From the April 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

In 1887, four years before his erstwhile protégé departed for Tahiti for the first time, Camille Pissarro confided gossip about Paul Gauguin’s newest artistic persona as a ceramicist to his son: ‘This was the art of a sailor, a bit taken from everywhere.’ Pissarro’s description was apt. Borrowing, recombination, transposition and appropriation remained the modes of Gauguin’s artistic practice throughout his life. Yet if Pissarro found little to redeem the syncretism of Gauguin’s work as he departed further from his mentor’s Impressionism, Nicholas Thomas’s concerted aim in his new book is to show that there is value in the difficulty of pinning down Gauguin.

This difficulty arises in part from the fact that Gauguin did so many different things in so many different places. Born in France but raised partly in Peru, he began working life as a sailor in the merchant marine and then the French Navy. He remained in seemingly constant movement throughout his artistic career, assembling personal obsessions and stylistic signatures as he jittered to and fro across Europe, to Central America and the Caribbean, and then to the Pacific Islands where he lived off and on until his death. The sense we get in this book, as we move from the Impressionism of early paintings such as Working the Land (1873), with its open debt to Pissarro’s Le Printemps (1872), to the plaintive uncertainty of his monumental late work D’où venons-nous? Que sommes-nous? Où allons-nous? (1897–8), is of an artist with a restless appetite for experimentation and reinvention. As Thomas puts it, Gauguin’s ‘very inconsistency was characteristic’.

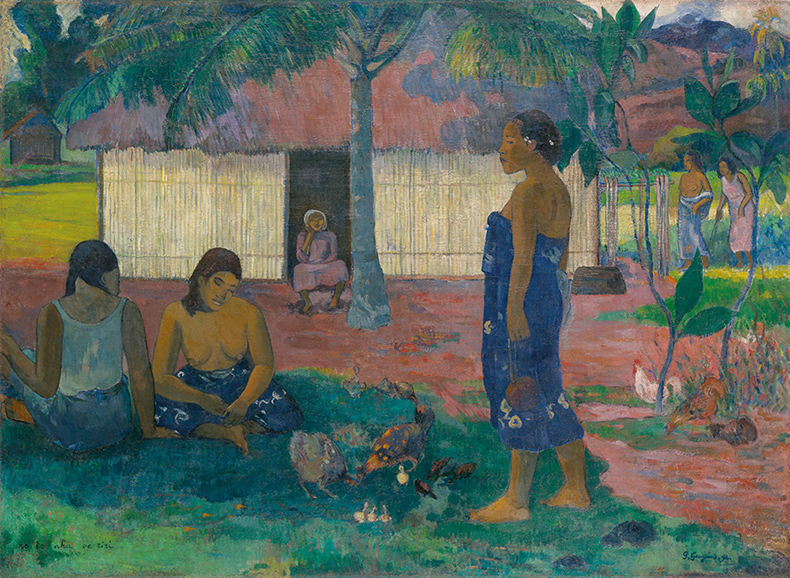

No te aha oe riri (Why Are You Angry?) (1896), Paul Gauguin. Art Institute of Chicago

At the culmination of an academic career at the intersection of Pacific and European art, Thomas is well equipped to lead readers through the geographic and stylistic contortions of Gauguin’s work – an endeavour he often undertakes through trenchant repudiations of Gauguin’s many previous critics. These are at their most effective when unpicking prior assumptions and misunderstandings. Thomas brings, for instance, an impressive knowledge of the significance of textiles in Tahitian culture to his readings of Gauguin’s art. Previous commentators have expressed disgust at the white cotton dresses worn by Gauguin’s Tahitian subjects (Abigail Solomon-Godeau calls them ‘hideous muumuus’), which they see as symbolising the cultural erasure and disempowerment of Pacific women.

