At the heart of the recently renovated wings of the National Gallery of Ireland stands a new stained-glass room, dominated by Harry Clarke’s large Mother of Sorrows (1926) window. Other works produced during Clarke’s short but remarkably productive career (he died in 1931, aged just 41) are prominently displayed in Dublin’s Hugh Lane Gallery and in the Crawford Art Gallery in Cork. Recent reprints of his book illustrations not only feature in these galleries’ gift shops but also have a near-permanent place in the window of Dublin’s largest bookshop, Hodges Figgis. It is clear that Harry Clarke and his chosen media – stained glass and book illustration – are now central to any sense of early 20th-century Irish art. Less apparent is quite what Clarke’s singular work offers to its now undoubtedly considerable public. There is something overwhelming, occult even at times, about its awesome intricacy. It stands stylistically at a remove, too, from the work of most of his contemporaries. Yet by carefully placing Clarke amid the turbulent period of Irish history he lived through, not least through much valuable digging in the archives, this beautifully designed and illustrated collection of essays helps one begin to understand rather than simply be beguiled by such startling excess.

At the heart of the recently renovated wings of the National Gallery of Ireland stands a new stained-glass room, dominated by Harry Clarke’s large Mother of Sorrows (1926) window. Other works produced during Clarke’s short but remarkably productive career (he died in 1931, aged just 41) are prominently displayed in Dublin’s Hugh Lane Gallery and in the Crawford Art Gallery in Cork. Recent reprints of his book illustrations not only feature in these galleries’ gift shops but also have a near-permanent place in the window of Dublin’s largest bookshop, Hodges Figgis. It is clear that Harry Clarke and his chosen media – stained glass and book illustration – are now central to any sense of early 20th-century Irish art. Less apparent is quite what Clarke’s singular work offers to its now undoubtedly considerable public. There is something overwhelming, occult even at times, about its awesome intricacy. It stands stylistically at a remove, too, from the work of most of his contemporaries. Yet by carefully placing Clarke amid the turbulent period of Irish history he lived through, not least through much valuable digging in the archives, this beautifully designed and illustrated collection of essays helps one begin to understand rather than simply be beguiled by such startling excess.

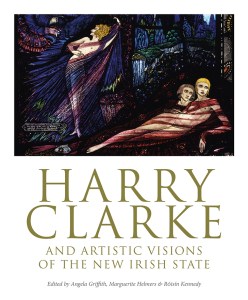

St Gobnait Window (detail) (1916), Harry Clarke. Honan Chapel, Cork. Photo: Kelly Sullivan

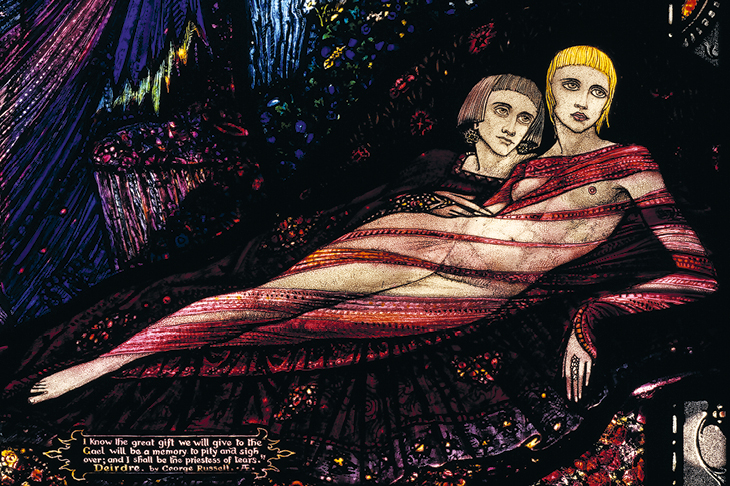

Born into a commercial stained-glass window business, Clarke benefited from a remarkable period of art education in Dublin. At the Metropolitan School of Art he took life-drawing classes with William Orpen and was instructed in stained-glass design by A.E. Child. A former assistant of the leading British stained-glass artist Christopher Whall, Child had come to Dublin in 1901; to remarkable effect, he helped conjure Ireland’s exceptional Arts and Crafts stained-glass industry, also teaching the likes of Wilhelmina Geddes and Michael Healy. The cultural energy and idealism at large in pre-revolutionary Ireland lay behind Clarke’s first major commission, a series of 11 windows for the Honan Chapel in Cork. Ann Wilson’s opening essay reframes these windows as diverging from Irish Catholicism’s earlier 19th-century devotional revolution, which had sought to bring the Irish church into line with Vatican-approved norms. The fantastical incorporation into Clarke’s depictions of early Irish saints with their associated cults and miracle stories stands at odds with all this. The legend of St Gobnait unleashing bees upon a band of thieves, for instance, is evoked via ‘giant bees and tiny figures of frightened robbers peering out anxiously behind the blue-robed saint, whose pointed, impassive profile, unnaturally long slim hands and geometrically stylised body give her an otherworldly, non-human appearance’. For a brief period, such a vision precariously coalesced with Catholic as well as nationalist Ireland.

