The Pre-Raphaelite painter Henry Wallis (1830–1916) received much critical acclaim during his own lifetime, yet he remains comparatively little known today. From 1854 to 1877 he exhibited at the Royal Academy almost every year, before becoming a leading member of the Old Water-Colour Society, where some of his works were praised for ‘their striking truth of local colour, their admirable keeping, and finished workmanship’. Wallis’s paintings were shown in Manchester, Liverpool, Dublin, Paris, Philadelphia and Melbourne. He was the friend and confidant of leading members of the art world, including William Morris and the critic F.G. Stephens. He was a close associate of Flinders Petrie, the Egyptologist and pioneer of modern archaeology. He was an expert adviser to public institutions. Yet, as a new biography and catalogue raisonné by Ronald Lessens and Dennis T. Lanigan points out, he has been entirely sidelined in the history of late 19th-century British art.

Today Wallis is best remembered for two successful paintings: The Death of Chatterton (1856), a meticulous representation of the suicide of the 18th-century poet Thomas Chatterton, and The Stonebreaker (c. 1857), a depiction of a working man slumped in the fading light, crushed as much by his poverty as his back-breaking labour. Both works show Wallis’s aptitude for colour: the rich auburn of Chatterton’s hair and the deep purple of his breeches are reprised in the autumnal tones and soft twilight depicted in The Stonebreaker, which John Ruskin judged ‘picture of the year; and but narrowly missing being a first-rate of any year’.

Today Wallis is best remembered for two successful paintings: The Death of Chatterton (1856), a meticulous representation of the suicide of the 18th-century poet Thomas Chatterton, and The Stonebreaker (c. 1857), a depiction of a working man slumped in the fading light, crushed as much by his poverty as his back-breaking labour. Both works show Wallis’s aptitude for colour: the rich auburn of Chatterton’s hair and the deep purple of his breeches are reprised in the autumnal tones and soft twilight depicted in The Stonebreaker, which John Ruskin judged ‘picture of the year; and but narrowly missing being a first-rate of any year’.

These works propelled Wallis into the heart of the British art scene. Yet from this point on it was generally accepted that he produced nothing, or so it was mistakenly believed until the 1970s, when, in a reversal of history’s usual gender narrative, Wallis’s story started to emerge through his association with Mary Ellen Meredith, the wife of author George Meredith (model for Chatterton), with whom he had a scandalous and ultimately unhappy affair.

Despite the authors’ best efforts, little is known about Wallis’s early life. He was born out of wedlock and when his mother married Andrew Wallis, a wealthy property owner, the family was able to support Henry’s artistic education, initially at the Royal Academy Schools and then at the atelier of Charles Gleyre in Paris. What Lessens and Lanigan lack in biographical detail they make up for in their evocation of the professional art world at that time, in particular what some perceived to be the ‘self-elected, self-governing, self-serving’ pomposity of the Royal Academy. Although Gleyre – who went on to teach Bazille, Sisley, Renoir and Monet – followed traditional academic principles, his studio had a less restrictive atmosphere.

Back in England, Wallis’s name began to appear in the correspondence and diaries of the Pre-Raphaelite circle, and he became close to Holman Hunt and William Bell Scott. In 1877 he attended the inaugural meeting of the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings, in which William Morris was a leading figure; he was honorary secretary of Morris’s committee to preserve the Basilica of St Mark in Venice. In contrast with the socialist principles of Morris, however, the authors conclude that Wallis was uncomfortable with socialism, ‘more anxious about the stock exchange than the awful conditions in which the poor lived’. Decrying the narrow hero worship of much contemporary art history, the authors instead offer a refreshingly balanced perspective on Wallis’s – often unheroic – character and views.

