From the June 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

A large photograph greets you on entering: a naked woman sitting atop a wooden crate, her knees angled to one side, a hand resting behind. She has a small belly and breasts; the skin of her hands, face and neck is burnished brown, likely from her long walks through Paris in the sun. Her chin is slightly upturned and her expression, though rather flat, is certainly not embarrassed.

The photograph has never been published before; this is, quite literally, Gwen John as you have never seen her. This is her autonomous, erotic body; a body she put to work as an artist’s model to earn money after her arrival in Paris in 1904, a body she sketched and painted, and, in her relationships with both men and women, a body she enjoyed. She wrote freely to Auguste Rodin of her sexual fantasies during their relationship; in her letters, she called him ‘maître’. Yet there is something curiously veiled in her expression, as she perches on her makeshift stool. This, too, is the artist who relied on quiet and orderliness, organising her palette into subtle spectrums of browns and greys as Whistler taught her – who preferred her own company and protected her privacy and solitude at all costs.

Autoportrait à la Lettre (c. 1907–09), Gwen John. Musée Rodin, Paris

The photograph highlights a particular difficulty in discussing the lives of women artists and their work: to show them as ambitious and connected, while independent of those (mostly, men) who helped or hindered their careers. Putting Gwen John at the centre of modern Paris – and its fascination with the eroticised female form – does her much justice and counters her reputation as the fragile recluse, model and muse to Rodin (who had the names of 90 female life models on his books). However, it’s possible to put too much energy into new narratives. There is little of the other Gwen John here – the one who wrote lyric-like notes on colour (take March 1923: ‘Elderberries & their yellow leaves & pink campiens & their cendre bleu green leaves’), personal dictums (including the revealing ‘Rules to Keep the World Away’), prayers and meditations. The inclusion of more notebooks (only one is on display here) would better indicate the richness and complexity of her interior life, in which she carried the fervour of her love affairs into her religious faith and her painting.

A Corner of the Artist’s Room in Paris (c. 1907–09), Gwen John. Sheffield Museums Trust

Gwen John’s paintings are beautifully compact. Detaching herself from the Slade, and leaving London (where her brother, Augustus John, remained), she got into her stride while walking through France in 1903 with her friend Dorelia McNeill. The women intended to reach Rome, but made it only as far as Toulouse, where John painted her companion in a darkened interior, wearing a black dress, a pale pink ribbon illuminating her face. The half-moon scoop of McNeill’s neckline is pale and luminous, the brightest spot. Each painting contains a moment like this, where the reserves of palette and composition are breached and something concealed breaks through. In A Lady Reading (1910–11), a 15th-century face sits atop a contemporary Parisian woman’s body, her leg resting on a basket chair. Light filters from the window, a breeze stirs the room. This woman, pale, studious, is a Madonna of sorts, awaiting her interruption; a transformation will take place.

Dorelia in a Black Dress (1903–04), Gwen John. Photo: © Tate

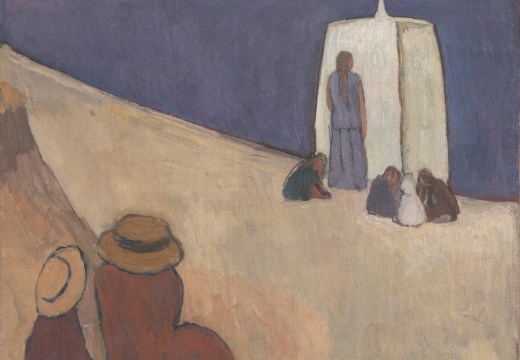

In the exhibition, this painting is placed alongside others of its kind: an interior with figure by Hammershøi, another by Vuillard. This is a story of association, not isolation, reinstating Gwen John to the narrative of Parisian experiments with the interior, the female figure and modernism’s emerging interest in spiritual feeling. (On the opposite wall, beyond a series of Rodin’s life-drawings, there is the pleasure of a nude sketch by Paula Modersohn-Becker.) Yet John’s figures were always different. Her interiors are pared back, her paint spare. To run your fingers over the surface of Young Woman in a Red Shawl (1923) would be to feel as if you’re touching a fresco.