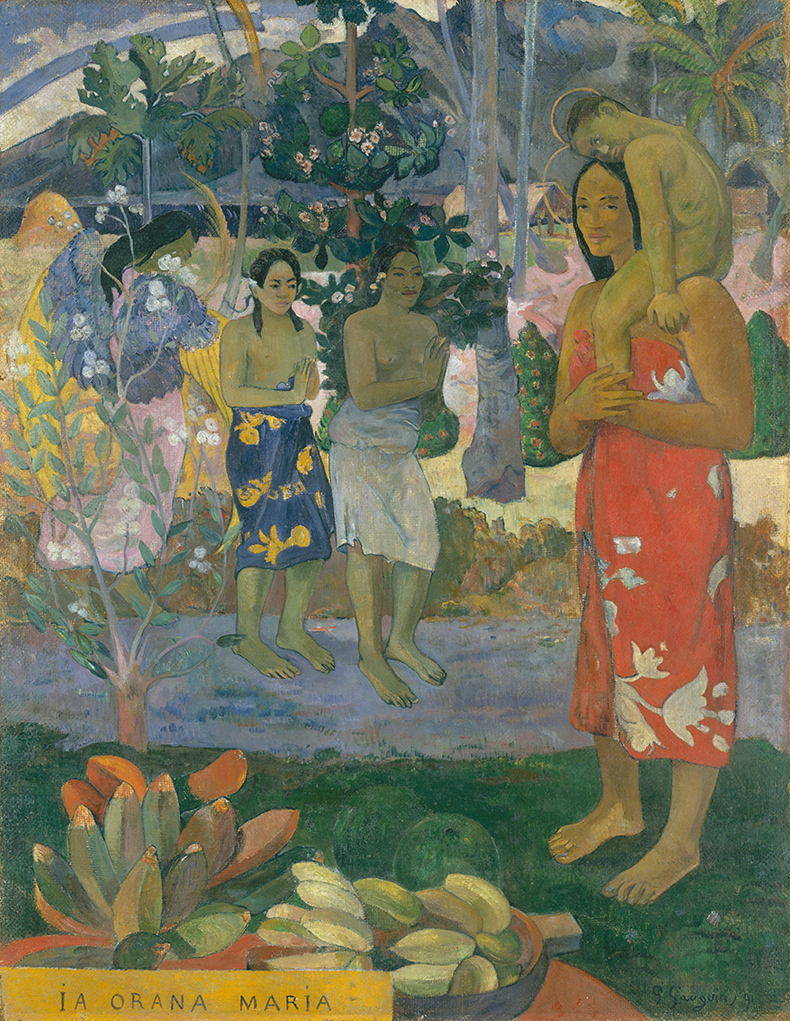

Ia Orana Maria (Hail Mary) (1891), Paul Gauguin. Metropolitan Museum, New York

By contrast, Thomas argues that cloth marked prestige, wealth and tapu or sacredness in Tahitian culture, so that these clothes in their elaborate voluminousness can be viewed as signs of self-assertion and power instead of subjection. Indeed, as Thomas points out, to ignore the ways in which Pacific women themselves appropriated and reconfigured European conventions of dress and self-expression risks robbing them of agency even while claiming to do the opposite. Thus, Thomas urges, while Gauguin has been notorious for his nudes, his faithful depiction of Tahitian costume should be acknowledged. Indeed, there are only seven extant nudes from the first period of his residence in Tahiti as compared to more than fifty of women dressed in pareu or robes. Thomas uses such facts to argue that Gauguin’s pictures offer an unparalleled vision of Polynesian culture as resilient and adaptive.

At times, appreciating Gauguin on these grounds involves significant forms of selectivity and interpretation on Thomas’s part. Thomas’s antagonists here include not just prior art historians, but Gauguin himself, whose racist and sexist accounts of his life and work need repeatedly to be set aside as naive or untrue to the work, or even as intentionally misleading: ‘This artist, even more than most, laid false trails prolifically and energetically.’ Indeed, Thomas’s enthusiasm for Gauguin occasionally carries this tendency too far. It is not clear to me, for example, why an argument for Gauguin’s skill as a documenter of Polynesian life requires a defence of his sexual relationships with very young Tahitian women.

Assertion of the commonplace nature of such behaviour cannot exonerate it – even if Gauguin’s own tone didn’t make it clear just how outlandish he found his situation to be: ‘I have a fifteen-year-old wife who cooks my grub and gives me a great blow job, whenever I want, all for the reward of a frock, worth ten francs, a month.’ Nor is it convincing to claim that such relationships operated in ‘a realm of accommodation and give-and-take, not so different from both heterosexual and same-sex relationships in many other places and times, always inflected by differences in age and wealth’.

Three Tahitian Women (1896), Paul Gauguin. Metropolitan Museum, New York

It is possible to the find the artist’s lingering gaze in Mana’o tupapau (1892) uncomfortable, while still comprehending the power of the returned gaze in Nevermore (1897) or the authoritative ease of Te Arii Vahine (1896). As Thomas notes, Gauguin is uneven and perhaps unsystematisable in his output. But at times it feels though the reader is asked to judge him and his work together, as either uniformly innocent or guilty.

At other times, however, Thomas convincingly preserves subtlety. As he writes, ‘Yes: [Gauguin] claimed to be preoccupied with the vanishing, remote and mysterious past, and saddened by its displacement by modernity. Yet his work did something different, something quite other than romantic or nostalgic ethnography. He invented and reinvented, but also responded to what was there.’ At its best, then, Thomas offers a nuanced version of Gauguin’s works as at once obviously open to influence and highly attentive to the particulars of the Polynesian world. Indeed, his aesthetic dedication to synthesis seems to permit the distinctive attention he pays the Polynesian world. Thomas draws out how Polynesian life remade European influence. In this view, far from being markers of wilful ‘incomprehensibility’ or ‘mystery’, Gauguin’s eclecticism and syncretism are the tools he uses to apprehend and document – the ways in which he sees ‘what was there’.

Matthew Kerr is a lecturer at the University of Southampton.

From the April 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home