‘When somebody asks what the stunning highlights of the collection are, we say, well, actually, nothing – it’s all everyday stuff.’ While it’s a quotably disarming thing for a museum director to say, Nick Merriman, the chief executive of the Horniman Museum and Gardens in south-east London, is also making a serious point about the new World Gallery, which opened at the end of June and displays some 3,000 objects from the museum’s important collection of ethnographic artefacts. And while giving a tour of the new gallery – which is still being installed during my visit at the end of May – Sarah Byrne, the deputy keeper of anthropology, makes the same observation about what the displays are trying to convey: ‘The objects are important, but it’s really about the social relationships behind them.’

When I speak to Merriman, he has been in post at the museum for just over a month, taking over from Janet Vitmayer, who led the museum for 20 years and transformed the institution through a series of building projects and refurbishments, of which the World Gallery is the last stage. Despite its new director’s disclaimer, the Horniman is a thoroughly unusual institution. As Merriman puts it, ‘on the face of it the collections can seem a little quirky’. One of the most striking features of the museum is its site in Forest Hill, one of the hilliest parts of London. Some of the best views across the city can be enjoyed from within the Horniman’s 16.5-acre site, but the views it provides also emphasise that the museum is an institution that sets itself apart. The museum is both a hugely popular local institution and something of a well-kept secret in the city. Merriman – who sounds as if he has spent the time since his appointment in November taking soundings – says that the phrases that he has encountered the most in relation to the museum are ‘love – the museum is much-loved’ and ‘Where’s that, then?’ He clearly intends to start bridging the gap between those reactions.

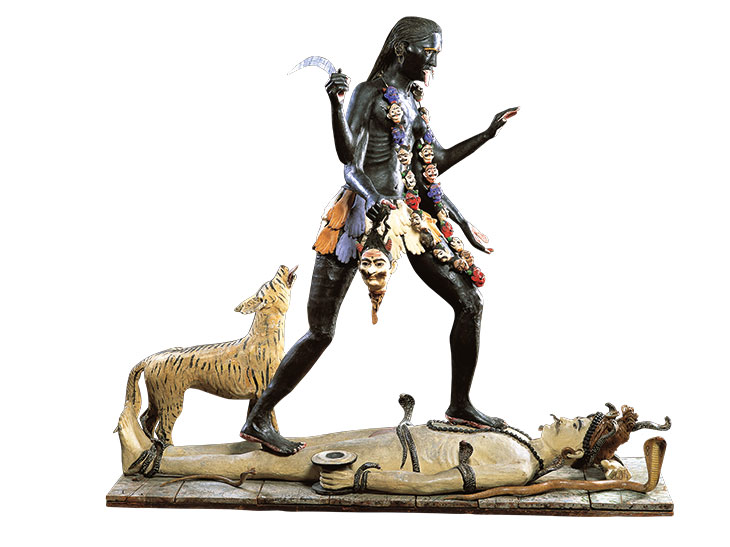

Figure of Kali dancing on Shiva and accompanied by a striped wild animal (c. 1895), Calcutta, India. Horniman Museum and Gardens, London

Frederick Horniman (1835–1906) was a Liberal MP and tea merchant, who came from a Quaker family. His father, John Horniman, established a tea business on the Isle of Wight and made his fortune by inventing a method for keeping tea fresh by selling it in sealed packets. By the end of the 19th century, the Horniman Tea Company was one of the largest in the world. Frederick Horniman had followed his father into the business and during the course of his extensive travels in India and Ceylon and, later, non tea-growing countries, he formed a collection of natural history specimens and arts from all over the world. As his house in Forest Hill began to fill with items from his travels, he moved up the road into another residence and, in 1890, opened up his former home to the public on selected days of the week, and free of charge.

