From the June 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

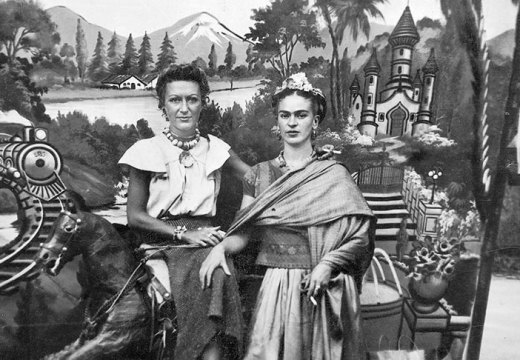

Frida Kahlo went to Paris in January 1939 at the invitation of André Breton, who wanted to put on an exhibition of her work and of Mexican work more generally. Kahlo wrote scathing and hilarious letters about Breton and the disorganisation and squalor of his household, which she partially blamed when almost immediately she became ill and had to be hospitalised. The situation was redeemed by the appearance of a warm and gracious American woman: Mary Reynolds.

Minnesota-born Reynolds had by then been living in Paris for some 18 years; she insisted Kahlo recover at the home she shared with Marcel Duchamp, full of friends (Jean Cocteau, Alexander Calder, Constantin Brancusi) and their works of art. Reynolds’s collection of earrings hung in pairs along the walls; Duchamp’s room was layered in road maps; and the garden’s marble Brancusi presided over nightly dinner parties. Thus began an entirely different stay for Frida Kahlo, one subject of this stellar exhibition, ‘Frida Kahlo’s Month in Paris: A Friendship with Mary Reynolds’.

Mary Reynolds was a private artist, who worked in the medium of book-binding, reliure, to create sculpture-books that extended the meanings of the books they contained with exquisite sensitivity, piercing wit, and materials now troubling (goatskin, toadskin, ostrich). Dozens of works by Reynolds, by far the most exhibited at an institution, are on view in Chicago. Curator Caitlin Haskell writes in the catalogue: ‘a binder of books, Reynolds was also a binder of community’. Seeing the work of Reynolds and Kahlo among that of their peers creates a new understanding of their work, and of Surrealism in a critical moment before the Second World War.

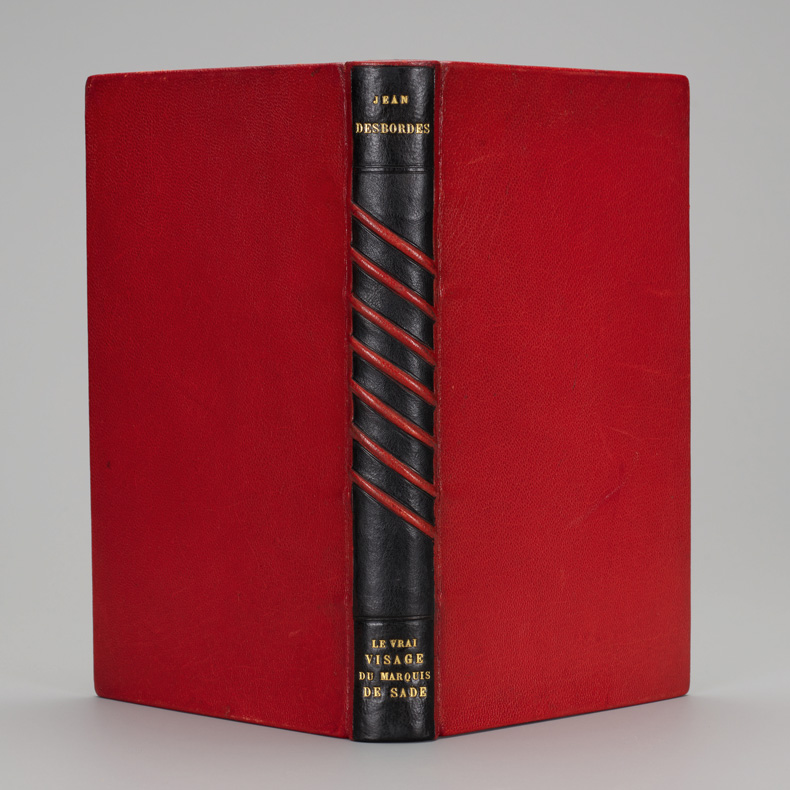

Le vrai visage du Marquis de Sade (The True Face of the Marquis de Sade) by Jean Desbordes, (1939–42/1945–50), Mary Reynolds. Art Institute of Chicago

