From the December 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

According to the critic Joseph Warton, writing in 1756, no higher praise could be given to Dryden’s ‘Song for St Cecilia’s Day’ than to compare it to a painting. ‘This is so complete and engaging a history-piece,’ Warton commented, that I knew a person of taste who was resolved to have it executed, if an artist could have been found, on one side of his saloon. In which case, said he, the painter has nothing to do, but to substitute colours for words, the design being finished to his hands.

In the eyes of Warton’s tasteful friend, Dryden’s stanzas aren’t merely like a visual work of art, reminiscent, in their structure or detail, of painterly mark-making: they are a painting, a ‘finished’ ‘history-piece’, ready to be transposed on to his saloon wall by a straightforward process of swapping words for colours. Dryden’s poem is admirable, ‘complete and engaging’, because it’s capable of being, or seeming to be, what it isn’t. It becomes an exemplary instance of poetic art to the degree that it can be collapsed, by an effort of the imagination, into the sister art it resembles.

Lady Macbeth Walking in Her Sleep (detail; c. 1784), Henry Fuseli. Musée du Louvre, Paris. © RMN- Grand Palais (musée du Louvre)/Hervé Lewandowski

The 18th century in Britain, as Jean Hagstrum has argued, ‘saw the culmination of the literary man’s increasing sophistication in the visual arts’. Contemporary poets adopted a pictorial vocabulary, alluding to the work of celebrated Renaissance painters; critics urged the Horatian maxim of ut pictura poesis (‘as is painting, so is poetry’), instructing writers to learn from the superior procedures of the visual arts how to hold a mirror up to nature.

The relationship in the other direction – what painting could learn from poetry, what subjects and scenes from literature it might adopt – developed along different critical lines. The embrace of literature by the visual arts in the second half of the century was in large part a response to changing circumstances in the art world. From the 1760s, history painting, long overshadowed by portraiture and the fashionable genre of landscape art, began to receive institutional encouragement from the Royal Academy and its exhibitions. British artists who hoped to distinguish themselves as history painters, practitioners of the most exalted genre, were aware of lacking an established native tradition on which to model their work, of the kind their Italian or French contemporaries could boast. As a redress, they turned for inspiration to a different sphere of art, one that was a source of national pride. English literature, the revered works of Shakespeare in particular, seemed to promise both a storehouse of new subjects (ones untouched by previous artists) and a shortcut to being taken seriously: in Shakespeare, the critically admired genius who had refused to play by the rules, they found cultural legitimacy as well as a template for taking imaginative risks. The publisher John Boydell’s Shakespeare Gallery (1789–1805), which housed paintings commissioned to illustrate a luxurious new edition of the Bard’s works, combined commercial hopes – the growth of an international market for British engravings – with national aesthetic ones. ‘The abilities of our best Artists are chiefly employed in painting Portraits of those, who, in less than half a century, will be lost in oblivion,’ Boydell noted severely in his catalogue for the gallery. To ‘establish an English School of Historical Painting’ and to ‘advance that Art towards maturity’, was, he wrote, ‘the great object of the present design.’

The artist at the vanguard of the literary turn in the later 18th century was Henry Fuseli (1741–1825). Though born and educated in Zurich, Fuseli had been taught to read and admire English literature, Shakespeare and Milton in particular (one of his university tutors had translated Milton into German; he himself had attempted a translation of Macbeth). As a painter, he sought to reveal fundamental similarities between the ways the sister arts interpreted the world. Since writers and artists both, at their best, viewed ‘nature through the medium of a fine imagination’, as he argued in a piece for the Analytical Review in 1788, what they produced might differ locally or technically, in ‘machinery’ and quality of materials, but not in essentials. ‘They will have a general resemblance in the ideal.’

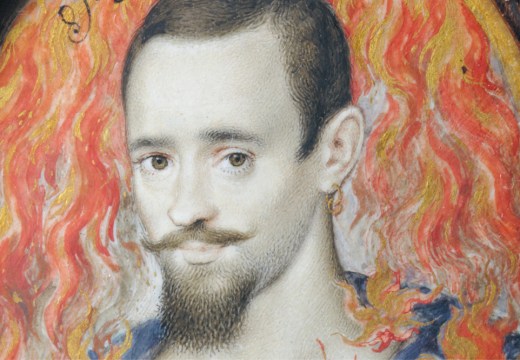

The Fire-King (1801–10), Henry Fuseli. Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The first work Fuseli exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1772 was a drawing of Cardinal Beaufort’s deathbed scene in Shakespeare’s Henry VI Part 2, a sharply lit composition that drew the eye to the cardinal’s venomous, contorted face. In 1777, he sketched a Michelangelo-style decorative schema for a projected ‘Shakespeare Chapel’, whose walls he envisioned painted with key moments from The Tempest, Twelfth Night, King Lear and Macbeth. Shakespeare, in company with Milton, whose Paradise Lost he honoured in a cycle of 40 pictures exhibited in 1799–1800, supplied him with the necessary materials to fashion himself as an artist of the high-cultural sublime. Contemporary Gothic literature, of which he was a sophisticated reader (he invented a fake Provençal literary source for his Percival delivering Belisane from the Enchantment of Urma (1783), riffing on the fashionable trick of making up ancient origins for narratives), connected him to the popular market for sensational works of the imagination. Audiences would have known just how to read The Fire King (1801–10), his depiction of a macabre Crusades ballad by Walter Scott: the action takes place at the bottom of a darkened set of steps, as if in a castle interior; the demonic Fire King, with his wild grey hair and fixed, staring eyes, seems a nod to the enigmatic phantoms of Ossian.