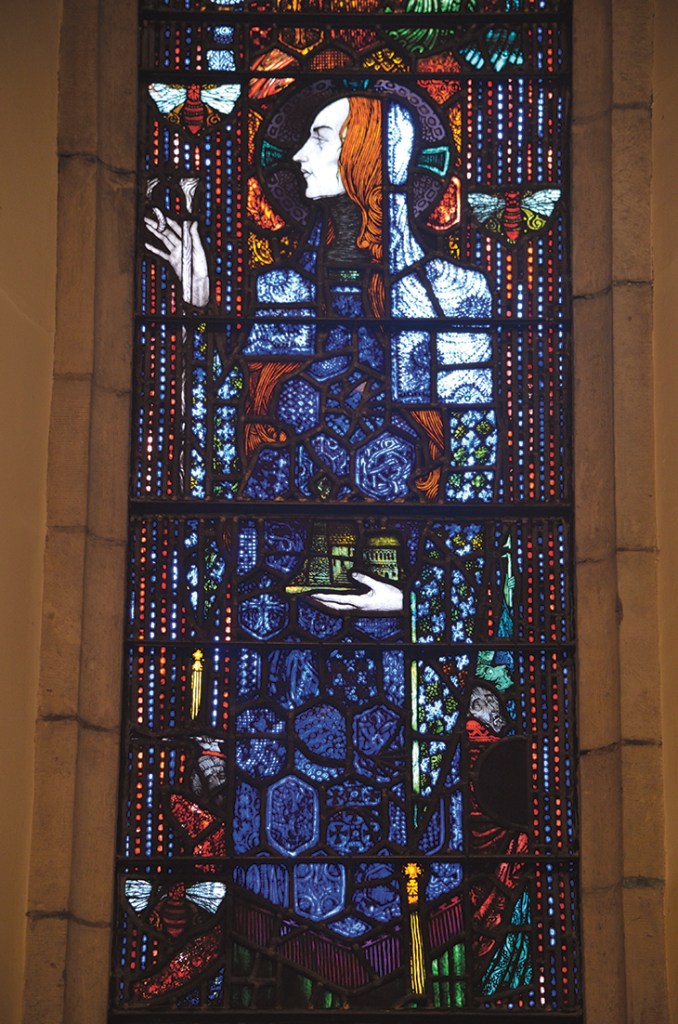

As the other contributors show, however, complications to such accommodations were on the horizon, for Clarke’s own work and in terms of the broader cultural weather. This same St Gobnait window is persuasively read by Kelly Sullivan in relation to Clarke’s early use of ‘a particularly Irish idiom’ of natural imagery. Yet more grotesque and degenerate images start to crop up in the 1920s. In an illustration of the witch’s kitchen scene (Methinks, a million fools in choir / Are raving and will never tire) in a 1925 printing of Goethe’s Faust, the newly young protagonist ‘stands beneath a canopy of slimy sexually suggestive larval growths sprouting eyes, tentacles and rodent-faces’. Sullivan links such images of disease and decay to Clarke’s own doomed struggle with tuberculosis. Elsewhere in the volume, this darkening shift in sensibility is also traced against the backdrop of the aftermath of the First World War and of conflict in Ireland.

Methinks, a million fools in choir / Are raving and will never tire (1925), Harry Clarke, illustration for a translation of Goethe’s ‘Faust’, published by George C. Harrap & Co., London.

