From the December 2020 issue of Apollo. Preview the current issue and subscribe here.

From the December 2020 issue of Apollo. Preview the current issue and subscribe here.

In the opening pages of this book, Suzanne Marchand states that she is ‘not deeply concerned with porcelain as a “thing”’ – a rather surprising comment to find in a work with this title. Art historians, collectors and lovers of ceramics will perhaps be disappointed to learn that the book rehashes familiar stories and tropes, without significantly expanding our understanding of porcelain production, its cultural importance or its materiality. Instead, Marchand has chosen to focus on what the inner workings of a luxury industry can tell us about German economic history and the changing nature of work and consumption. In a volume of ambitious scope, she covers more than 300 years of porcelain making in central Europe. We hear the well-known story of princes locking up alchemists and bribing workers, all to discover the secrets of making porcelain, the so-called ‘Arcanum’, and claim the recipe for their own. Marchand maintains that these princes were motivated by a desire to display their grandeur, or what she terms their Glanz.

The book succeeds in demonstrating how European porcelain has changed over the years; from its role as aristocratic and princely objet d’art to a commodity bound up with the luxury-goods market, to a powerful symbol of the family, now found in the ordinary home. Marchand uses a remarkable and at times somewhat overwhelming number of archival sources, from worker wages to factory costs, price lists, sales catalogues, and so on. Ultimately, this is a business account of how porcelain was produced and how its consumption has evolved.

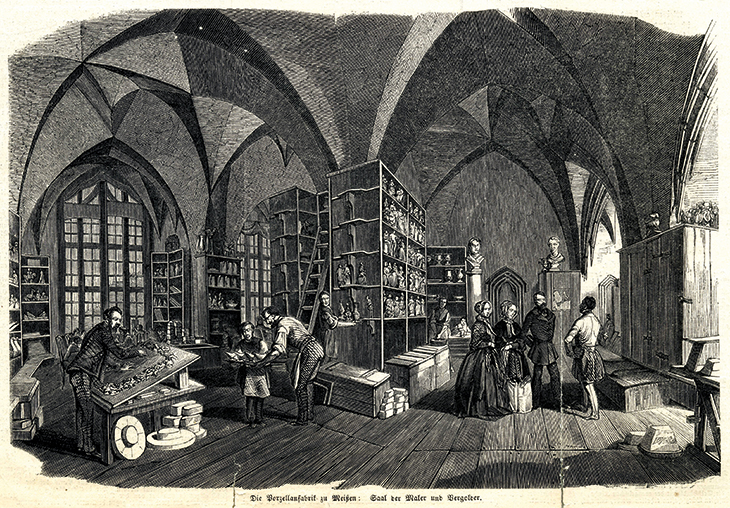

Illustration of the Meissen modelling studio in Albrechtsburg Castle, Meissen, just before the move to a dedicated factory in 1869. Photo: © Schlösserland Sachsen

Marchand begins by tracing the spread of the secret recipe across the German states. Early experiments in Dresden by the alchemists J.F. Böttger and Count von Tschirnhaus at the turn of the 18th century later led to the first discovery of ‘white gold’. The establishment of the Meissen porcelain factory soon followed, patronised by Augustus the Strong, Elector of Saxony (the book does not mention that Augustus suffered what he himself called a maladie de porcelaine, an addiction to collecting it). Marchand considers a wide range of factories: Höchst, Neudeck (predecessor to Nymphenburg) and Ludwigsburg, as well as those in the lesser known regions, including what is now the German federal state of Thuringia. Yet managing to produce porcelain was only half the battle, and did not always lead to economic survival. Profit margins were low or non-existent, with several factories all vying for the same buyers. As the demand for porcelain making grew, factories elsewhere provided Germany with direct competition, especially Sèvres in France, and British factories such as Chelsea and Wedgwood. Marchand presents Josiah Wedgwood as a successful salesman and designer who understood the fast-changing pace of the late 18th century, though in describing him as a ‘hustler’ I would argue she goes a step too far. Such a label negates not only his significant role in the Industrial Enlightenment but also his innovative approach to the production and marketing of his wares. At times, the writing is somewhat anachronistic – a comparison of the infamous Sèvres porcelain end-of-year Christmas sales for the court at Versailles to ‘Black Friday’ seems a stretch.