As the collection began to outgrow its home a second time, Horniman decided to build a bigger public museum – with the intention of bringing ‘the world to Forest Hill’ – and commissioned the Arts and Crafts architect Charles Harrison Townsend to design it. Like the Horniman Museum, Townsend’s other notable buildings in London – the Bishopsgate Institute and the Whitechapel Gallery – were commissioned by progressively minded philanthropists and social reformers and built in unfashionable and, in the case of the other two institutions, poor parts of the city. The Horniman’s architecture displays Townsend’s fondness for Romanesque arches and rounded forms – the latter particularly evident in the clock tower by what used to be the main entrance – and the façade bears Robert Anning Bell’s enormous mural, Humanity in the House of Circumstance. Horniman decided to present his new museum, which opened in 1901 (the same year as the Whitechapel Gallery) to the London County Council (LCC), dedicating it to ‘the public for ever as a free museum for their recreation and enjoyment’. Only 10 years later, Townsend designed an extension for a library and lecture theatre, funded by Horniman’s son Emslie. Much more recently, in 2002, the museum added a new building containing more gallery space, a café and a shop. One of the most characterful additions in the intervening period is the conservatory that stands in the grounds. It was originally constructed in 1894 for the Horniman family home in Croydon, where it stood in a state of disrepair until it was moved and rebuilt at the museum in 1989.

Taxidermy mount of a 19th-century walrus (Odobenus rosmarus), from Hudson Bay, Canada, in the natural history gallery of the Horniman Museum and Gardens, London.

Another peculiar aspect of the Horniman is its funding and governance. Until 1986, the museum was run by London’s municipal government, first the LCC and then its successor, the Greater London Council. After the latter was abolished, the museum became an independent charitable trust. Although the Horniman is not one of the UK’s national museums, like them it is overseen (‘sponsored’) by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS); unlike them, it is also able to apply to the Arts Council – and has secured a £3.8 million grant over the four years from 2018–22. As Merriman puts it, ‘Increasingly, the Horniman is becoming not just a museum and garden, but also a centre where different types of arts are integrated. […] I think we’re a good example of the way in which major museums are morphing from only focusing on collections, to becoming creative hubs for their local community.’

So what is so quirky about the collections? At the outset, Frederick Horniman’s museum was divided into two sections: Nature and Art. The present-day collection of some 350,000 objects is divided into more sections, but art is no longer one of the organising principles. Instead, the two largest galleries are devoted to natural history and anthropology; there is a world-class collection of musical instruments, which is particularly strong in woodwind and brass instruments, as well as harpsichords and spinets, an aquarium, and a butterfly house that on a weekend seems always to be full. Merriman says it’s easier to make sense of the Horniman if one approaches it as ‘the only museum in London that allows you to deal with the whole world in an integrated way. In other words, it’s a world museum of environment and human cultures.’ Or, to paraphrase Merriman’s paraphrase, Frederick Horniman’s vision has morphed into Nature and Culture. As Merriman puts it, ‘In our minds and our programming [the collections] are connected, but we probably have to do more work to make that more visible to our visitors.’ He explains, for instance, how the collection of musical instruments can play its part. As well as being important in its own right, increasingly, the museum is ‘linking that to live performances of world music and of music from different traditions [of people who] live in London’.

Rectangular brass plaque depicting Agban, the Ezomo (Deputy Commander in Chief of the Benin army) (c. 1578), Edo, Benin City. Horniman Museum and Gardens, London

Nor does the museum shy away from making connections between some of its most controversial artefacts and less contentious ones. Frederick Horniman was an early purchaser of Benin artefacts and the museum has a number of bronzes. The examples in the ‘African encounters’ section of the World Gallery are accompanied by a label that explains the British expeditionary force’s invasion of the kingdom and looting of the royal palace. Downstairs in the music gallery, two bronzes are displayed – a plaque depicting Ekpenede, a commander-in-chief of the Benin army in the 16th century, followed by the figure of a miniature trumpeter, and a second of another commander called Agban with a four-sided bell. In the displays – as far as the labels are concerned, that is – the artistry of these objects takes a back seat to the story of where they came from, and to making connections to more everyday aspects of life. The labels for the bronzes in the music gallery suggest visitors seek out the instruments that are most closely related to the ones on the plaque.