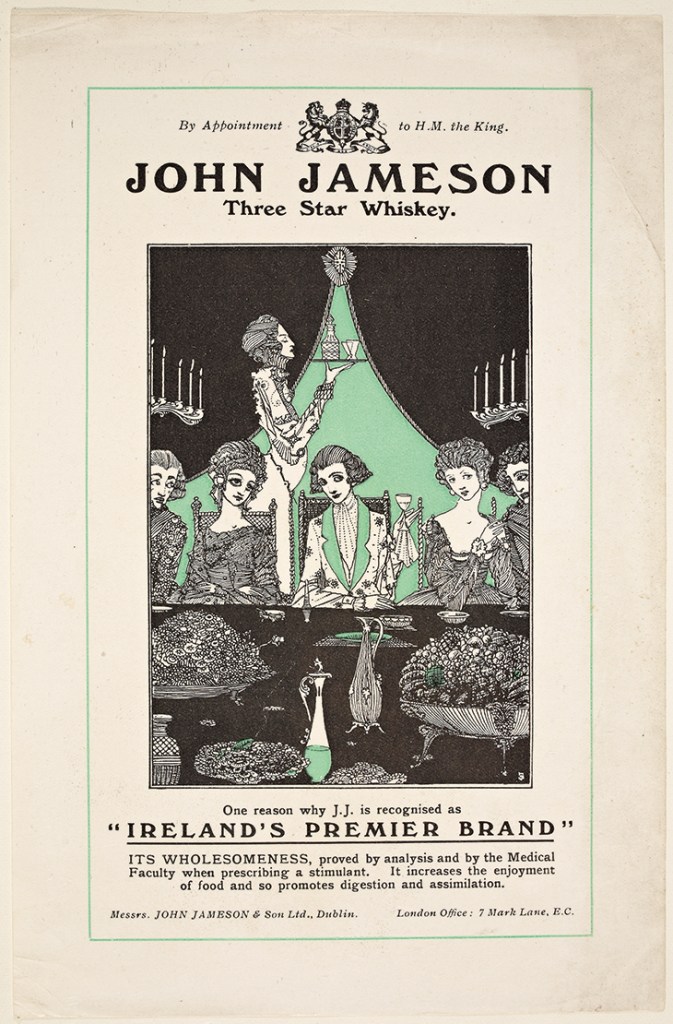

A brighter side to the artist’s work in the newly emerging Irish state is also highlighted. Angela Griffith’s account of Clarke’s playful promotional illustrations for the Jameson distillers gives a fascinating portrait of an artist ‘who straddled comfortably the world of both industry and art’ within an Ireland seeking to assert itself not only as an independent nation but also as an appealing brand. Similarly, Kathryn Milligan places Clarke within a Dublin that, after the Irish civil war, participated in some respects in an age of irreverent modernist experimentation. One complexity the book repeatedly attempts to address, indeed, is Clarke’s relationship to symbolist and modernist artistic currents elsewhere. More searching and expansive comparisons, however, might have helped better define Clarke in this regard. It is striking, for instance, how similar aspects of Clarke’s work are to certain works by the Dutch artist Jan Toorop. Yet across this volume, the only parallels drawn, in passing, are long-familiar ones to famous figures such as Audrey Beardsley and Gustav Klimt.

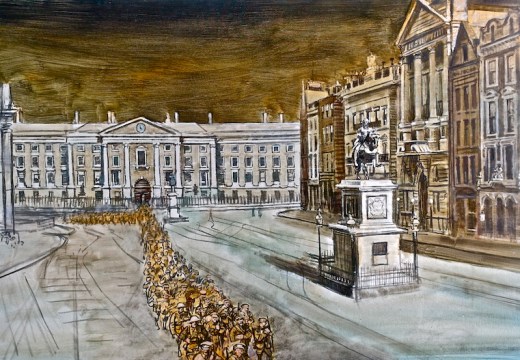

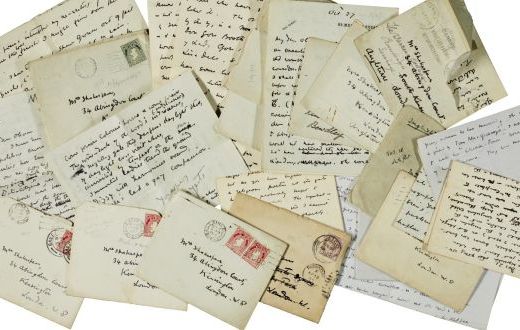

Whatever the nature of Clarke’s aesthetic, his uneasy position – at the centre of Irish culture while feeling increasingly alienated from the Irish Free State – is clear in the notorious case of his Geneva Window. Róisín Kennedy painstakingly pieces together how Clarke came to be commissioned by the government to create this gift for installation in the Geneva headquarters of the International Labour Organisation. Clarke proposed stained-glass panels illustrating 15 scenes from works by contemporary Irish writers as ‘an evocation of work as an imaginative and creative endeavour’. Yet several of the decidedly erotic illustrations Clarke chose to make fell foul of a regime increasingly in thrall to Catholic proscriptions on sexuality, to the extent that it was censoring some of the writers his work celebrates. Though the government had no intention of displaying the window in Geneva or Dublin, it nevertheless acquired it soon after the artist’s untimely death in 1931. Eventually, Clarke’s family bought it back: it is now on public display in the Wolfsonian museum in Miami. Perhaps it will be shown in Ireland one day.

Advertisement designed by Harry Clarke in 1924 for John Jameson three-star whisky.

Harry Clarke and Artistic Visions of the New Irish State by Angela Griffith, Marguerite Helmers and Róisín Kennedy (eds.) is published by Irish Academic Press.

From the March 2019 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home