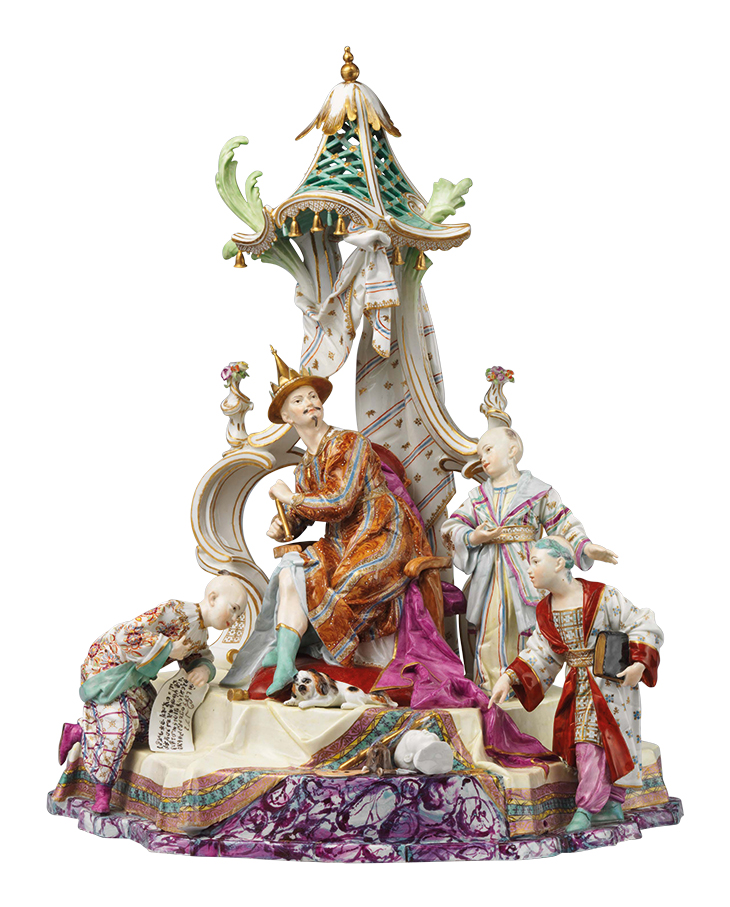

Audience of the Chinese Emperor (c. 1766), Höchst manufactory, Frankfurt. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Marchand paints a colourful picture of the day-to-day life of porcelain factories, from the sense of community to embedded hierarchies, hazardous and life-threatening materials and the intensive labour processes involved. Often it took more than 60 hours to grind ingredients into fine powders for the glazes, not to mention the time, risk and waste involved as pieces entered the incredibly hot kiln, over and over again. We gain a real insight into the lives of these workers: one painter at Fürstenberg managed to paint more than 200 pieces in just 17 days. But at the same factory workers indulged in drinking schnapps and at one stage even took over the kiln illegally to roast chicory to make themselves ‘Prussian’ coffee.