Both the exhibition and the catalogue have been designed to suggest what germinated in that month’s visit. At each end of the museum show, there is a small room, and these are bound together by a long central gallery; the exhibition is itself book-ended by arrival and departure. In the first room we can see Kahlo (recently emerged from the shadow of her more famous husband Diego Rivera), already painting with the authority and textured clarity that impressed not only the Surrealists, but also French museums. In this room is The Frame (1938), Kahlo’s self-portrait on aluminum in an artisanal frame of painted glass, which was acquired for the Jeu de Paume. We also see Mary Reynolds, in photographs taken of her by Man Ray and in perhaps the best-known work she made herself, Les mains libres (free hands). This is a bound book in brown goatskin that has on its cover the witty overlay of a pair of brown leather gloves stitched on and flat, so that the gloves appear to be hands holding the book, at once free and bound. The pages within are a book of drawings by Man Ray with poems by Paul Éluard and the layers of collaboration, welcome and disparition embodied in those gloved and absent hands make the object a fitting emblem of the exhibition as a whole.

The meeting of Kahlo and Reynolds is a crucial knot in a net of Surrealist artists that includes Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo, Mina Loy, Gertrude Abercrombie, Lola Álvarez Bravo, perhaps even Lenore Tawney and Ruth Asawa. In the work of these artists, people, animals, plants, and even books and works of art have a living presence. Thin and cutting filaments do not break figures down into geometric objects; even when figures suffer, they are still seers.

The Wounded Deer (La venadita) (1946), Frida Kahlo. Private collection. Photo: © 2025 Bancó de Mexico Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museum Trust, Mexico, D.F./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

A view of a wider, more various Surrealism opens out in the long vitrined gallery at the Art Institute. I am not sure I have ever been in a clearer space of historical consideration. The vitrines are waist-high along counters that are austere invocations of shelves and of a central gathering table. Here is Reynolds’s thinking: a thermometer down the spine of Raymond Queneau’s Un rude hiver (A Hard Winter); blood-red slashes along that of Jean Desbordes’s The True Face of the Marquis de Sade; cosmic starry endpapers for Cocteau and Antoine de Saint-Exupéry; dappled leather and ferned insects for Duchamp and Éluard. In the context of these sharp lines and thin layers of vegetation and skin, The Wounded Deer (1946) – a small Kahlo painting in which a deer with the artist’s face is pierced with arrows – becomes less an iconic, isolated face, more a fantastic study of pain and paint. Here, too, are works by Brancusi, Calder, Joseph Cornell, Duchamp, Cocteau, Yves Tanguy and others; the dead seem to be calling to one another via their address books, letters, drawings with intimate dedications, small paintings, lofty sculptures, paper collages and borrowed patterns.

At the central table, people paused to page through copies of the show’s catalogue, itself an art object. Edited by Haskell with Tamar Kharatishvili and Alivé Piliado Santana, it includes Haskell’s wonderfully inventive essay ‘Frida Kahlo and Mary Reynolds: A Surrealist Drama in Five Acts’, followed by a theatrical ‘cast of characters’, and the pages for the exhibition objects laid out with feeling exactitude across the pages: a book (which can travel) inside an exhibition (which won’t) about how books may hold the meaning of artistic movements.

The exhibition’s last room, of departures, tells of the eventual show, ‘Mexique’, and of how Kahlo’s work made more than one lasting mark. Many of the Surrealists would follow her to Mexico, where she and Rivera helped them to get papers and places to stay. At the centre of this room is an edition of Duchamp’s Box in a Valise, the suitcase ready for flight, containing his works in miniatures Mary Reynolds helped fashion. Reynolds’s escape from France in 1942 became the stuff of legend, but her sculpture-books already understood a great deal about flight, cruelty and incisive lines. On the last wall is the drawing Duchamp created as the bookplate for the Reynolds collection that, after her death in 1950, found its home at the Art Institute of Chicago. His line drawing of her profile looks like a Cocteau, with bold earrings fashioned out of her twined initials: M R.

‘Frida Kahlo’s Month in Paris: A Friendship with Mary Reynolds’ is at the Art Institute of Chicago until 13 July.

From the June 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Apollo at 100