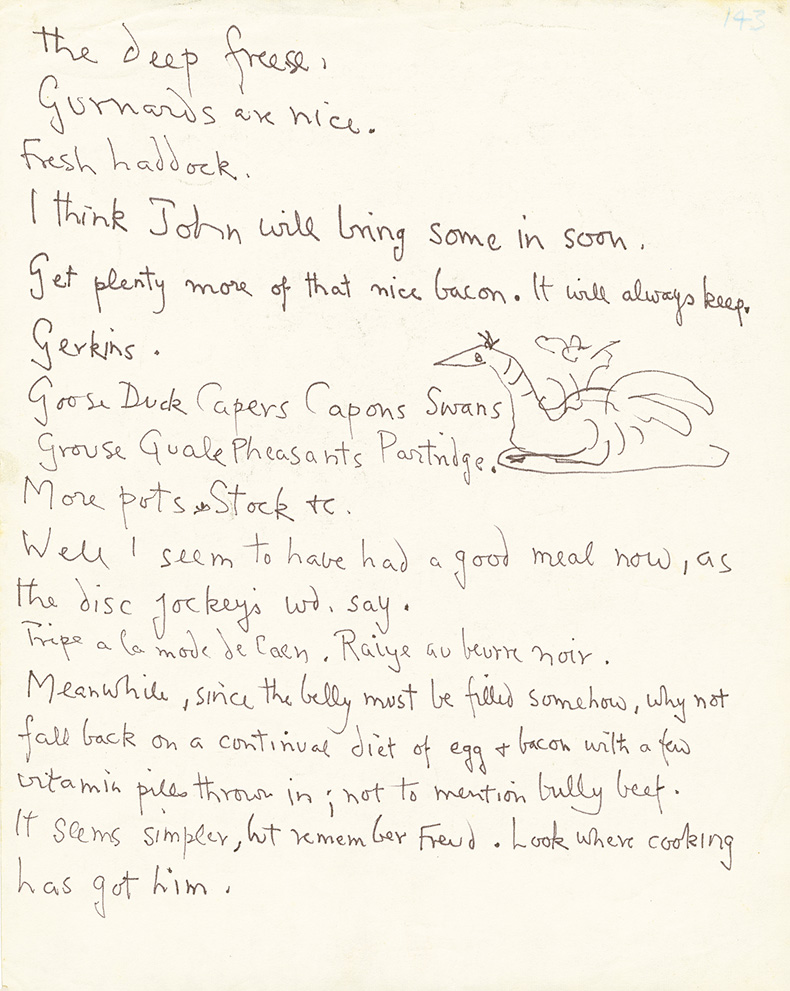

A page from Roger Hilton’s Night Letters (1974–75). © Estate of Roger Hilton

For Rose, the lists were geographically and financially unworkable. For Roger, the problems were physical. Alcohol had decimated his digestion and rich food was near impossible to eat. The purpose of the letters, then, was to express not only demands, but also desires. Items like ‘gherkins’ and the ubiquitous ‘refills for stove’ were followed by delicacies and daydreams, such as ‘Goose Duck Capers Capons Swans’, or ‘Grouse Duck Ptarmigan Liars Cheats Breakies Marmalade’. In one letter (headed by an illustration of Rose, breasts resting on her arm, sat at a table laid with jugs of wine and an enormous roast bird) he requests ‘Squid. Octopus. Whitebait’, which he follows with the consolation, ‘think nothing of it’.

There are around a thousand Night Letters in total, in which Hilton struggles through his illness, incapacitation and circumstance in pursuit of the delicious and of the divine. (‘Art, by and large, is in the mind,’ he said. It is ‘essentially a breaking out’.) For Hilton, it seems, the opposing pulls of practicality and purpose were irreconcilable. In one late letter he wrote, ‘the eating thing is idiotic; the fucking thing is equally idiotic; the song, music, Art thing is idiotic. What remains? Nature raw in tooth and claw.’ Like Tennyson, he was in mourning. Unlike Tennyson, he was in mourning for his self, his rotting tooth and yellowed claw. He was mourning a life he could sustain neither with nor without – the life of an angry and decaying person who lived, until his death, at the mercy of his appetite.

From the March 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home