In the chilly New York winter of 1947, a little-known French photographer was given his first solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. His name was Henri Cartier-Bresson (1908–2004). The same year he and some photographer friends founded Magnum. Seeing themselves as artist-photojournalists they encouraged a higher quality in their trade. Early the next year Cartier-Bresson set out for newly independent India, camera in hand. Unwittingly, he found himself in position to cover one of the major world events of the 20th century: the last days of Mahatma Gandhi and then the funeral, cremation and scattering of his ashes. As that tragedy unfolded, Cartier-Bresson was catapulted into stardom.

This summer, as part of Magnum’s 70th anniversary celebrations across New York, the Rubin Museum gives Cartier-Bresson a solo show that fills its fifth floor. About half of the 70 black and white photographs in the show recount how Cartier-Bresson brought the visual story of Gandhi’s death to the world.

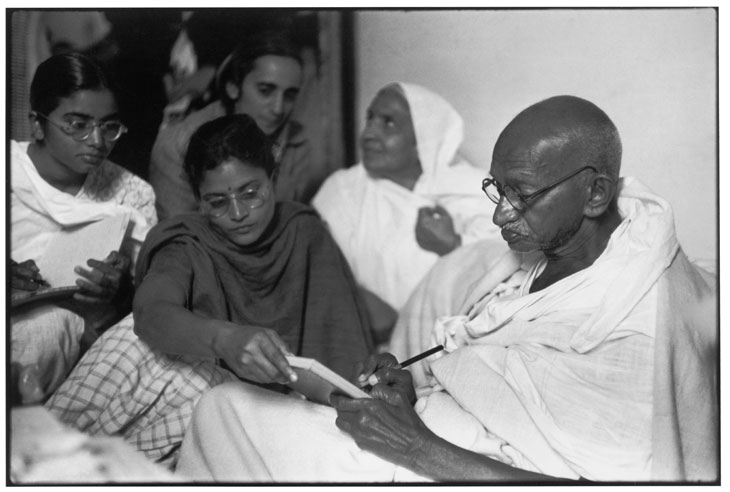

Gandhi dictates a message, just after breaking his fast Birla House, Delhi, India (1948), Henri Cartier-Bresson. © Henri Cartier-Bresson/Magnum Photos

Cartier-Bresson had gone to India with new enthusiasm, new purpose, and new equipment. Magnum’s small band of founders were unusual in being a co-operative of rigorously selected members who kept the copyright of their photographs, rather than lose it to the publication that used them. Cartier-Bresson would later write that ‘with Magnum was born the necessity for telling a story’. Before he departed, his co-founder Robert Capa advised him to be less of a ‘surrealist photographer’ and more of a ‘photojournalist…Get moving!’ The members carved up the world between them to explore it with their cameras – in particular the new small Leica that used more light-sensitive film and was quick and quiet to use.

Cartier-Bresson was assigned to cover India and the Far East. He and his Javanese poet-dancer wife, Ratna Mohini, landed in Mumbai just a few months after India’s independence, and made their way to the capital, Delhi. This is where the Rubin show begins. Moving from image to image, and then to the exhibition cases which display those same images printed in copies of Life, Heute, Illustrated, Harper’s Bazaar and other magazines, it is intriguing to see how he jumped right into the heart of Indian politics. Cartier-Bresson went to meet Gandhi in mid January 1948. His photographs captured the Mahatma (Great Soul) taking his first food after a fast in the name of peace, and later controversially visiting a Muslim shrine in Delhi to show sympathy for the Muslim Indians. Then, at 5.17pm on 30 January, just 90 minutes after Cartier-Bresson had last seen Gandhi, the Hindu nationalist Nathuram Godse – who scorned that very sympathy – assassinated him.