Dr Johnson at Cave’s, the Publisher (1854), Henry Wallis

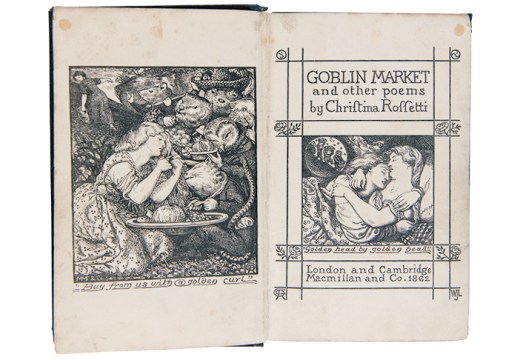

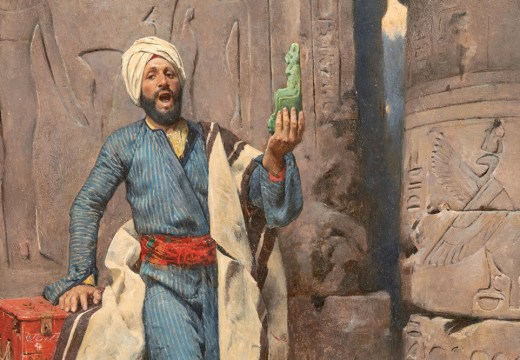

Wallis’s desire for historical accuracy is found throughout his paintings, from the impressively rendered textiles in a scene with Samuel Johnson that has echoes of Vermeer to the representation of a gondola in an Italian Renaissance scene, drawn from sketches sent by a friend in Venice. His talent for acute observation became especially clear from the mid 1870s onwards, when, coinciding with frequent trips to Italy and Egypt, he turned to watercolour painting. Armed with this portable medium, Wallis recorded scenes of everyday life, including the nascent archaeological excavations along the Nile. While it is not easy to agree with the authors that Wallis’s paintings of local life in Egypt are free of the Western gaze (see, for example, a depiction of Flinders Petrie admiring an archaeological find, surrounded by local workers who appear to be admiring Petrie), such works speak to Wallis’s first-hand experience of Egyptian material culture, and his intimate role within the archaeological community. As in London, Wallis knew the right people; he was even granted an audience with Heinrich Schliemann, the archaeologist who discovered Troy.

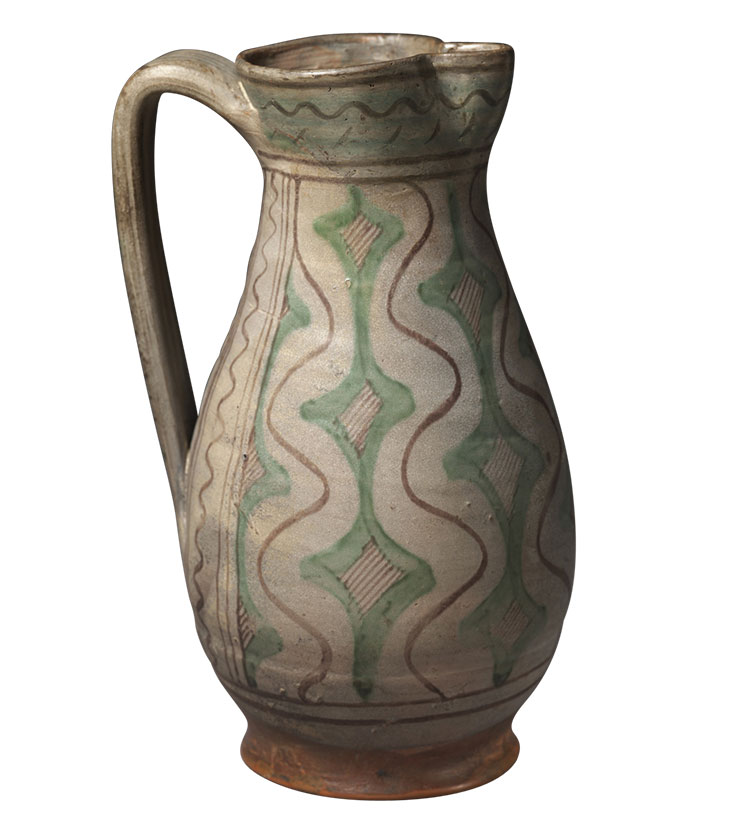

Wallis’s close study of historical objects led him to a second career as a collector, scholar and art dealer. His real passion was for Italian and Islamic ceramics – he published widely on the subjects – but he also collected oriental rugs, manuscripts, metalwork, glassware and fine art. From the 1880s his expertise saw him act as an intermediary in negotiating the purchase of certain objects for the South Kensington Museum (now the V&A) and the British Museum; he also donated – and occasionally sold – objects from his own collection. It is thanks to Wallis that these museums formed large parts of their collections of maiolica and Islamic pottery, which visitors can still see today.

Hispano-Moresque plate (c. 1400–50), Spanish. Courtesy Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Given Wallis’s profile during his lifetime, it is interesting to speculate on his descent into obscurity. George Meredith went to some lengths to expunge all memory of Wallis’s relationship with Mary Ellen, while no doubt his move from oil to watercolour limited his artistic appeal. Yet a more convincing argument may be that Wallis’s imperialist antiquarianism and social conservatism have prevented his work from resonating with the modern world. His instincts seem to have been for paternalistic safeguarding of the past rather than for historic preservation as an act of radical social egalitarianism, as the founders of the SPAB intended. As one reviewer wrote of Wallis’s Herodotus at the Scribe’s Bazaar, Memphis (1887), he possessed great technical skill ‘but a total incapacity for grappling with the dramatic, or even the human, element in the subject attempted’.

At a time when we are conscious of the collecting histories of our national institutions, and initiatives to decolonise museums are gathering pace, this book offers valuable insight into a man whose life and work are part of a complex legacy. Lessens and Lanigan have paved the way for renewed interest in Wallis as both a painter and collector/connoisseur.

Jug (late 14th/early 15th century), probably Tuscany. Courtesy Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Henry Wallis (1830–1916): From Pre-Raphaelite Painter to Collector/Connoisseur by Ronald Lessens and Dennis T. Lanigan is published by ACC Art Books.

From the March 2020 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home