Blanket with totemic designs (c. 1840–1900), Tlingit, Northwest Coast. Horniman Museum and Gardens, London

The World Gallery is located in the refurbished South Hall of the museum. Divided into a series of ‘encounters’ with Africa, the Americas, Asia, Oceania, and Europe, the displays have been designed by Ralph Appelbaum Associates, whose most notable ethnographic project is the redisplay of the Weltmuseum in Vienna. Here, as there, the cases are visually attractive and feature dense arrangements of objects. But at the Horniman there is a much greater emphasis on the connections that can be made to modern-day communities all over the world, and on the continuing importance of anthropological fieldwork, which the museum has been engaged in since the early 20th century. (In the autumn, the Horniman will launch a joint masters degree in anthropology and museum practice with Goldsmiths University.)

Kulap female memorial figure (late 19th century), Punam, New Ireland, Papua New Guinea. Horniman Museum and Gardens, London

‘All ethnographic museums in the West,’ Merriman explains, ‘that have collections from the 19th century, have that legacy of colonialism to deal with and they’ve dealt with it in different ways. […] What Horniman was interested in, and I think this may stem from his Quaker background, was, I think, much less in demonstrating the superiority of the West, but in showing the common humanity, the different cultural responses to common human issues.’ The everydayness of elements of the displays may or may not be related to Frederick Horniman’s founding intentions, but it is undeniably present in the displays I can see around me – and the museum is certainly interested in presenting them in what Merriman calls ‘a colonial, or postcolonial context’.

One of the World Gallery’s most interesting aspects is its presentation of European cultures – and not just in a folkloric sense. In the ‘European encounters’ section, for example, there is an intriguing display of straw goats from Sweden (a Christmas tradition) and a table set up with all the elements of a summer crayfish party. As Sarah Byrne says, ‘Sweden isn’t what you expect, but it’s a really interesting case in point of what anthropology museums should be doing.’

Swedish Christmas goat (Julbok) (20th century), Sweden. Horniman Museum and Gardens, London

All the same, during my visit and in any discussion of the Horniman and its mission, there’s an elephant in the room – or a walrus in the natural history museum. What the museum is best known for are its gloriously unreconstructed natural displays, in which the taxidermied animals have enchanted and horrified generations of children – and adults, too. From a wall that shows the bottled central nervous systems of the frog, pigeon, rat, cat and monkey, to a barn owl arranged in the act of taking flight, it’s one of the most striking displays of any museum in London. It is, however, incredibly old-fashioned and Merriman’s biggest challenge is to update the galleries without upsetting an audience (the writer of this piece included) who are attached to some of the individual cases.

Although the anthropological collections may not have a single pre-eminent exhibit, the superstar of the natural history galleries, and the semi-official mascot of the museum, is the famous Horniman Walrus, which sits on its artificial ice-floe in the centre of the North Hall. First seen in London in the Colonial and Indian Exhibition of 1886, the walrus’s most notable feature is its overstuffing, which created a comical lack of wrinkles and was carried out by a taxidermist who had never seen the real thing. Why does Merriman think the walrus, which is to the Horniman what the Mona Lisa is to the Louvre, so iconic? ‘For one thing,’ he explains, ‘it’s very big. Some of these things are very simple – children really remember it because it’s so big and they don’t see a walrus anywhere else. And unlike many natural history museums or galleries, the Horniman doesn’t have any other really large animals, so it’s the biggest one.’ As for the future, he continues, ‘I’m thinking of calling my 10-year master plan Don’t Mess with the Walrus, because that’s the one thing everyone has said to me.’

The World Gallery at the Horniman Museum and Gardens, London, opened on 29 June.

From the July/August 2018 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home