In the 15th and 16th centuries, a tradition emerged within Renaissance painting of creating three-dimensional portraits that concealed the sitter’s likeness from immediate view. This was achieved through complex physical barriers: portraits were hidden within boxes, shrouded by sliding or hinging covers, or placed on the object’s reverse. Externally, they were decorated with puzzles and riddles that, upon decoding, hinted towards the identity of the elusive subject. For the first time, this unusual practice is being explored in a major exhibition at the Met, shedding light on how and why these portraits were created (2 April–7 July). Highlights include expertly crafted examples by artists such as Titian and Lucas Cranach, as well as the reunification of several portraits with their elaborate covers, long separated by both time and distance. Find out more on the Met’s website.

Preview below | View Apollo’s Art Diary

Portrait of Margarethe Vöhlin (1527), Bernhard Strigel. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Portrait of a Man (c. 1485), Hans Memling. Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid.

Still Life with a Jug of Flowers (verso of Portrait of a Man) (c. 1485), Hans Memling. Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid.

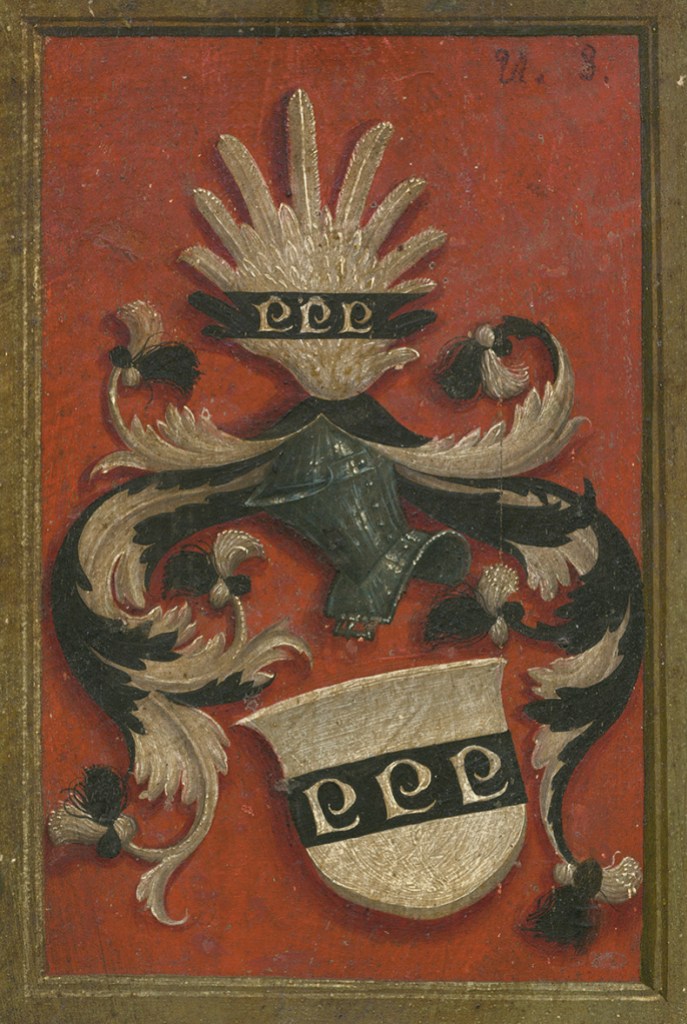

Coat of Arms (verso of Portrait of Margarethe Vöhlin) (1527), Bernhard Strigel. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home