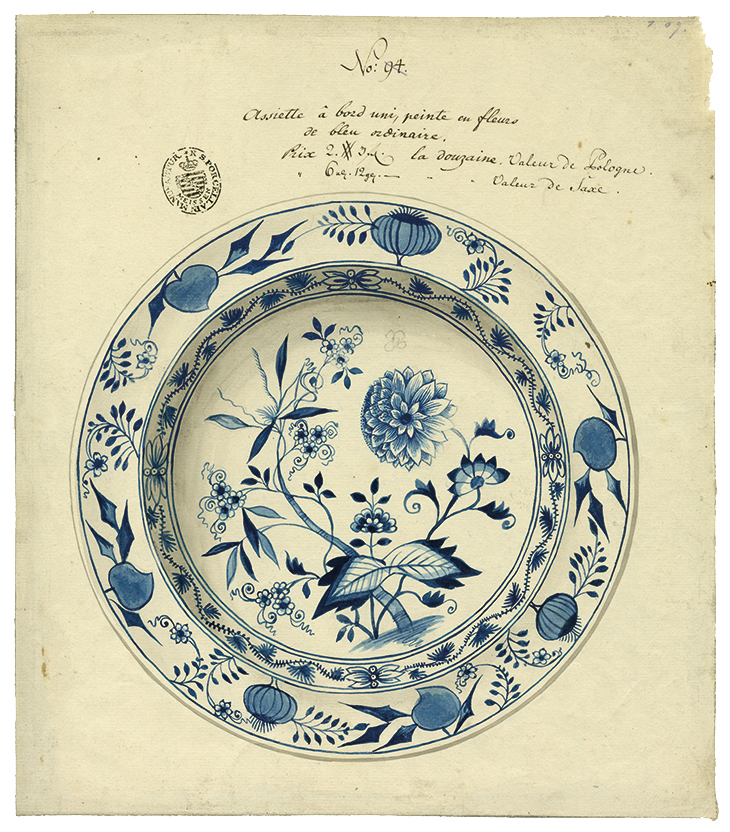

A late 18th-century drawing of the ‘Blue Onion’ pattern, first designed at Meissen in 1738. Staatliche Porzellan-Manufaktur, Meissen. Photo: Staatliche Porzellan-Manufaktur Meissen GmbH, Unternehmensarchiv

Throughout, Marchand asks what porcelain can tell us about life, society, and patterns of consumption during the modern period. Factories were often forced to adjust to changing cultural, political and economic conditions, ranging from the Seven Years War to various revolutions and the rising threat of industrialisation. Soon, the nature of patronage shifted as the rising middle classes began to guide production. Charting the steady decline of worker pay throughout the 19th century, Marchand shows how, as prices became more competitive, women, who were more cost-effective, were brought in to the workforce. Employees of the Royal Porcelain Factory (Königliche Porzellan-Manufaktur) in Berlin petitioned for better fixed wages and more secure working conditions, and Meissen saw similar protests. By 1869 porcelain workers had founded the Workers’ Association for Porcelain, Glass, and Related Trades – rightly so, as new uses for ceramics came into being, with a focus on utilitarian manufacture, for example, providing insulation for telegraph links between Berlin and Frankfurt. In fact, the number of porcelain workers in German-speaking lands would only continue to rise, increasing from 23,094 in 1882 to 51,785 in 1907. Of course, this would change rapidly once again with the world wars as demand changed and the ceramics industry embraced mass-production.

Salesmen from the porcelain manufactory Bareuther & Co. at the Leipzig fair, 1920s. Photo: Georg Pahl/Bundesarchiv, Bild 102–13204

By the 1930s, the Nazi regime saw white porcelain as a ‘prestigious “German” art form’, with Hitler favouring the Nymphenburg factory (despite the fact that it was now run by the Bäuml family, who were Jewish, as defined by Nazi racial laws). This is a fascinating discussion that suggests a number of areas ripe for more research, especially the tensions between ‘good design’ and what Marchand terms ‘fascist classicism’ under Hitler’s reign. As the book draws to a speedy close, jumping from the 1960s to the present day, we are left with uncertainty about the future survival of the German porcelain industry. Between 2006 and 2014 alone almost 200 porcelain firms closed their doors. And, no doubt, recent events will have had further impact on the remaining factories.

Porcelain: A History from the Heart of Europe by Suzanne L. Marchard is published by Princeton University Press.

From the December 2020 issue of Apollo. Preview the current issue and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home