Fuseli’s attraction to sensational material, the supernatural in particular, was sanctioned by a growing critical consensus around the imaginative uses of superstition. Those who sought to depict ‘unknown visionary beings’ – witches, ghosts, fairies and the like – required a bold, unrestrained faculty of invention, the critic William Duff suggested in 1767: being able to picture the invisible, in words or paint, counted as a ‘most pregnant proof of truly ORIGINAL GENIUS’. It was the kind of genius that showed itself in stepping over the ‘brink that separates the real from the possible’, as Fuseli put it in a Royal Academy lecture. There were, nonetheless, rules, even in a creative realm that didn’t seem to harbour them. For supernatural fictions to be believable, ‘plausible to our senses’, Fuseli argued, they needed to some degree to be anchored in the known, in the shapes of nature or in pre-existing traditional tales. Representing witches ‘holding their sabbath’ ‘on the blasted heath’, and ghosts ‘whispering a bloody secret […] at the midnight hour’, the Shakespeare critic Elizabeth Montagu wrote, observed a kind of ‘propriety of place and action’: it located them in beliefs that were already popularly held.

A Mandrake: A Charm (c. 1785), Henry Fuseli. Yale Center for British Art, New Haven

Fuseli turned to literary tradition to locate his depictions of the marvellous. In The Mandrake: A Charm (c. 1785), a dimly lit, huddled composition, a muscular, androgynous witch is shown crouching to dig up a mandrake root, traditionally associated in folklore with devilish magic: she (or he) is a version of the sinister third witch in Ben Jonson’s ‘The Witches’ Song’, reproduced for 18th-century audiences by Thomas Percy in his anthology Reliques of Ancient English Poetry (1765). ‘I last night lay all alone / O’ the ground, to heare the mandrake grone; / And pluckt him up, though he grew full low,’ the witch reports to her coven. Robin Goodfellow (Puck) (1787–90), painted for Boydell’s Gallery, alludes only incidentally to Shakespeare’s Puck in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, instead drawing on another 17th-century Percy ballad, ‘The Merry Pranks of Robin Goodfellow’. The drunken horseman at the bottom of the picture, his shocked open mouth the same bright red as his billowing cloak, is unaware that the beast he’s struggling to control is Robin in one of his mischievous guises, bent on whirling him (and his fellow night-wanderers) off course:

Sometimes I meete them like a man;

Sometimes, an ox, sometimes, a hound;

And to a horse I turn me can;

To trip and trot about them round.

But if, to ride,

My backe they stride,

More swift than wind away I go.

Robin exists in two places at once: transfigured into an animal in one corner of the picture, while, in his native shape, whirling gracefully above his moonlit kingdom, larger than life, in the painting’s centre. His magic is registered by the composition’s own impossibility, the way it freezes successive actions or modes of being into simultaneity.

Robin Goodfellow (Puck) (1787–90), Henry Fuseli. Museum zu Allerheiligen, Schaffhausen. Photo: Jürg Fausch, Schaffhausen

Ut pictura poesis, drawing an analogy between two things, is an admission that they aren’t the same. (‘We don’t expect systems of representation to replace one another,’ T.J. Clark has observed.) During the 18th century, even those who pressed the relationship between the sister arts acknowledged that there were significant differences between them. Chief among these was the question of temporality: painting was an art of the moment, its meaning projected immediately and all at once (tout à coup); poetry was an art of succession, releasing its meaning as a narrative in time, capable of showing bodies moving through space. Lessing’s distinction in Laocoön (1766) set clear limits to the kinds of representation painting could achieve: ‘If painting, by virtue of its symbols or means of imitation, which it can combine in space only, must renounce the element of time entirely, progressive actions, by the very fact that they are progressive, cannot be considered to belong among its subjects.’

Fuseli thought of limits as things to be transgressed. His cycle of Milton canvases, as Luisa Calè has shown, strung together key moments from Paradise Lost in a fragmented narrative, requiring viewers to ‘read’ them as a single story by filling in the gaps imaginatively. In individual compositions, too, as in the strange doubleness of his Robin Goodfellow, he found inventive ways to depict or imply progression. Raphael, he argued in a lecture, was admirable for having pulled off ‘one of [invention’s] boldest flights’, the combination, by means of suggestion, of ‘two successive actions in one moment’. In his own art, he selected for depiction what he called the ‘middle moment’ in a narrative: ‘the moment of suspense’, the crisis, ‘big with the past and pregnant with the future’. ‘Suspense’, etymologically, relates to uncertainty, things hanging in the balance, a kind of freighted pause between past and future – Eve and Adam trying not to look back in The Dismission of Adam and Eve from Paradise (1796–99), their bodies twisting expressively between the world they’ve lost and whatever is to come next.

