From the February 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Francisco de Goya has been cast in many roles: the liberal thinker satirising the monarchy; the court painter bent on self-promotion; the proto-modernist rebelling against the academy; the deaf madman daubing the walls of his country estate with ghoulish fantasies. In Goya: A Portrait of the Artist, Janis Tomlinson sets out to write a biography without embellishment or romanticisation. For this she turned not to the artworks, as almost every previous biographer has done, but to the archive, compiling all known documents – letters, invoices, wills etc. – concerning Goya’s movements and using them as points on a map to guide us through his complex life. Tomlinson acknowledges the difficulties of this approach in her introduction: ‘Having written a first draft […] I realised that without going further, the book did no more justice to Goya than a curriculum vitae does for any individual.’ The version that made it to the printers is nothing short of an academic triumph.

Her approach is refreshing, allowing the letters and other archive documents to speak for themselves, revealing the many contradictions and oversimplifications in the narratives of other biographers. Goya’s sheer productivity in a vast range of media and subjects has led art historians to compartmentalise and specialise. With volumes and exhibitions focusing solely on his etchings, tapestry cartoons, portraits or cabinet pictures, it is easy to forget that these categories are arbitrary. Tomlinson does not forget: instead she deftly assembles Goya’s various commitments to create an image of an artist frantically juggling a dozen projects at once, as well as commitments to friends, the chasing of invoices and the other tasks that accompany the life of a productive painter. One has to marvel at the detailed records that allow for this type of biography. Tomlinson outlines how, in a single month in 1778, Goya was revising a tapestry cartoon, making etchings after Velázquez, fulfilling commissions for the royal household and supporting his wife, Josefa, through a miscarriage.

A native of Zaragoza, Goya moved to Madrid in 1775, where he spent the next five decades. He served three Bourbon monarchs and witnessed the bloody Napoleonic occupation, the restoration of the despotic Ferdinand VII and the short-lived constitutional parliament. The ‘portrait of the artist’ painted by Tomlinson is that of a man able to adapt to an ever-changing political landscape. Her prose interweaves personal biography and major historical events with brief interludes of artistic description that whet the visual appetite. Reading it is like walking on a frozen lake, aware of the scholarly depth beneath but safe on top of the thick ice. Bite-size chapters transform the tome into a digestible and enjoyable read.

