Palazzo Te, sitting on the edge of once-malarial Mantua and designed inside and out by Giulio Romano for his patron Marquis (later Duke) Federico Gonzaga, is a rather unlikely enterprise. It’s a building characterised by architectural licence, and its wildly inventive interior decoration provides us with painted horses, fictive sculpture and a great, licentious tumble of bodies. It can be wonderful on a summer’s day, but its playfulness is rather unrelenting during one of Mantua’s wispily damp winters; its jokes, sometimes a little smutty, fall flat when there’s only a tiny, chilled audience present. This is a place that needs people. Now some of its rooms are occupied again to stage, for the first time, an exhibition. ‘Giulio Romano: Art and Desire’ (until 6 January 2020) is exactly the right show in exactly the right place – and as a result the entire propagandist pleasure palace is enlivened, its exuberance carefully conceived.

This exhibition itself encourages ribaldry, so I hope its curators will forgive my observation that it is small but perfectly formed. Not counting Palazzo Te itself, the show has just 44 exhibits, brilliantly selected by Barbara Furlotti, Guido Rebecchini and, building on her groundbreaking research for ‘Art and Love in Renaissance Italy’ at the Met (2008–09), Linda Wolk-Simon. It is only a shame that one or two of Giulio’s most pertinent drawings couldn’t have been spared; they are displayed across the city in a more conventional but illuminating exhibition at Palazzo Ducale (‘Con Nuova e Stravagante Maniera’; until 6 January 2020).

At Palazzo Te we witness two young men standing side by side, planning a generational artistic leap. They were almost exactly the same age, around 25, when they started working together, if Giulio was indeed born in 1499 as the documents of his death suggest. One was the ruler of a small Italian city state and the other a precociously talented painter. Both had been in Rome – Federico as a political hostage to Pope Julius II, Giulio as apprentice or very young assistant to Raphael. Thus there was a distinct parallelism; even if they didn’t know one another, they had moved in the same circles, which contained figures such as the archetypal erudite courtier, Baldassare Castiglione.

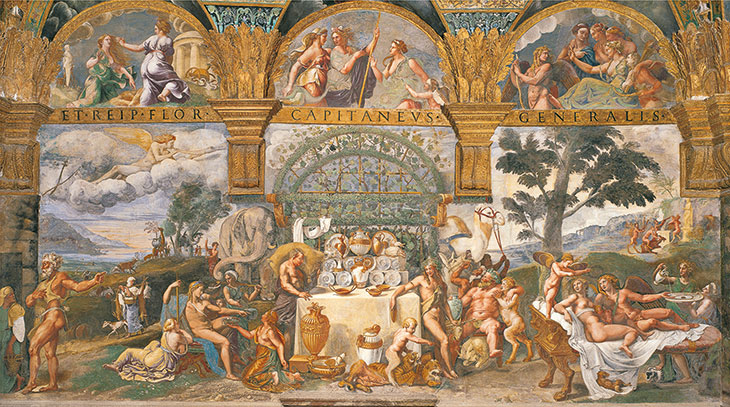

The south wall of the Sala di Psiche, Palazzo Te, Mantua, Giulio Romano and workshop

In 1521, the year after Raphael’s death, Federico wanted to attract to Mantua both of Raphael’s heirs, his closest assistants, Gianfrancesco Penni and Giulio Romano. In 1524, he finally got Giulio. The artistic language they devised was inventive, courageous, witty, bounteous, theatrical (in that it is full of visual and material tricks that demand an engaged audience to make them work) and, above all, sexy. It found its fullest expression at Palazzo Te. There, the court and its guests could enjoy a room telling the story of the Fall of the Giants, Giulio’s immersive masterpiece of crushed Titans and powerful gods – great bodies seen in the boldest possible foreshortening. There too, Giulio and his workshop painted their brilliant erotic picture-novel – the story of Cupid and Psyche – with the amatory, the luxurious and the illusory brilliantly coexisting. In another room, we even get a glimpse right up Apollo’s skirts as he traverses the heavens.

It’s this last strand that the exhibition’s curators have chosen to explore. This is a show that is, on the face of it, mostly about sex and the ways of seeing it. At its simplest, this is an analysis of a surge of Renaissance testosterone. There is real wit here, and it’s of an unquestionably bawdy character; like the Palazzo Te itself, this exhibition lays out a buffet of boobs, bums and bollocks that might be surprising for devout believers in an entirely serious, classically inspired Italian Renaissance. It’s evidently not only four-year-olds who think that willies are funny, or just adolescents who notice that ancient marble nudes can be rather improper. And, as the works here remind us, sex gives us views of each other’s bodies that have nothing to do with dignity. The exhibition identifies a kind of letting-go, and in doing so helps us understand better the spirit of Giulio’s building. His is an Architecture released of her constructive garments.