Scenes of foreshadowing, narrative cruxes that compress a glimpse of the future into their present, attracted Fuseli as economical solutions to the problem of temporality. In Dion and the Apparition (1768), one of his earliest history paintings, the dynamic Fury that Dion of Syracuse glimpses is both present and not, bearing narrative weight chiefly in relation to the alarming future it prophesies. Other compositions are shadowed by the past they imply. Lady Macbeth Seizing the Daggers (exhibited 1812), a treatment of one of Fuseli’s favourite subjects, the aftermath of Duncan’s murder in Act II, displays what the Earl of Shaftesbury had described as an artist’s power ‘to leave still in his Subject the Tracks or Footsteps of its Predecessor’. The daggers Macbeth clutches, red with blood in an otherwise monochromic composition, bear the traces of the king’s murder, while his frozen posture, reading somehow as both backwards- and forwards-moving, on the threshold of the darkened room, speaks to the moment of crisis the painting occupies.

Lady Macbeth Seizing the Daggers (c. 1812), Henry Fuseli. Tate, London

For those who sought to separate painting and poetry, to insist on fundamental differences between the way they operated, poetry, as an art of language, seemed to have a greater claim on the category of the sublime. Painting, able to capture, unmediated, the forms of nature and bring them before the eye, appealed merely to the visual sense, it was argued; poetry, with its reliance on arbitrary signs, the way it was suggestive and evocative rather than transparent, was capable of going beyond the merely visual to stimulate the imagination and intellect. When it came to depicting sublime, awe-inspiring things, painting’s very clarity was its enemy: ‘To see an object distinctly, and to perceive its bounds, is one and the same thing,’ Burke wrote in his Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1757). ‘To make anything very terrible, obscurity seems in general to be necessary.’

Fuseli agreed that clarity and detail in painting militated against sublimity. ‘It is not by the accumulation of infernal or magic machinery, distinctly seen, […] that Macbeth can be made an object of terror,’ he wrote, criticising the packed composition of Reynolds’ Macbeth and the Witches (1786). Enormity, the sublimely overwhelming, couldn’t be achieved by piling up props or emblems, the artist’s usual storehouse of significant bits and pieces (‘the axe, the wheel, saw-dust, and the blood-stained sheet’). Apparatus, by striving to be legible, was bound to ‘destroy terror’. His pictures, instead, sought to make painterly sublimity possible by being as suggestive – ambiguous, imponderable, if necessary illegible – as they could. In their composition, they tended towards the sparse (as in Lady Macbeth Seizing the Daggers, two ghostly figures in a dark room), or the disorientingly copious, as in Dion and the Apparition, where the jumbled classical debris in Dion’s chamber seems purposely to confound meaning.

The Night-Hag Visiting Lapland Witches (1796), Henry Fuseli. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

His figures, too, though designed to be recognisable as literary characters, were often physically ambiguous and indeterminate: muscle-bound to the point of being impossible, existing somewhere ‘between living flesh, sculpted stone and anatomically excavated corpse’, as Martin Myrone has written. The most nightmarish scenes he painted featured supernatural shapes that terrified because they refused to be seen clearly. In The Night-Hag Visiting Lapland Witches (1796), the ghastly visitation, Milton’s ‘hag’, is pale and amorphous, ringed by its own faint aura; the hulking witch in the foreground, squinting up at it, seems to echo a version of our own uncertainty. In The Three Witches (after 1783), Fuseli played with disorientating repeating effects, ranging together three figures who are both distinct and indistinct from each other, deliberately only half-rhyming. Their expressions are broadly the same, but not quite; the positioning of their crooked fingers on their chins alters a little each time; the light illuminates them unevenly; even the hair of their eyebrows sprouts in different directions.

When the subjects he chose veered too close to intelligibility, he used sublime mechanisms to make them strange. A disembodied ‘colossal head’ rises out of the dark bottom corner of Macbeth Consulting the Vision of the Armed Head (1793), wearing, in an embellishment of Shakespeare’s invention, Macbeth’s own features: across the diagonal of the picture, the protagonist, aghast, locks eyes with the impossibility of his double. Fuseli had, he wrote to the picture’s buyer, merely ‘endeavoured to supply what is deficient in the poetry’: ‘What, I would ask, would be a greater object of terror to you, if, some night on going home, you were to find yourself sitting at your own table?’

‘Füssli: the Realm of Dreams and the Fantastic’ is at the Musée Jacquemart-André Paris, until 23 January 2023.

From the December 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home