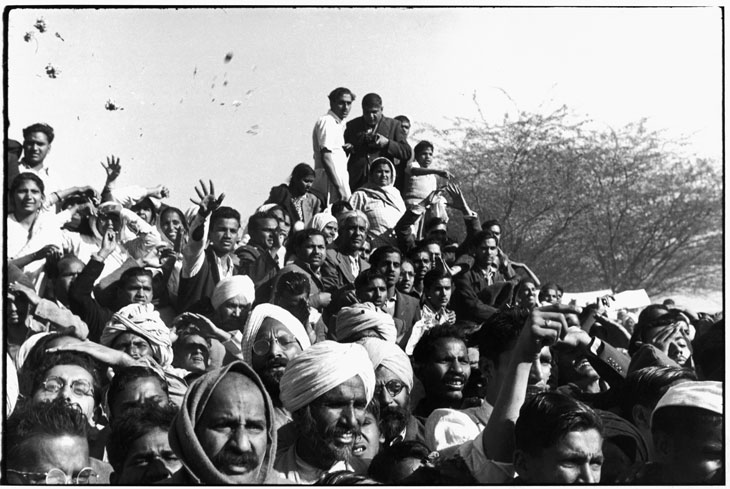

Crowds wait for Gandhi’s funeral cortege to pass by on its way to the Yamuna river, Delhi, India (1948), Henri Cartier-Bresson. © Henri Cartier-Bresson/Magnum Photos

The news sent Cartier-Bresson racing back to document the aftermath with his unobtrusive little Leica, which did not require flash. ‘We are bound to arrive as intruders,’ he later wrote. ‘It is essential, therefore, to approach the subject on tiptoe. It is no good jostling and elbowing.’ Later that night, and again without flash, he captured prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru announcing to the world: ‘The great light is extinguished.’ Mandela, King and others would take up Gandhi’s torch around the globe.

Cartier-Bresson also followed the days of mourning, then the funeral we now know so well from Richard Attenborough’s re-staging in his film Gandhi (1982), and the scattering of ashes into the sacred River Ganga at Allahabad. He captured the monumental size of the crowds as successfully as he did the pathos of individual mourners. His images show trees full of people who have clambered up above the crowds for a better view; one documents the almost unbearably intimate moment when Brij Kishen, Gandhi’s secretary, grieves beside the first flames of the pyre.

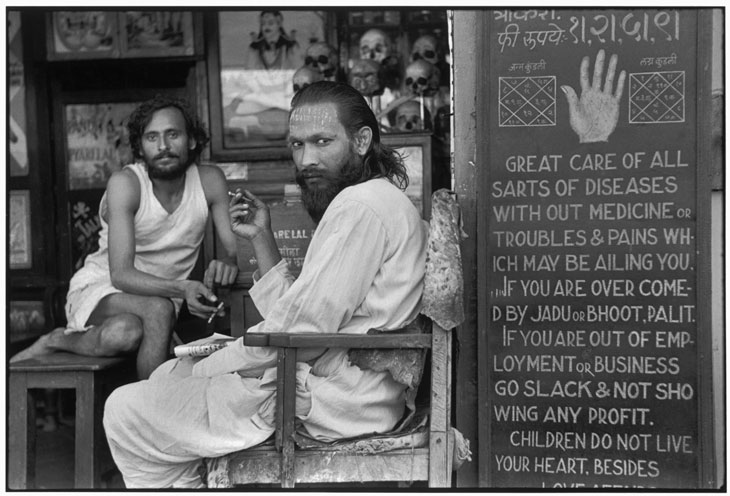

A astrologer’s shop in the mill workers’ quarter of Parel Bombay, Maharashtra, India (1947), Henri Cartier-Bresson.

The exhibition’s other photographs set the Gandhi story within the complex context of the contradictions and turmoil that followed India’s creation as an independent democracy. Images range from the well-known – Jawaharlal Nehru and the Mountbattens standing in front of Government House in Delhi – to quack doctors in back streets. They move from Muslim women praying on a hilltop in war-torn Kashmir to refugees exercising in a camp near Delhi housing 300,000 displaced people. Each remains as fresh today as when it was taken. Many capture society’s extremes with what Cartier-Bresson called the ‘decisive moment’ – a knowing glance between two people, a sari drying in the wind above some cows, a beggar with outstretched hand and pleading eyes, a maharani closing the clasp on her husband’s multi-string pearl necklace. These moments have a timeless and poignant global relevance today.

‘Henri Cartier-Bresson: India in Full Frame’ is at the Rubin Museum, New York, until 29 January 2018.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home