If Palazzo Te has all the energy of a bachelor bash, it was achieved with much greater subtlety. This exhibition makes us realise that Giulio made a number of rather serious decisions in serving his young lord at Palazzo Te. In these days of a groping US president, elected nonetheless, we should heed Rebecchini’s connection of the ‘erotic and political dimensions [in this art of sex], united by shared expression of the idea of domination’. Giulio’s art is all about power and potency – male generative power, with the sexual morphing into the signorial.

Venus and Adonis (c. 1516), Giulio Romano. Albertina, Vienna

Thus it is important to make the distinction that the curators rightly insist upon, between the titillating, the erotic and the pornographic. The rumbustious rumpy-pumpy of Giulio Romano, in style as well as content, is not the same as the more polite titillation of Raphael himself or of artists such as Perino del Vaga, Giulio’s sexually anaemic fellow workshop graduate. The show traces a line of sex-inspired image-making that begins, the curators argue, with Cardinal Bibbiena’s stufetta (heated room) at the Vatican and the decoration of Agostino Chigi’s Roman villa, now known as the Farnesina, both Raphael workshop efforts that involved Giulio. Compared to where Giulio would later take it, this erotica feels rather tame, however. In his red chalk Venus and Adonis of around 1516, for example, physical congress is codified as a chuck on the chin, a squeeze of a breast, with the goddess resting between the young man’s thighs. It’s very nearly respectable.

All the same, Raphael was the key precursor, a male artist acutely aware of himself as generating female beauty, both creative and procreative. His contemporaries characterised him as almost feverish with lust, but in his paintings and drawings, the desire becomes delicate, the allure legitimate. The painting known as the Fornarina responds to a literary ideal, a variant on traditional Petrarchan image-making exploring love and loveliness. It was probably left unfinished at Raphael’s death and completed by Giulio. This nude figure is a subtle synthesis of the real, the ideal and the sexually available (since nice young women didn’t take off their clothes in front of men). The signature on her armband declares her to be owned as well as invented by Raphael; such images are still about the domination of the mature male, about the command of an artist in charge of his imagery.

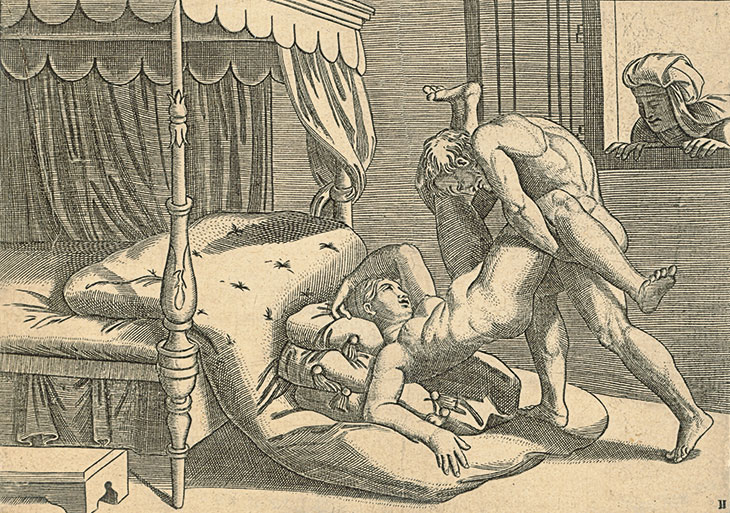

For Giulio, making art, not just erotica, became an earthier thing – a more precarious, percussive performance. But, though it is brave in what it represents, Giulio’s art rarely tips into the blatantly pornographic. This might seem an odd claim to make for the artist who, after all, was the designer of the most celebrated series of sex scenes of the Italian Renaissance. Back at the Farnesina, it was an ancient sculpture of a satyr sexually assaulting a boy that inspired I Modi, the sequence of suppressed prints designed by Giulio and that landed Marcantonio Raimondi, Raphael’s chief translator into print, in prison. (This story comes from Pietro Aretino, who wrote the smutty poems that accompanied the engravings and somehow made them worse; he is not a source to be relied upon.) Giulio’s designs described a number of adventurous positions for heterosexual coupling. The only surviving fragments, in the British Museum, have sadly been exhibited too recently to travel again, and the copies in the celebrated Toscanini volume of around 1556 are another absentee here. Usefully, however, one of a handful of earlier prints copying Raimondi is included.

Position 9 of I Modi, (reversed copy) after Marcantonio Raimondi (1530–40). Albertina, Vienna

I Modi have long been linked to the group of coin-like spintriae, here categorised as ancient Roman triumph (rather than brothel) tokens. I wonder why no one is concerned that most, if not all of these, appear to be cast rather than struck, as Roman coins and tokens surely should be. Are these apparent survivors actually copies made in Renaissance Italy? Are they fakes? The sexes of the protagonists are not always clear, and this they have in common with a small group of drawings displayed here that we might nowadays categorise as fluid in more sense than one – such as the pen-and-ink study by Parmigianino from a private collection in Paris, even though it is based on Giulio’s Position 8.