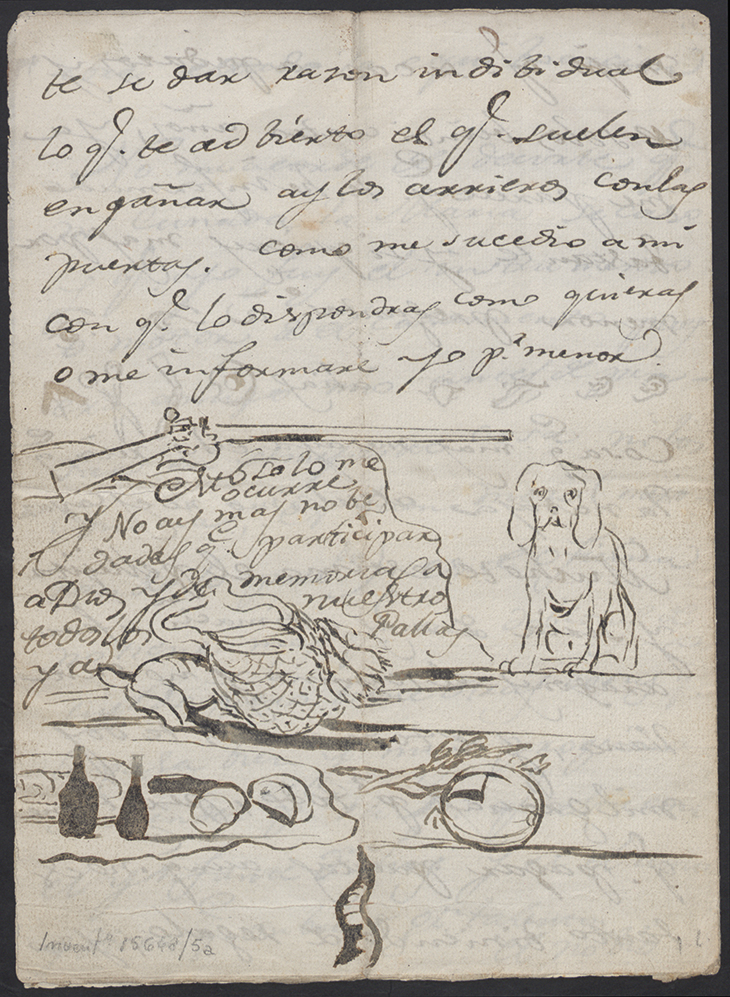

Letter written by Goya to Martín Zapate, from between 1783–89. Biblioteca Lázaro Galdiano, Madrid. Photo: Museo Lázaro Galdiano, Madrid

A complex cast of supporting characters is brought to life in vivid detail, none more so than the Aragonese businessman Martín Zapater. Goya’s letters to Zapater from 1775–99 shape the first half of the book. They are passionate things, full of Goya’s hopes, fears and feuds in Madrid, as well as bawdy jokes and occasional sketches. Tomlinson dismisses the theories of homosexuality, but she does read Zapater’s death in 1803 as a turning point in Goya’s emotional life. It coincides with Spain’s turn away from liberalism, the rise of Napoleon across the Pyrenees and a growing instability as friends and patrons are exiled or imprisoned.

Nuance is a constant feature of this book. An early example lies in Goya’s ill-fated frescoes for the church of El Pilar in his hometown of Zaragoza. His brother-in-law, Francisco Bayeu, was initially given the commission for the decoration of four domes in the church. The young Goya took charge of one of these domes, but the committee deemed it unfinished and ordered Bayeu to retouch the fresco. Goya’s anger is recorded in a number of letters and led to an estrangement both from his in-laws and his native city. The story has long been read as that of a backward audience unable to see the genius in Goya’s new style. Tomlinson rejects this idea: ‘Goya’s fresco at El Pilar did not anticipate [his later] works: it is a single essay and a failed one in the eyes of patrons and of the community.’ The book is full of such moments where Tomlinson casts down the ‘cult of Goya’. It is almost lawyer-like: providing the facts, the context and carefully worded interpretation, with the reader as jury to cast the final verdict.

Regina Martyrum cupola, 1780–81, Francisco de Goya. Basílica de Nuestra Señora del Pilar, Zaragoza. Photo: Album/Alamy Stock Photo

The no-nonsense approach is in full force in her analysis of the so-called Black Paintings (a title Tomlinson purposefully avoids). The murals made on the walls of Goya’s estate, La Quinta del Sordo, have long been romanticised as the work of a madman, isolated with only his memories of war and death for company. Saturn gnawing on the limp body of his child, the he-goat devil preaching to a wailing crowd and the hunched floating Fates are not the idyllic scenes one would expect to find in a country retreat. Tomlinson disagrees. She compares them to the phantasmagoria popular with audiences in Madrid since the 1790s. In this context, Tomlinson argues, Saturn chewing on his son was less shocking then than it is for us today. However, in the noble effort to dispel the myth of Goya’s madness – of which there is no evidence in his letters – the pendulum may have swung too far the other way. The artist was a self-proclaimed genius who took pride in his powers of invention. The murals fit into this world alongside the Disparates, and many other inscrutable drawings, prints and paintings. To explain these as products of their time is to dismiss this invention.

Goya saw the world with a sharpness of wit that still cuts us today. If this book has a fault, it is that the artist’s emotion is sometimes lost in Tomlinson’s forensic, academic scholarship. For the uninitiated, those who enjoy Goya’s art but are not yet fanatical devotees, Robert Hughes’s biography may be a better place to start. But make no mistake, this book is a tour de force. For those of us who are already card-carrying members of the Goya fan club, it provides judicious insights into the documentation that work in tandem with our own passion for the pictures. In a world brimming with books on Goya, this will surely stand as the definitive biography for years to come.

Atropos or The Fates (1820–23), Francisco de Goya. Museo del Prado, Madrid

Goya: A Portrait of the Artist by Janis A. Tomlinson is published by Princeton University Press.

From the February 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home