The influence of Scandinavian design on modern British interiors has been so marked, and so enduring, that it takes a leap of the imagination to appreciate that there was a time when Nordic countries suffered a sense of inferiority in the applied and decorative arts. This sense, and an associated urge to develop a national style, was particularly acute in Norway just prior to its secession from Sweden in 1905. The Norwegian artist and designer Gerhard Munthe (1849–1929) played a key role in this cultural journey. As Jan Kokkin remarks, Munthe was ‘dismayed by the massive importation of handicrafts’; he complained that ‘all the things we have in our houses belong to foreign ideas and foreign invention, thus making us homeless in our own living rooms.’ His answer was not to champion the ‘Dragon style’ – a popular and exportable interpretation of shared Viking heritage – but to develop a more specifically Norwegian vision, inspired by peasant rosemaling (rose painting), fairy tales, Norse lore, a local colour sensibility and the animal motifs of the medieval Baldishol Tapestry (c. 1100) and 18th-century Gudbrandsdalen tapestries.

The Suitors (1892), Gerhard Munthe. National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design, Oslo

Trained as a painter, Munthe was initially influenced by the flat compositions of French Synthetism and Japanese art. His early series of ‘fairy-tale watercolours’ combined these tendencies with images of wildness and the mythological grotesque. Long-snouted trolls haunt the sky in In the Giant’s Lair (1892), while in The Suitors (1892) three girls are approached by prowling polar bears, their hair transformed by fright into something resembling a cartoon electric shock. When these paintings were exhibited at the ‘Black and White Exhibition’ of 1893 in Kristiania (now Oslo), the critic Andreas Aubert compared them to traditional Norwegian tapestries. Munthe initially resisted a turn towards textiles, but was soon working with the weavers Augusta Christensen and Kristine Johannessen to transfer his designs. This shift of medium initiated a lifelong practice that saw Munthe’s paintings and drawings executed by collaborating craftsmen across a dizzying range, from tapestry to book illustration, typefaces, interior design, architecture, furniture, silverwork, stained glass and even a Viking monument in Rouen.

Kokkin’s subtitle, ‘Norwegian Pioneer of Modernism’, sits uneasily with Munthe’s emphasis on traditional and national crafts, notwithstanding his resistance to traditional rules of perspective. But his mythic material prompted a more obviously modern concern with dreams and psychological disturbance, as epitomised by The Tracks of Blood (1892) and Afraid of the Dark (1892–93). In this respect he shares something with second-generation Pre-Raphaelites, among whom a flattening of the picture plane, and a loosening of the distinction between figure and pattern, afforded a less defined sense of self and a new role for the unconscious. The connection in Munthe’s work between medievalism and modernity brings William Morris to mind. But Morris prompted an anxiety of influence in the Norwegian artist, a complex that this book registers without ever quite resolving. We are initially told that ‘Munthe has often, somewhat misleadingly, been compared with Morris’; yet the comparison recurs across subsequent pages, refused but never quite laid to rest.

The entrance hall, Leveld (1902), Gerhard Munthe. National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design, Oslo

Like Morris, Munthe believed in a total or integrated art, and he identified the home as the site of this experiment, seeking to design not only his own house but the furniture and hangings inside it. He too was in the business of reviving vernacular crafts, notably through the Norwegian Home Crafts Association (established 1891). In the wake of an exhibition of Walter Crane’s work in Kristiania in 1896, Munthe responded to claims ‘that my art resembles that of a couple of Englishmen’. ‘Actually,’ he observed, ‘it was only later (after the Black and White Exhibition) that I saw their works, but even this is irrelevant, since they follow a different principle.’ Perhaps he protests too much. But Munthe was right about their differences: ‘Time and again,’ he complained, ‘I am expected to be my own craftsman – my own Morris.’ Munthe was a designer in the industrial mould: he sketched mental conceptions in the portable medium of watercolour, and found others to execute them in solid stuff. In this respect, he rejected Morris’s commitment to uniting hand and mind, prior vision and final product.

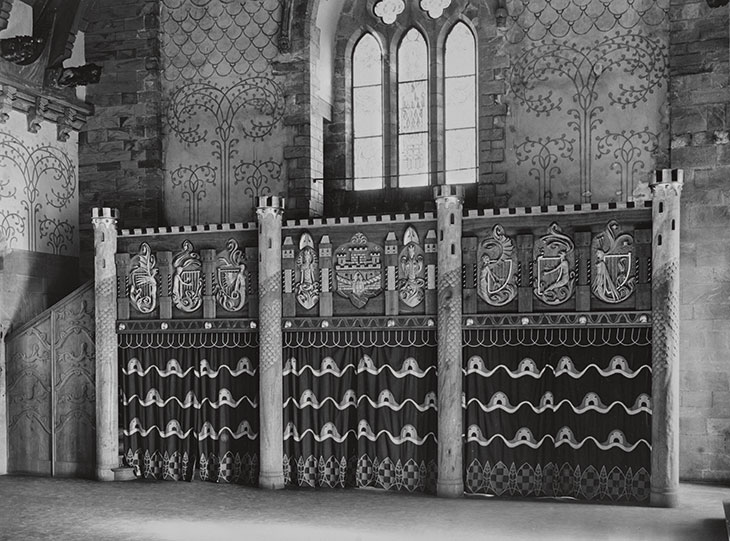

This book performs a welcome task in making Munthe better known to Anglophone audiences. The text has been translated, and this occasionally shows; it also dwells excessively on the detail of who said what and why, while neglecting the broader shape of Munthe’s life and career. But it comes to a striking and suggestive conclusion in the tale of Bergen’s Håkonshallen (King Håkon’s Hall), a vast medieval banqueting hall the embellishment of which Munthe was commissioned to oversee. Such was the public unease at the prospect of alterations to the historic fabric that work did not begin until 1910, a decade after initial steps were taken. And it was not until 1916 that the interior was complete. The very next year plaster was found flaking from the damp walls, prompting further work. The hall was eventually inaugurated for use in 1929, the year of Munthe’s death.

The musicians’ gallery, Håkonshallen, Bergen, photographed after Munthe’s decoration of the hall and before its destruction in 1944. Photo: O. Væring

But this was not the end of the story. Fifteen years later, on 20 April 1944, a Dutch steamer loaded with German munitions exploded in the vicinity, blowing off the hall’s roof and destroying the historical fantasy inside. It is tempting to interpret this cataclysm in the light of creative destruction, a curiously modern judgement on fairy-tale accretions, once again revealing the building’s deep surface of medieval masonry. But Munthe’s legacy is broader and more deserving than this fateful incineration implies. The surrealistic currents of his work, his reimagining of pattern and his commitment to the creative translation of design as a distinct practice connect him to British Arts and Crafts practitioners, while insisting equally on a differentiation, on a distinct vision that reveals the 19th-century roots of modern Norway’s creative rebirth.

Gerhard Munthe: Norwegian Pioneer of Modernism by Jan Kokkin, translated by Arlyne Moi, is published by Arnoldsche Art Publishers.

From the November 2018 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home