The Nun (c. 1915–21), Gwen John. Photo: © Tate

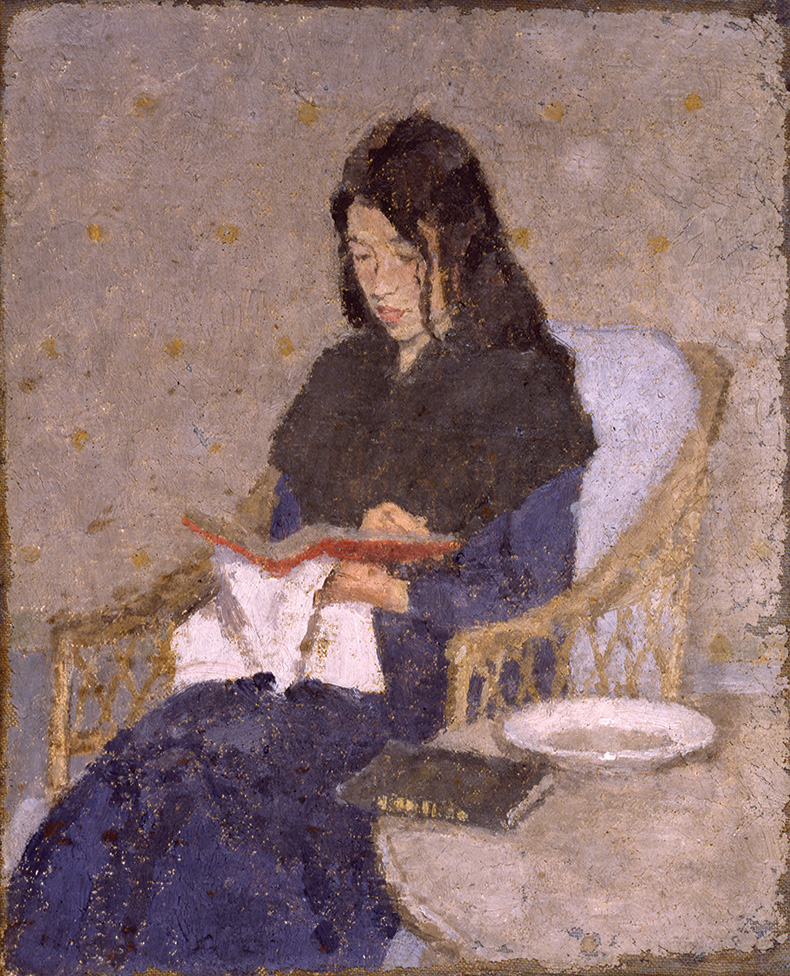

In 1911, after her relationship with Rodin ended, John moved to Meudon, a village on the outskirts of Paris. It was here, two years later, that she converted to Catholicism. ‘I must be a Saint in my work,’ she wrote, calling herself, ‘God’s little artist’, and ‘A diligent worker’. Her paintings from this period are among the most interesting. She worked in series: six paintings of Mère Poussepin, the Dominican nun who in 1696 founded the local order, seen here with white sculpted sleeves; a further eight of a young sister, eyes gleaming beneath her headdress. Then came her ‘convalescent’ pictures – ten paintings between the late 1910s and the mid ’20s of a young woman in blue, quietly reading. Was Gwen John turning her back on the turbulence of the world? Rather, writes Alicia Foster, these were war works, and the artist’s most direct engagement with what was happening around her, the woman’s presence conjuring the space between deprivation and recovery. During this period, John was recognised for approaching her own kind of old-modernism. Between 1910 and 1924, her work was bought by the Irish-American collector John Quinn, who secured her inclusion in the Armory Show in New York in 1913.

The Seated Woman (The Convalescent) (c. 1910–20), Gwen John. Ferens Art Gallery/Hull Museums

Gwen John died in 1939, leaving 200 small, exquisite oil paintings. By the 1930s, she was mostly isolated in Meudon; her patron was dead and she vowed never to show her work again in Paris. Nuns and churchgoers proliferate in her watercolour sketches, as do figures walking slowly, hand in hand, along country lanes. (These small landscapes were a last evocation of her mother, also a painter, from her childhood in Wales.) She painted the buildings of Meudon glowing moonily at night; the stillness prevailed.

Perhaps what this exhibition allows us is a glimpse. Now we have witnessed Gwen John, naked, in Paris, exposing herself to the experiments of the day. What’s been seen can’t be unseen. It lends new perspective to her portraits of women, of models in plain clothes, convalescents and nuns. They are works of control, self-knowledge and immense feeling. Hearts beat beneath those blue robes; behind those eyes, thoughts fleet. The two sensibilities of Gwen John are brought together and can coexist. Here she is, then: the artist who bared all and yet retained her quiet mystery.

‘Gwen John: Art and Life in Paris and London’ is at Pallant House Gallery, Chichester, until 8 October.

From the June 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home