In fact, the designs for I Modi compare tellingly with a work such as Raimondi’s engraving of a woman with a dildo from around 1520. The only surviving example is torn and repaired, a masturbatory image of masturbation, a work of art surely made to be held in one hand. It’s private and, when encountered in a public space as here, distinctly cringe-making. By contrast, Giulio’s erotic art, even in its more private manifestations, thrillingly treads the line between the socially acceptable (humour is part of this) and the embarrassing. Such is the power of the word, that Aretino’s poems made these prints about just one thing. It would be silly to pretend that they are not about desire, but that’s not their only meaning. Giulio actually gave us rather discreet flashes of genitalia – and they are mostly ‘adult warning’, rather than X-rated. And, in fact, these images both are and represent balancing acts. Their meetings of bodies are often difficult and strenuous, and Giulio ensures that our sense of energy and effort extends to the bold foreshortening of torsos, bottoms, legs and arms. These are sex scenes that are proposed as bravura artistic inventions.

It is important to remember that, banned though they may have been, I Modi constituted a well-advertised starting point, a calling card for the artist. The title of the series has a portmanteau quality, encompassing ‘the styles’, ‘the idioms’, ‘the ways’, and ‘the manners’; Giulio’s subject-matter is only ever a short jump from his style. Throughout, his art has an unabashed swagger that links the aesthetic to the sexual. There’s a touch of the young Brando, Belmondo or Gere to him – a kind of artistic athleticism or prowess. There was always an aspect of performance, too. Palazzo Te went up in no time at all, and the bold couplings of motif in Giulio’s designs for silver, which are such a prominent feature of his Sala di Psiche, were unprecedented. His art can sometimes seem rather crude, brutish in the strength of line, with physiognomies that are a little Palaeolithic. It is intensely masculine – fantasy combined with forcefulness – and it’s no surprise that, in counterpoint to his erotica, there are so many scenes of conflict and violence.

These qualities or associations of Giulio’s art, and others – potency, virility, creative licence, lavishness – provided Federico with a macho visual persona. Studies of Renaissance masculinity have helped us see the phallic in art as less straightforwardly sexual and more about power. The pen-brush-penis analogy, familiar in the period, is resonant here. But, more than that, Palazzo Te rehearses the idea that an observed male sexuality could stand as emblematic of Federico’s larger dominion.

Two Lovers (c. 1524), Giulio Romano. State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg

The centrepiece of the exhibition is the spalliera panel from the Hermitage, Two Lovers, the painting that set this agenda for artist and patron. It was very likely commissioned, via Baldassare Castiglione, for Federico’s Palazzo di Marmirolo, his love pad for trysts with his mistress Isabella Boschetti. Castiglione was to choose the subject matter – ‘not things of holiness, but some pictures which are vague and beautiful to look at’. The work is, unusually for Giulio, painstakingly executed, sating the viewer with its abundant detail: the rumpled, untucked sheets, the mass of heavy curtains, the discarded slippers and chemise, the golden ass on the bedhead, the voyeuse with her key and humpy dog.

With this picture Giulio was casting himself as a court painter, entirely modern, but also looking back to the heritage of his great predecessors in Mantua, Pisanello and Mantegna, both called upon to execute fully autograph painted jewels like this one. Another pleasure of this exhibition is to look backwards from the Palazzo Te to the great quattrocento projects of those artists at the Palazzo Ducale and to realise that Giulio was building on a visual tradition. They too played games with reality, illusion and flights of fantasy, like the gathering of dogs and horses, courtiers and dwarfs in Mantegna’s Camera degli Sposi, weaving in and out of their space, the painter’s imaginary landscape and our own world. And their pictures also introduce notes of comedy, jokes like Pisanello’s fallen soldier, foreshortened underwear-first, in his great Sala at the Palazzo Ducale.

Palazzo Te is more than a little outrageous at times. But, like those rooms frescoed by Mantegna and Pisanello, these were public spaces; they needed to be a romp, rampant but still capable of hosting an emperor. This clever exhibition shows us Giulio’s calculated interlacing of sensual and visual imagination, of memory, reality, fantasy and fleshly gratification – and demonstrates how that admixture underpins all his work. It explores ways – modi – of viewing art that are arguably just as important as the well-understood hierarchy of Christian spiritual modes of viewing for our understanding of Renaissance visual culture. Just as Federico demanded, these works are ‘not things of holiness’, precisely the opposite; nonetheless, they too inscribe a route from the physical and realised to realms of sense, vision and imagination – and sometimes back again.

From the December 2019 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home